Most People Don’t Know How Librarians Select Collection Materials, So What Do They Think of Book Bans?: Book Censorship News, November 3, 2023

Book Riot and EveryLibrary have teamed up to execute a series of surveys exploring parental perceptions of libraries, and our first data sets were released at the end of September. These specifically explore the ways parents perceive public libraries. Looking at the results gives a sense of deep tension — 92% feel their children are safe at the public library, and most parents (66%) report not having their child borrow a book that made them uncomfortable. In the ongoing exploration of this data, let’s take a look at the cross tabs of one specific question that, while concerning, also showcases opportunity. What do the people who do not know how librarians select materials — that’s 53% of the responses — think about other topics related to contemporary book banning? I’ve isolated the respondents to the question in order to look at any potential trends among the rest of their responses. This is the second in a series diving deeper into the data. The first explored what else parents who believed librarians should be prosecuted for the materials in their collections thought.

The demographics of this subset of respondents are close to those of the overall sample. Most are white (70%), followed by Hispanic/Latinx (9%), Black (9%), Asian American (6%), Native (2%), and another race (3%). The vast majority, 85%, were between the ages of 27 and 58. This demographic tended to have less political party affiliation as republican or democrat than the overall sample (18% vs. 14%), and they also tended to choose independent affiliation more frequently (25% vs. 21%). Democrat and republican affiliations in this subset were nearly identical, but the “none” and “independent” affiliations differences are higher. Social media use mirrored the overall survey, with the most frequently used being Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and Twitter.

One noteworthy find in the basic information section, given at the end of the survey, was this: those within the subset of being unaware of how librarians selected materials for the collection were more likely than the full group to say book banning was not an issue important to them (45% of the subset vs. 36% of the full survey). In other words, people who don’t know how librarians select books are more likely not to care about book bans. In some ways, this makes sense. It might also be reflective of some overall messaging around book bans and the ways that this issue has been seeded within the democratic and republican parties, especially given that this subset is more likely to consider themselves independent or non-affiliated. We know this is not a partisan issue, but perhaps it is perceived as one.

This subset of users was only slightly less likely to have visited a public library in the last 12 months (91% to 93%), but they visited less frequently (on a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 indicating using the library all the time, the subset ranked a 5.7 and the overall survey a 6.6 — not significant, but noteworthy). They were also less likely to have a library card, with 88% saying they did and the overall survey indicating that 92% had a library card. Again, this data tracks: those who are unfamiliar with how libraries operate are likely those who visit less often and do not have a library card. But again, these differences are not significant ones.

Bigger differences emerged, though, when it came to whether or not these parents had children with library cards. Among the subset of respondents who did not know how librarians select materials for the collection, 52% stated their child had a public library card. In the full survey, 60% of parents said their child had a public library card. This stark difference appeared within another option in this question: 19% of these parents said their child did not have a public library card, while the full survey had this response only 14% of the time.

