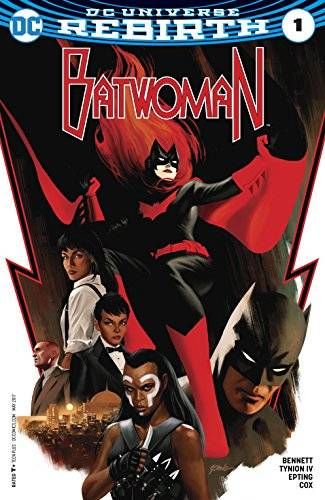

What Batwoman Can Do

This is a guest post from Asher Guthertz. Asher studies film at UC Santa Cruz, but mostly he reads comic books and wishes he was a superhero.

One of the central preoccupations of the story so far is the question Kane asks in her opening monologue: “What can Batwoman do that Batman can’t?” The series addresses the question by drawing on, but subverting, classic Batman conventions. Julia Pennyworth, for instance, is Alfred’s daughter, and occupies his role, to an extent. She talks in Kate’s ear, offering combat advice and tech support, and in a sweet moment at the end of the first issue, she makes Kate a cocktail. She makes one for herself too, though. While Julia could be the Alfred of Batwoman, she refuses to take on a role of subservience. Julia and Kate continually argue, for example, over who is going to do the dishes. In Julia’s insistence that she is not Kate’s butler, the book reimagines the role of colleague.

Coryana, the mysterious island at the center of Batwoman works as a reimagining of the foreign space in Batman comics. The Batman myth goes that a young Bruce Wayne disappears, often to a vaguely defined location in Asia (the Himalayas, in New 52 continuity) to learn how to be Batman. This origin story, not confined to Batman, is an orientalist myth that the East is filled with hidden knowledges ripe for the taking by white people. Coryana appears so far to be the land where Kate Kane became Batwoman, but there are nuances in Coryana’s representation that differentiate it from a Batman origin land. Bennett and Tynion tell us off the bat that Coryana is in Greece; in this small way they make clear that their mythical island won’t reiterate myths of Asia. Coryana is also filled with a diverse menagerie of criminals, expatriates from different ethnic backgrounds and with different moral codes. Instead of Kate being taught by an ethnic group, she is taught by an occupational one: criminals.

In the Batman myth, the land comes back for revenge. Rhas-Al-Ghul decides to kill Batman; the very people who taught Bruce Wayne are transformed into the villains of the story. In Batwoman though, she is pulled back to the land not at the behest of the people of the island (in fact, no one wants her there) but because of the threat of industrialisation. The Many Arms of Death, the evil company with the bad-ass name that Kate Kane has been on the hunt for, has bought the entire island, and wants to blow it up. The kicker is that from the beginning of the story, the Many Arms of Death have said they want to kill “the most people from the most nations.” Ie., they want to blow up Coryana exactly because of its multi-ethnic population. The villain of Batwoman is landowning white people who want to destroy a racially diverse space. Batwoman has only been around for three issues, and already it has become an interesting reworking of the Batman origin story. I hope that Bennett and Tynion IV are allowed to stay on the book and continue to answer the question: What can Batwoman do that Batman can’t?