How To Fight Book Bans and Challenges: An Anti-Censorship Tool Kit

Find an updated guide for fighting book bans in 2024 here.

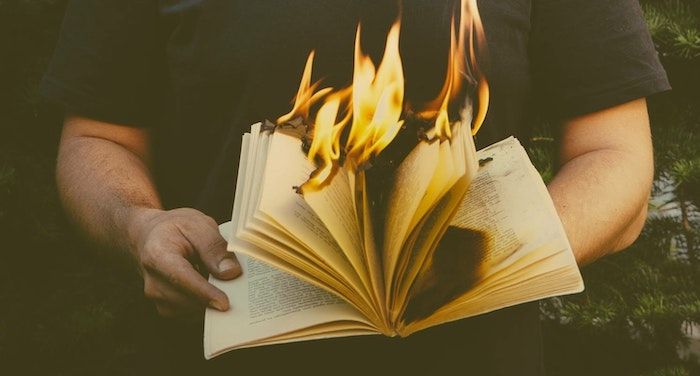

Book challenges aren’t new, and neither is the “celebration” of banned books which occurs for a week at the end of September each year. The annual event began in 1982 as a response to a “sudden surge” of book challenges in schools and libraries, and one of the most well-known outcomes of Banned Books Week is the release of the prior year’s “most challenged” books. These titles emerge from the American Library Association’s Office of Intellectual Freedom, who compile the media reports and librarian/teacher submissions of challenged books. The list makes a splash, most notably in recent years for how clear it is that queer books and books by authors of color, as well as books about sexual health, are under fire.

But when Banned Books Week ends, so often, too, does the energy of highlighting book challenges and censorship. In too many cases, the “celebration” leans heavily into talking about the books in specifics — a particular title was challenged or removed from a classroom because of a specific reason, which is then repackaged in media stories to make it sound as though the people behind these challenges are a minority, oddballs, conspiracy theorists, or simply the kind of people who are afraid their children might be exposed to queer or Black characters.

This is an oversimplification. The lack of nuance only furthers the real threats to intellectual freedom.

Censorship happens when a group or organization works to suppress speech, books, movies, and other materials. This is too often the sole focus on events like Banned Books Week, and the attention gets turned onto the censors and their agenda, as opposed to the real freedom under attack. That attention then further fuels their fire and provides the spark for more fires to ignite, as that attention is a commodity these groups crave. It is in no way about fear of their children learning about groups different than them. It’s about white supremacy. It’s about power. Calling it anything less than that diminishes the responsibility there is on gatekeepers to uphold intellectual freedom and the First Amendment.

Censorship also happens, though, when materials never get the opportunity to be included in a collection. This quiet or silent censorship is insidious and dangerous, and it emerges in two distinct ways. The first is when a librarian or educator purposefully doesn’t include material in their collections because it counters their own beliefs. The second is when those gatekeepers elect not to purchase or promote materials because of the fear they may be challenged. A book that may be an essential addition to shelves never gets purchased because the person in charge of making said purchase bows to fear or intimidation or the possibility of either.

This censorship is not recorded.

Since 2004, over one quarter of U.S. newspapers have disappeared. Many citizens may not see the problem with this as digital media has filled in many of the gaps. But digital media is not the same as local media, and for communities without local newspapers, this means communities are also left without an unbiased resource for understanding what’s going on in their backyard.

Newspapers are watchdogs, historically serving as a check-and-balance to civil organizations. Reporters showed up to board meetings across their communities and reported on the happenings. In most cases, this isn’t especially noteworthy work; it’s a beat. But those beat reporters give community members all of the information they may need before casting a ballot, before showing up to speak out against new town proposals, before showing up to a school board meeting, and so forth. Local journalists know the town they’re covering, usually because they live there or are deeply embedded within the community.