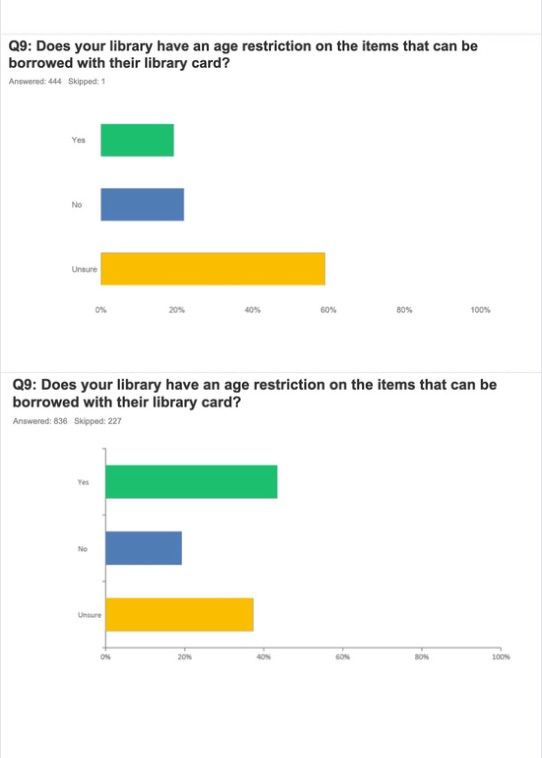

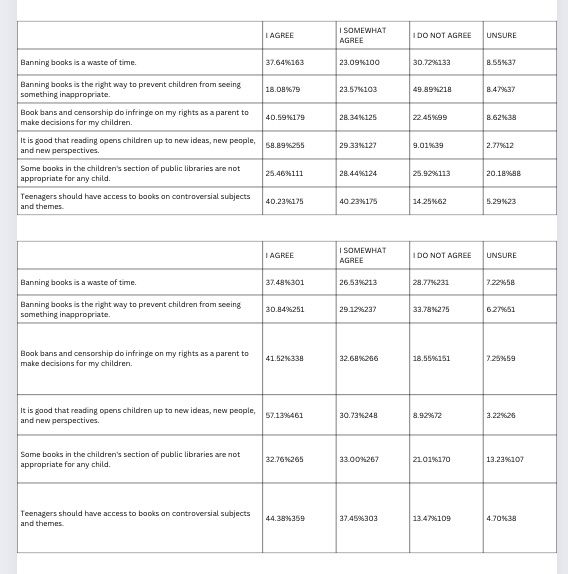

Unsurprisingly, a big difference emerged when asked whether or not parents knew if their library had any sort of age restrictions on children’s library cards. In the subset, 59% were unsure, while in the full survey, only 37% were unsure. For users who do not know how librarians select material, there is a great lack of understanding of what all their library does or does not do. The top image below represents the subset.

The answers continue to diverge, too. When asked whether or not a child had borrowed material that made them, the parent, uncomfortable, the subset had an 89% no response. The full panel had a 66% no response. This is a big difference. When asked the same question, but shifting from the parents’ discomfort to the child’s own discomfort with material borrowed, it’s even more stark: 90% of the subset had never had this experience, while in the full panel, it was only 67%.

Among the reasons may be that fewer children are checking out materials due to not having their own library card, restrictions on juvenile cards that the parents are not aware of, or, as to be discussed later on, perhaps the partisan positioning of book content plays a role in perception of materials in the library…though this also seems counterintuitive to the fact these parents are also unaware of how materials are selected for the library. It also counters the responses related to content in children’s materials and the differences therein between the subset and the overall panel.

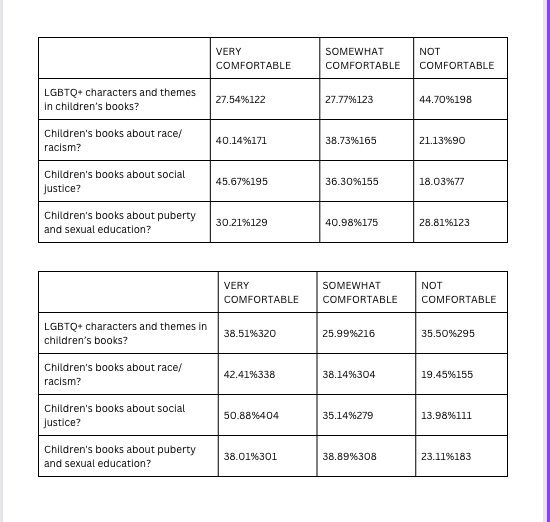

When it comes to LGBTQ+ books, the subset of parents is far less comfortable with those topics than the panel as a whole. The same findings repeat for books that explore topics of social justice and books on puberty and sexual education. They are slightly less comfortable with children’s books about race and racism, but not as significantly. Interestingly, more of the shift in responses fell into the middle column, “somewhat,” than over to not comfortable. Perhaps this again reflects some of the political affiliations within this group to be less decisive, outside mainstream, and/or, perhaps, less informed or willing to be informed on any of these topics (recall this is a subset who said they do not know how librarians select materials, which also suggests they are not interested or have not spent time learning this — those are value-neutral statements).

