Always Gold, Never Silver: Wealth, Art, and Vampires

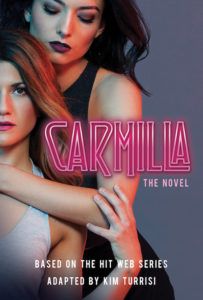

Sponsored by Carmilla by Kim Turrisi from KCP Loft.

An adaptation of Shaftesbury’s award-winning, groundbreaking queer vampire web series of the same name, Carmilla mixes the camp of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, the snark of Veronica Mars, and the mysterious atmosphere of Welcome to Nightvale.

An adaptation of Shaftesbury’s award-winning, groundbreaking queer vampire web series of the same name, Carmilla mixes the camp of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, the snark of Veronica Mars, and the mysterious atmosphere of Welcome to Nightvale.

There is a scene in Interview with the Vampire where Claudia (played by Kirsten Dunst) is receiving piano lessons. She is disciplined by her tutor and, ultimately, eats him (as I am sure many a child in piano lessons would like to do). There’s a lot of subtext in that scene, built into the rest of the film with costume, set design, and camera work. We see Claudia, done up like a doll in luxurious clothing (and even acquiring a doll doppelgänger), a contrast to her origins, learning to play an instrument by a paid tutor. We have dressed up a monster in the hallmarks of civility—in pretty clothing, in a lovely setting, making music. It leads me to wonder, is the vampire an art consumer?

Lace Sleeves and Culottes

Foppish vampires are a trope all their own. We can look at Jemaine Clement and Taika Waititi’s What We Do In The Shadows as the culmination and evisceration of this trope. In many ways, this an aspect of queer-coding characters, establishing these male (often foreign) monsters with what would now be considered effeminate tendencies. Fanciful clothing, riches, luxuries, paintings, antiques, even if decrepit, are tied to vampires and vampirism. These Rococo-esque trappings are also now queer coded because of the inversion of what Western society deems masculine or feminine.

Back in the 18th century, when France was the center of art, culture, and fashion for a Eurocentric history, for a brief few decades a Rococo style was the height of masculinity. Pinks, powdered wigs, and heels were seen as signs of culture, or wealth, or masculinity. As politics change, so do gendered concepts, NS what were once signs of hyper-masculinity become consigned to the opposite and often the lesser status. Hence a sort of comedic or unsettling foppishness that becomes an othering technique.

What is Art? (Baby Don’t Bite Me / No More)

More than that, though, vampires, when either comedic or sinister villains, seem to desire a life filled with pretty things and associated with the consumption of art.

Before we can even talk about vampire art collecting (1), we kind of have to talk about what art is. Because what is and isn’t art is derived directly from people who have Power with a capital “P.” Whether that power is institutional, monetary, or cultural, people in power tend to have the ability to define what is and is not art or what counts as artistry or who practices it. They also get to define who gets to consume art.

In the spirit of ignoring that caution and caveat, we’re going to talk about art in the most general of terms. In general, when we think of art, we tend to think of things like classical paintings, sculpture, music, performance, literature. We also, often think of art as “pretty” or “aesthetically pleasing.”

Bloody Conspicuous Consumption

Vampires, mythologized as the perpetual other, can often be portrayed as the wrong type of consumers. Not only do they consume an odd food choice (human blood), they are out of fashion. As creatures out of time, their tastes in art or decor are seen as out of step with whatever society they reside in. Or their extravagances are odd and out of place in comparison with the rest of society.

Vampires, mythologized as the perpetual other, can often be portrayed as the wrong type of consumers. Not only do they consume an odd food choice (human blood), they are out of fashion. As creatures out of time, their tastes in art or decor are seen as out of step with whatever society they reside in. Or their extravagances are odd and out of place in comparison with the rest of society.