With diminishing local news outlets comes the disappearance of local reporting. No longer is someone sitting at every board meeting to report on what’s happening; no longer is there that check-and-balance system to report the conversations happening both by elected and appointed officials and those within the community who show up.

It isn’t until there’s a particularly salacious local story — think pink dildos or an unhinged rant about anal sex — or until a group shouts loud enough — think high school students protesting — that it makes any sort of news. Then, it might hit local news. In the linked pieces, the stories were juicy enough to make major outlets, seeing the opportunity for the click-outrage-share cycle. It is not that the writers don’t care about these issues. Most of them are deeply disturbed. But, until the story can pay for its space by means of clicks, it isn’t worthy.

It’s white supremacy and power which drive those click-y stories. Those stories then repeat themselves in other communities.

The click economy is a major factor in the decline of local journalism, and it’s also why you don’t hear about the tremendous number of censorship stories happening on the local level every single day across America. Where there were once reporters or citizens sitting at civic meetings to see and share what’s happening, now those seats are empty and the stories go unheard.

That doesn’t mean those in the community don’t know what’s going on. Indeed, when it comes to librarians and teachers, it’s likely they know not only what’s going on, but also the rumors about what’s happening. They’re aware of groups showing up to school or library board meetings to challenge policies or curriculum or collections. They’re hearing about what those groups plan to continue to do to pursue their agenda. They may be hearing from individuals dogging board members to bow to pressure to remove a title from a library shelf.

Without support — and indeed, the local media is a tool of support in communities, particularly in their roles as watchdogs — it’s impossible to overstate how easy gatekeepers can fold to that pressure. They may or may not have supportive administration, but in either case, knowing a choice you make for your community may put your job in jeopardy can and does too easily mean that choice simply isn’t made.

Celebrating banned books ignores the vital need to protect intellectual freedom. It fails to account for the very real humans whose livelihoods are at stake for doing what’s right. Instead, it further serves white supremacy and power, centering the voices of outrage, rather than those whose voices have been forgotten, ignored, or suppressed completely.

Take, for example, what’s happened and continues to be happening in Irving, Texas. A far-right Christian group formally challenged the book Jack of Hearts (and Other Parts) by Lev Rosen this summer. Formally is important here. Norman and her compatriots have been showing up to school and city board meetings for nearly two years to challenge queer materials in Irving Public Library.

No local media covered the summer formal challenge, despite the fact that Irving is a large suburb in the Dallas metroplex.

Jack of Hearts went through the library’s challenge process and remains on shelves in the public library. This is thanks to a supportive city council, as well as a strong leadership team at the library who not only believe in the power of queer books like this, but who fiercely defend the right for all of their citizens to have access to as wide a range of materials as possible.

What hasn’t been reported, though, is that Norman and her group continue to show up to city council meetings. Each of the meetings where they come is a parade of more and more unhinged comments from “concerned citizens,” demanding the council do something about the books in the library.

It also hasn’t been reported that Jack of Hearts is not available in the Irving Independent School District.

Norman is an employee in the district.

It’s unknown whether the book was available in the school libraries prior to the litany of complaints. But certainly, school libraries operate differently than public libraries in so much that they do serve in loco parentis. Where public libraries put the onus on parents to monitor what their children consume — as they should — school libraries have more responsibility for maintaining appropriate collections for the students they serve.

Jack of Hearts is for readers 14 and up, with a range of positive book reviews from trusted sources. The book is appropriate for the school library, with supporting evidence, but it was either pulled or never given the chance to be on shelves at all. With groups like the one pressuring the public library, it’s hard to blame a school library for not wanting to fight that battle, despite the fact that is the job.

Without local media on this beat, the story disappears from public view. Out of sight, out of mind.

But the challengers remain.

It’s a privilege to consider book bans a thing of the past or a thing that doesn’t impact readers. It is easy to believe getting a book is as simple as a one-click at an online retailer. But it’s not — and that mentality in and of itself is a product of white supremacist thinking. Book challenges and bans harm the most vulnerable in communities who don’t have access to finances, time, or transportation to acquire a book no longer available to them in the places where they are: classrooms or libraries.