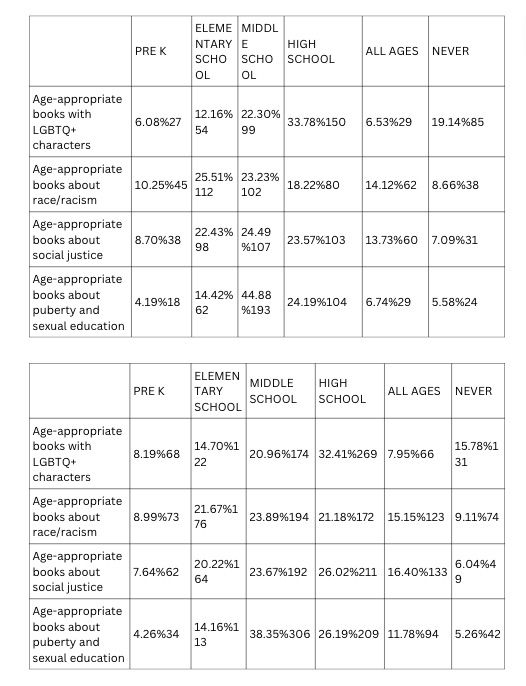

More of the subset believed children should never have access to books with LGBTQ+ characters than the overall survey. But they do not go that strongly on other topics; indeed, they are slightly more permissive about books covering race and racism and about equal when it comes to books on sex ed and puberty. Indeed, more of the responses from the subset fell into the middle school and high school categories rather than at earlier ages.

But if this group is more representative of non-partisan politics, it’s curious how the far-right talking points about LGBTQ+ books — and, by extension, people — are effective. That is something to be especially worried about. People who do not know how books get onto shelves in libraries are less likely to have library cards, more likely to never have experienced their child borrow material that made them or their child uncomfortable, and yet they’re more likely to say no one under 18 should ever have access to age-appropriate books with LGBTQ+ characters. That’s characters, not content.

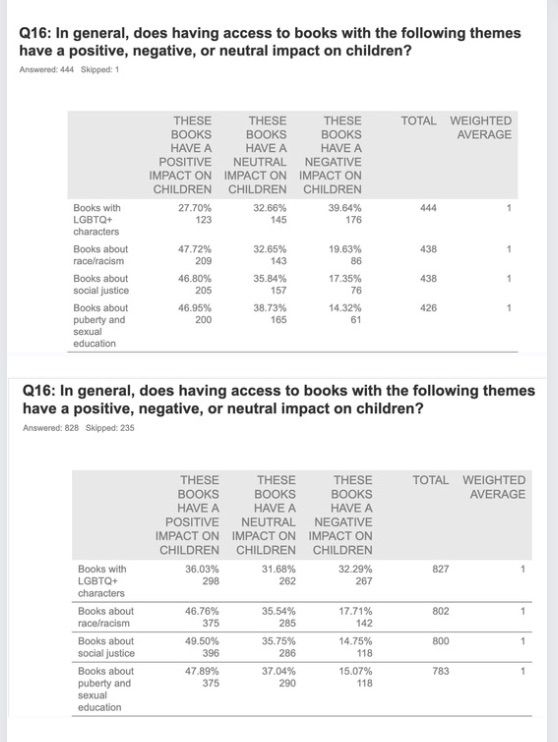

The subset was also more likely to say LGBTQ+ books have a negative impact on young people than the overall survey.

Pause with this for a moment. Of those who do not know how librarians select books, 40% think that books with LGBT+ characters have a negative impact on children. If the full survey’s 32% with this opinion were chilling, this is even more so. Indeed, in every category except for books about puberty and sexual education, this subset was more likely to judge the books are having a negative impact on children.

And yet, the subset is not only not thinking about book banning as an issue at the voting booth, they’re also unaware of the issue at all: 40% were “somewhat aware,” compared to the overall survey’s 31% response for this question; 22% were “not so aware,” compared to 15%; and 11% were “not at all aware,” compared to 7%. Despite being less aware than the overall panel, this subset was much more likely to believe in the very talking points pushed by the far-right when it comes to the impact of exposure to various topics on children. It makes sense, in some ways, that because these people do not know how books get onto shelves in the library, they are less aware of book banning, period.

The results become more confusing when asked for opinions on access to materials and, specifically, whether or not there are some materials in the children’s section that are inappropriate for all children and whether or not it is appropriate for teenagers to have broad access to materials. The subset was less likely to agree with the first and more likely to agree with the second. They are also unsure in their opinion more often than the full panel, which tracks, given prior responses.

And when it comes to whether or not librarians should be prosecuted for the materials in their collection, it should be a relief that the group who does not know how materials are acquired is significantly less likely to agree with that statement than the overall panel. Only 12% agreed, with 16% somewhat agreeing, compared to 25% and 23% respectively. That said, they were less likely to agree with libraries carrying books on complex topics for youth and more likely to disagree with the idea libraries should have books for youth that have LGBTQ+ characters. This group’s responses mirrored that of the overall when it comes to who should decide what books belong in the library — yes, despite not knowing how librarians make those choices, librarians topped the list of whose job that is (followed by parent groups, library boards, then local elected officials, which is the same ranking as the rest of the panel).