For instance, when Jonathan Harker is staying with Count Dracula, he remarks on the housewares: “There are certainly odd deficiencies in the house, considering the extraordinary evidences of wealth which are round me. The table service is gold, and so beautifully wrought that it must be of immense value. The curtains and upholstery of the chairs and sofas and the hangings of my bed are of the costliest and most beautiful fabrics, and must have been of fabulous value when they were made, for they are centuries old though in excellent order. I saw something like them in Hampton Court, but there they were worn and frayed and moth-eaten.” (Dracula, Bram Stoker).

Dracula’s ostentatious presentation is at odds with the lack of visible servants, and with missing mirrors in Harker’s estimation. This show of wealth, wealth that is out of date. It should be noted that Hampton Court, which was famously attached to Henry VIII and built in the 1500s, was a public museum by Stoker’s time.

A Vampire Like Me

Note that this consumption is something that becomes more prevalent when vampires are the aggressors, villains, or characters in transition. It seems this wealth or obsession with art objects gets removed (somewhat entirely) when the vampire is the protagonist.

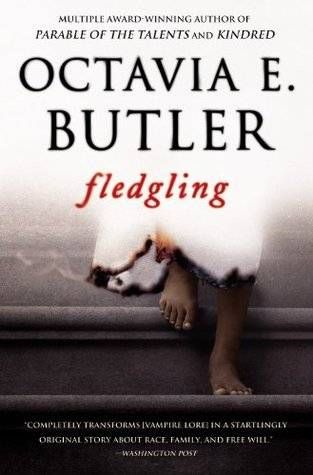

We can look to characters like Shori in Octavia Butler’s Fledgling as someone who is largely sympathetic and not particularly obsessed with luxury objects, at least in the beginning. Shori’s main goals at the beginning of the book are self-discovery and survival, and as she learns about the Ina, we discover a society also intrigued with niceties. This contrasts with Shori’s first appearances, wearing oversized clothing, to that of her Ina family, living in a large set of estates.

We can look to characters like Shori in Octavia Butler’s Fledgling as someone who is largely sympathetic and not particularly obsessed with luxury objects, at least in the beginning. Shori’s main goals at the beginning of the book are self-discovery and survival, and as she learns about the Ina, we discover a society also intrigued with niceties. This contrasts with Shori’s first appearances, wearing oversized clothing, to that of her Ina family, living in a large set of estates.

The more “traditional” vampires of her Ina family, able to acquire wealth through long lives and generations, surround themselves with the trappings of wealth, with fine furniture and artistic objects.

Of course some of this could also have to do with the relative ages of the vampire, younger contemporary vampires being less inclined to partake in artistic collection. Then again, these vampires tend to be more sympathetic if there is any longer-standing development. Or if those vampires are non-white, as is the case of Atl in Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s Certain Dark Things. In these cases, there isn’t a vast history of wealth acquisition.

Oh You Pretty Thing

There is something oddly endearing about how vampires are portrayed to interact with the aesthetics of the world around them. In particular when those vampires are portrayed less like animalistic feeders and more like the bourgeoisie. It’s altogether intriguing how much we can tell about a vampire by the way they furnish and decorate their surroundings or the music they listen to or the art making they want to partake in.

While the consumption of wealth objects can be seen as something othering (3) when not done with societal norms, it’s altogether a little sympathetic to want to surround oneself with pretty objects. It’s a humanizing thing to want to collect lovely objects, and it gives us a little bit of a sense of the humanity in the monster.

(1) I’m sure someone has done the provenance research on this. (2)

(2) That was an art history joke, and yes, it was lame.

(3) Special credit to Elisa Hanson’s Vampire Reviews and multiple videos discussing vampires as the classic “other”.

- 9 Vampire Novels With a Unique Twist

- The Evolution of Vampires

- 7 Wonderfully Diverse Vampire Novels

- 4 Takes on Non-Western Vampires

- Lesbian Representation in the Vampire Classic CARMILLA

- Fangs for Nothing: 12 Underappreciated Vampire Novels

- How Teaching 6th Grade Made Me Unconditionally and Irrevocably Love TWILIGHT

- The Best Vampire Adaptations

- The Vampire as Sexual Predator in LOOK FOR ME BY MOONLIGHT