It’s also a privilege to suggest book bans are great for authors and book sales. Sales increase for some authors, sure. But for the bulk of authors who experience book bans, there’s no noticeable difference in sales because often, they don’t even know a book has been challenged or pulled from shelves. No author writes with the hopes of gaining notoriety or sales by a book being inaccessible to its intended readership. They write to reach those readers.

What gets forgotten in discussions of censorship, too, is the incredible power of the public library. No other American institution is tasked with unequivocally protecting the First Amendment and intellectual freedom specifically. This isn’t a politically negotiable assertion. Libraries are founded on and protect these liberties and need to continue to do so. It’s not about banned books. It’s about the rights imparted to American citizens as outlined in the Constitution and Bill of Rights.

So what can be done to push back against book challenges and bans? Without structures like local journalism to stay on the beat, how does the average citizen or average librarian, school librarian, or administrator stay abreast and work to ensure intellectual freedom remains a fundamental right? There are several potent tools and methods to engage with, whether you’re able to dedicate a few minutes to the cause or lend hours of time to do the work. These lists are split up for citizens and for those inside libraries, but know that these are not mutually exclusive lists.

Methods and Tools for Combatting Censorship in Your Community

For Citizens

Begin first by keeping your local school board, library board, and city council’s information handy. Where and when do they regularly meet? Where can you find the minutes from previous meetings? Know where to find agendas, as well as board packets — those packets may be made freely on the appropriate government website or you may need to put in a Freedom of Information Request for them (this is your right). Keep the phone numbers and email addresses of each member of the representing boards accessible and updated. Many of these boards record their meetings, so bookmark those livestreams or archives.

All of these paper trails are resources granted to you by federal and local laws. Utilize them to know what’s going on where you live.

Keep up with your local newspaper if you have one. If you don’t have one, learn who covers your community for regional papers or national bureaus. Even mainstream, major outlets like Business Insider or Propublica have reporters assigned to different regions of the country. The problem is, of course, they’re covering a large region, rather than a single community or county. These reporters are, however, always seeking the stories that matter, so utilize them as resources.

- Vote. Yes, it’s as simple and straightforward as this to get started. Local elections matter, and in many places, library boards and school boards are elected positions. Know who is on the ballot and ask them questions at open forums or via their social media and websites. Ask them where they stand on censorship and the rights of a community to access the information they desire. The Niles Public Library serves as a stark reminder of what happens when turnout for local elections is minimal — the minority’s voice is heard loudest.

- Serve on a Board. If you have the time, serve on your local school, library, or city council/board. For appointed positions, apply; for elected positions, run. Every civil body operates differently, so get to know how these positions work, how often you’re expected to attend meetings, and what your role may be in the broader community.

- Show Up to Meetings. Open comments from the public are given space at civic meetings. Typically, this is time at the start of a meeting, and often, there’s a time limit on open comment. It varies community to community and board to board. This is crucial because people who have a problem are the ones who always show up. People who are happy or unaware of how things are going do not show up. Your comments do not need to be scripted or deep. Simply taking ten minutes of your evening to show up and tell the council you’re happy with how the library has such a great collection or that the children’s programming in the school library has been appreciated is doing the work. Those comments not only remind gatekeepers of the power of their job, but those boards hear and see that, too.

- Write Letters. Can’t show up to meetings? That’s fine — email your city council, email your library’s administration, and email the school librarian. Tell them you love what they’re doing and why. These letters matter, and even if your letter is handed to the library worker shelving books because you don’t know who best to direct it to, the letter will show up in board packets and reports, as proof of the vitality of the organization and how it serves its community.