What does this all mean?

It appears that knowledge of how librarians select material plays some kind of role in how parents perceive the content of books. Specifically, more knowledge of library acquisitions appears correlated to more acceptance of books with LGBTQ+ characters and the belief that books about queer people have a positive effect on children. It is not a lack of access to knowledge of how librarians do their job, though — this information is widely available. It appears instead to be a lack of interest or engagement with this information or the perception that this information is highly politicized (it should be noted that the two options beyond republican and democrat are where those in other parties, such as constitutionalists, libertarians, greens, and so forth would “fit” — so for the sake of discussion they’ve all been flattened into either the “none” or “independent” category). The majority of this group does not see book bans as an important issue at the polls, and this group leans slightly more independent or altogether apolitical. The question becomes this: how do we get these people interested in knowing how their tax money is used to curate their local library and why it is crucial to offer a broad range of children’s materials across a myriad of topics?

We will need to come up with some creative solutions and fast — the impact of the talking points perpetrated by the far-right has made a mark here, especially when it comes to queer people.

Book Censorship News: November 3, 2023

Please take note: if your state has elections next week, you need to go vote. Learn who is running for school board in your district, and make sure you elect non-book banning candidates. Moms For Liberty has a whole page of endorsements — that’s who you want to avoid. This week’s book censorship news roundup is shorter than normal because so much energy right now has been spent in getting these book banners into offices of local power.

- Launching with good news, since the rest of the news isn’t so much: “A hundred and fifty challenged books will soon return to shelves after St. Tammany Parish library officials voted unanimously this week to rescind a new policy.” Note that this story is paywalled.

- A West Des Moines, Iowa, school board candidate (and Moms for Liberty “education chair” for Polk County) sought to sue the school district for “child pornography” over a pair of YA books in the school libraries. This series by the Des Moines Register is really good. I only wish they’d begun it sooner.

- Escondido Union School District (CA) just banned This Book Is Gay and Looking For Alaska. Check for the “goes against my religion” complaint from a parent.

- A Court of Frost and Starlight was just removed from Charlotte Mecklenburg (NC) schools.

- The public library in Graham, Texas, met this week to decide whether to ban the book We Need to Talk About Vaginas: An IMPORTANT Book About Vulvas, Periods, Puberty and Sex or to remove it. None of the options are good, and the opinions of the board are what you’d expect. The book is written by a reproductive endocrinologist FOR tweens, but that doesn’t mean anything. It’s been temporarily moved, but it might get banned anyway.

- Look what happens when a whole community — not just invested parties — gets a say in student education (aka: “parental rights”). The students in Garfield County, Colorado, will NOT be getting a conservatively-produced American history textbook for their curriculum. Everything you need to know about the textbook is in its title.

- Horry County Schools (SC) are very into banning LGBTQ+ books from their shelves. Among them is the just-banned — book number 13 — Gay and Lesbian History for Kids.

- “During the Oct. 17 meeting of the Hendry County School Board (FL), LaBelle City Commissioner Hugo Vargas brought up the issue of banned books, referencing a Banned Books Week display at Barron Library.” Oh, interesting, a city commissioner didn’t like that the public library put up a banned books display and decided to cry about it. What you need to pay most attention to here is that Vargas makes it clear this is not “just” about books at schools. It’s about access to books in the public library, too. Funny, that is exactly the opposite of what those who don’t want to be labeled book banners do. He didn’t get the memo.

- Campbell County Public Library (WY) hired its new director after the board fired the previous one because she wouldn’t ban books. We’ll see how quickly this guy begins to pull things…it’s an odd choice by the board since he’s been a non-book banner in his previously besieged Alabama library. Does he not know? He has to know!

- Hernando County School Board (FL) banned two more books: It’s So Amazing and The Perks of Being a Wallflower.

- Here’s a lady calling for Alpena Public Library (MI) to ban All Boys Aren’t Blue in the local paper. If you thought that someone like RFK performing the book in front of a federal legislative committee would be nothing but meme-worthy, then you’ve been asleep for a while. It’s impetus for the book banners to demand change. It’s wild that the letter writer gets her First Amendment Rights protected by the paper but demands they be revoked from an entire community.

- Elk Grove Unified School District (CA) continues its battle with the book ban happy board member and his public contingent.