- Talk to the Newspaper. Maybe, if you’re lucky, you have local newspapers. Utilize them. Write letters to the editor — which are often capped at 300 or so words — extolling the virtues of the library. Name names, name book titles, name programs. Again: the majority of voices on those letters to the editor page are unhappy people. They rarely are people who are happy. Add a voice of praise and do it often. It’s a simple as setting a quarterly or monthly alert to spend five minutes brainstorming praise, writing it, and sending it through the paper’s submissions, often right on their digital editions.

- Correct Misinformation. Taking into account the above, speak out and write in when misinformation about your library, its materials, or its actions are shared. In Irving, one of the angles of challenge for queer books was that the YA section was nothing but LGBTQ+ sex books and there were no books about other topics in the library. This was patently untrue: the library had books on every topic claimed to be lacking and the YA section is packed with books on every topic imaginable, for readers of all age levels and tastes. This misinformation is what many will latch on to and use as a means of denigrating the library and its work, then it is wielded to fit the white supremacist agenda.

- Familiarize Yourself With a Library’s Collection Development Policy. All public libraries and most, if not all, school libraries have collection development policies. Often, they’re available on their websites. These policies govern how and why materials are acquired for a collection. Keep these handy and be familiar with them, as these are tools helpful for combatting censorship — and encourage your libraries to make these policies accessible online, as well as regularly updated. If there’s something amiss in the policy, ask questions.

- Submit Materials Requests. Most public libraries allow users to submit titles for the collection. Let your library know you want books by authors of color and queer authors. Your request can be as simple as the name and title or as in-depth as name and title, as well as why the book should be in the collection (and you can absolutely include reviews, if you want). Submitting requests makes it clear to purchasers these materials are desired and allows a paper trail to exist as evidence of this community need.

- Ask Why Items Are Not Purchased. Is there a book you’ve requested or have seen in other libraries that is absent in yours? Ask why. There might be a legitimate reason for this — budget constraints, for example, limit how many books can be purchased in a fiscal year — but the act of questioning may be the wakeup call a staff member needs to pause and reflect on their own biases and fears. Again: public libraries are tasked with protecting intellectual freedom. You’ve got a right to ask why those freedoms aren’t always exercised within the institution.

- Report Hate Groups. Contact local media and local authorities about hate groups when they emerge. These groups work to target policies they don’t like with the goal of maintaining white supremacy. Call them out on social media, then follow it up with evidence of hateful actions where you can. This is standing up in support of libraries, of intellectual freedom, and of the First Amendment.

- Stay Alert. Distraction is harmful. Too often, we forget about a problem or an issue when it feels like it’s been resolved. The fact is, protecting Intellectual Freedom is every day work. It doesn’t end, and it doesn’t magically resolve itself. Keep alert, keep fighting, and keep finding more allies for the cause in your community. Show up together.

- Donate Money. Have some money you can donate to the library? Do it. Go through their Friends group or Foundation, if they have one, or simply ask if they have a donation spot on their website where you can leave some money. Even a few dollars will be stretched and put to tremendous use.

Do not take for granted the freedoms given to you. The fact is, those working to actively censor material are working to take them away. We’re living through historical times and they mirror previous generations of “historical times”: white supremacists are working to limit access and control the information made available to citizens. They’re denying the existence of people of color and queer people by working to remove these materials. Public libraries have and will continue to do great work with building necessary collections representing a diversity of viewpoints, upholding their roles in the country. But those who seek power and control don’t want that to be the case, and in too many cases, libraries back down in order to not cause a stir (in and of itself an issue with the stereotypes and impressions of who works in a library made more damaging with the loss of local media to prove otherwise).

For Gatekeepers (Educators, Librarians, Administrators)

Libraries have incredible responsibility, as do teachers, though the regulations within the classroom are far more politically limiting than in public libraries. The bulk of people working in these institutions are doing their best, and they’re doing so with little support vocalized from the community, compared to the criticism.

Remember your purpose as a radical institution devoted to upholding the fundamental rights of citizens. You are the bastion of intellectual freedom. It doesn’t matter what that looks like — children’s puppet story times, crime lover book clubs, ditching late fees, whatever — these are all part and parcel of what makes the library the institution that it is. It is a third space where anyone can exist without any purpose. The library is the purpose.

In addition to all of the above items, some specific tools for gatekeepers to combat censorship include:

- Have a Formal Review Process. Update or rework your current materials review process and align it with your purpose as an institution of intellectual freedom. Explain where and how items are added to the collection, as well as how items recommended by citizens are included. Put this on your website and make it readily accessible, right alongside your forms for formal material complaints and forms for suggesting materials.

- Market Those Materials. Put it on your front doors that the library is an institution of intellectual freedom. Promote that you have these policies. Book displays are part of the work of a library, as are reader’s advisory guides. So, too, should be your marketing of what it is you truly do in the library.

- Consider Ditching Celebrations of Banned Books Week. Rebrand the concept as Intellectual Freedom Week or a week dedicated to protecting the First Amendment. Get rid of the week-long festival all together and focus instead on working these issues into everyday discourse as Intellectual Freedom or, to put an even finer point on it, upholding the First Amendment rights guaranteed to all U.S. citizens. By highlighting banned or challenged books, you give more attention to those who want to uphold white supremacist ideals, even if the intention is to showcase the books. Just put the books on displays all year long. Make those displays when it’s unexpected and give it a non–Banned Books theme. Get all of this in front of your citizens all the time, rather than the one time it’s seen as the “right” time.

- Befriend the Media. Talk to your local news. Talk to regional news. Talk to national news. Get beyond talking with library-specific organizations — they don’t need to be convinced about libraries or intellectual freedom (even if they do need to be convinced to change the language they’re using). These outlets are your supporters and your allies in defending the First Amendment.

- Recognize Your Staff in Meaningful Ways. Remind them you’re supportive of them because they’re professionals hired for their skills, talent, and intellect to do their jobs. Kudos do good, but raise those kudos to the level of your library board, as well as city council. Then make spaces where staff feel they can go when necessary. Do they need a few therapy sessions when dealing with a community book challenge? Do what you can to provide that. Do they need flex time or the ability to do some of their work from a non-library space? Make it happen. And don’t just make these things happen. Talk about why these decisions are made so that everyone understands that these accommodations are necessary to do the tremendous job of upholding intellectual freedom.

- Ask Questions and Be Open to Questions. Know why books aren’t being purchased. Be prepared to be asked about the books which are purchased. It should be an expectation of those in charge of working in places of intellectual pursuit to expect engagement on their choices and likewise, feel supported — or challenged! — on them.

Don’t fall asleep. It’s easy to become complicit, especially during busy seasons. But it’s during these times those who wish to dismantle public institutions gain ground, recruit members with their ideologies and propaganda, and act as a group or individuals to tear things apart.

Constant vigilance is exhausting, but if freedom of information and access to ideas is foundational to you, the work is essential.

- It’s Still Censorship, Even If It’s Not a Book Ban: Book Censorship News, August 30, 2024

- Are You Registered to Vote?: Book Censorship News, August 23, 2024

- What Is Weeding and When Is It Not Actually Weeding?: Book Censorship News, August 16, 2024

- How To Explain Book Bans to Those Who Want To Understand: Book Censorship News, August

- A New Era for Banned Books Week: Book Censorship News, August 2, 2024

- The Ongoing Censorship of High School Advanced Placement Courses: Book Censorship News, July 26, 2024

- The Quiet Censorship of Pride 2024: Book Censorship News, July 19, 2024

- Survey: What Happened During Pride Month? Book Censorship News for July 5, 2024

- The First American Union Understood The Necessity of Public Libraries and Education: Book Censorship News for June 28, 2024

- Here Come The Public School Closures: Book Censorship News, June 21, 2024