- Same story, but this time in Kenosha, Wisconsin, schools where Moms For Liberty has sunk their claws into things.

- “Moving pornographic books from the teen section to the adult section is not ‘banning’ books. It is moving books. Read for yourself some of the books in the 14-year-old section at the Tyler Public Library here: https://substack.com/@dirtythirtycampaign. If moving a book is the same as banning a book, then the city manager is guilty of book banning. You know who actually does ban books? Communist countries like China. America does not ban books. This parent can obtain whatever book she wants from multiple sources.” Hmm, okay. Sounds reasonable since you use the same “reasoning” as every other right-wing book banning bigot. How do you explain the city commissioner in Florida, then, or the folks in Virginia who tried to get books pulled from Barnes & Noble? You don’t because you know that’s your target, too.

- Book banners are trying to get folks to defund the Ashland Public Library (OH).

- In Virginia, “A Hanover County student is pushing back against a school board decision to remove books from libraries. Her solution is to make the removed books accessible to students in alternate locations around the county. She’s created ‘Banned Book Nooks‘ at two county locations and is starting a program using tote bags to bring the periodicals directly to Hanover students.” A bandaid, but a student-initiated one.

- The Alabama Public Library Service will be leaving the American Library Association because of bigoted rhetoric about it. Again. They do not even do their own work.

- Athens-Limestone County Public Library Board (AL) got a surprise last week when the book banners showed up! Or, well, they don’t want books banned, but they want the library’s policies updated to make banning easier. They got this idea from the governor, who has been busily defaming libraries across the state.

- Rutherford County Public Libraries (TN) is creating new age-restricted library cards. Good luck to kids without parents to give them permission to access research or recreational reading that the library is now restricting from them. The free porn on the internet is worse than the anatomy textbooks in the stacks, just FYI.

- Boy Toy by Barry Lyga — a book published in 2007, just to contextualize — is under fire at Dover High School (NH).

- The Pennsylvania Senate passed a book ban bill (as in, to ban books easily, not to ban book bans). The thing is, the House wants to focus on real work, so it might not go anywhere. But given this is a state with some highly contentious school board elections, don’t let it go unnoticed.

- This story is paywalled, but it’s an update on Catawba County Schools (NC) now to offer alternates for parents when it comes to what books their kids have access to. Given how infested this district is with Moms For Liberty and how long this battle has raged, I suspect none of these are pro-intellectual freedom.

- Moore County Board of Education (NC) made some decisions over 9 contested books in the district — including removal from some schools — but the final decisions are tabled, and a verdict will be rendered in December. Come here for the people who don’t bother to understand the Miller Test.

- Students in Mat-Su Schools (AK) walked out in protest of the school board and its slate of regressive decisions, including book bans.

- “Wyoming State Superintendent of Public Instruction Megan Degenfelder unveiled a statewide policy recommendation from the state Department of Education concerning library book access at a press conference Wednesday. The policy is intended to advise school districts on the subject of sexually explicit library materials, while still leaving ultimate control of policy decisions to individual districts.” Degenfelder is the woman who was upset her child had a book about a puppy and who performed it for one of the federal subcommittee hearings to get attention for her queer panic. That…will impact the entire state of Wyoming.

- A member of the Bartholomew Consolidated School Corp. school board (IN) wants to label “controversial” books. Do explain whose idea of controversial gets the label or if the entire library gets labeled because everything is controversial to someone.

- A Moms For Liberty school board candidate in Downingtown (PA) made up a college and used that made-up college to draw attention to “damaging” books in the schools. These. People. Want. To. Govern. Schools.

Also In This Story Stream

- How to Fight Book Bans in 2024: Book Censorship News, April 26, 2024

- Google Is Destroying Your Access to News: Book Censorship News, April 19, 2024

- What Young People Can Do About Book Bans: Book Censorship News, April 12, 2024

- Sexual Assault Awareness Month & Book Banning: Book Censorship News, April 5, 2024

- How Public Libraries Are Targeted Right Now—It’s Not “Just” Books: Book Censorship News, March 29, 2024

- The 2024 Lambda Literary Awards Shortlists Are Here

- You’re Wrong About These Common Myths About Book Ban: Book Censorship News, March 22, 2024

- State Anti-Book Ban Legislation Updates: Book Censorship News, March 15, 2024

- They’re Dismantling Higher Education, Too: Book Censorship News, March 8, 2024

- The Landmine of Common Sense Media: Book Censorship News, March 1, 2024