When Your Child Reads NEW KID Over Your Shoulder

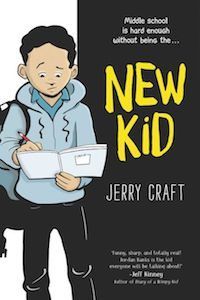

Last year, I picked up Jerry Craft’s New Kid from the library. I had heard on a podcast that Craft uses inventive graphic novel devices to tell a story about middle schooler Jordan Banks transferring to a prestigious private school where he is one of the few students of color. Craft mentions that the story was influenced by his own experiences growing up.

What I didn’t anticipate, however, was how reading this graphic novel to myself, on the couch next to my 2nd grade child, would spontaneously spark conversations about racial bias, stereotyping, and microaggressions.

Jordan, the narrator of New Kid, bonds with Drew, a fellow student of color at his new and mostly white private school. They commiserate about the assumptions that teachers and librarians have made about books they would connect with—books about slavery, struggle, and street life. I was so engrossed in the images of several book covers with increasingly dire titles that I barely noticed my daughter hovering over my shoulder, equally captivated.

“That’s like how a lot of books with brown girls I see are about how hard it is to be brown.” Now, this is a conversation we’ve had before—I’m a brown educator raising a biracial reader—but this impromptu communal reading experience of New Kid stretched our conversation in new directions. “Why did the teachers give him those books?” she wondered aloud. We talked more about how Jordan and Drew might’ve felt when they were given those books and why. She had a lot to say about the limited range of topics covered in the books she’s read with main characters of color.

“Where are more books with a half-Indian, half-white girl talking about funny things from her everyday life?” And, she wondered, “Why aren’t there more books where a white kid moves to another country where he’s the one who looks different, where he’s the new kid and has to fit in?”

Jordan’s teachers repeatedly confuse the names of the few Black kids at the school. As readers, our frustration grows with theirs. Our jaws clench tighter and tighter as we hear the wrong names in the hallways, classrooms, and fields. When one teacher finds and reads Jordan’s private sketchbook, she discovers that he views her casual errors with his name as an indication that he is “insignificant.”

I predicted that this would be a turning point in the story—that the next page would finally reveal a remorseful and reflective teacher. She’s drawn with a downcast expression as she hunches over Jordan’s sketchbook, almost appearing to look inward. But she actually responds with disappointment in Jordan’s “anger.” She sees his voice and artwork as a threat against her and the school, despite the nuance embedded in his observation.

Still peeking over my shoulder, my 2nd grader stops me from turning the page. She needs to process this scene longer. So do I. This time I’m the one thinking aloud, “Why is she mad at him? Why can’t she admit that she’s been using the wrong name?” I expected a typical 8-year-old response like, “She’s mean!” But I was surprised to hear her recall a time at school when a peer did not appreciate her own critical feedback. “People don’t really hear you when they think they’re being attacked,” we concluded.

I also knew there was more to the teacher’s labeling Jordan as angry, so I pointed out the drawing of a version of Jordan that fits the “angry Black guy” stereotype—no shirt, tattoos all over his chest, dark shades. He’s drawn outside the panels and frames on that page, outside of what’s real, and my daughter immediately noticed that the picture was somehow “wrong.” When I asked what it could have to do with the teacher’s accusations of anger, we were able to dive deeper into the complex power dynamics at play in this scene.

But all characters in the story, and even us readers, are susceptible to using stereotypes to make assumptions about others. Craft’s clever use of emojis got us examining our own implicit biases as we turned the pages. When the librarian recommends books about the mean streets to Black students, she’s surrounded with bland smiley face emojis. She thinks she’s being kind, helpful even, taking the time to match kids with books. But the emojis highlight the tension between her self-perception and the icky feelings her actions invoke in Jordan, Drew, and Maury. From their perspective, the vacant emoji smiles make the faces look clueless. The librarian’s attempts at connection are perfunctory and superficial.

Just a few pages after the library scene, those same smiley emojis surround Ashley, who has just secretly gifted some questionable items to Drew: a Black Santa cookie, a gift card to KFC, and basketball shaped cookies. Drew suspects her gifts are another example of others only seeing him as a Black kid.

Like Drew and Jordan, my daughter and I had been conditioned at this point in the story to interpret those emoji faces as a signal that Ashley was making racist assumptions about what a Black student would want as a gift. But we turned the page to discover that, in this case, Ashley used what she had learned about Drew as an individual to decide on gifts she knew he’d like. “Why did we assume Ashley was being racist?” I asked out loud. Together we compared the librarian’s gesture to Ashley’s. “The difference is that Ashley wouldn’t give those gifts to just anyone who is Black.”

Just as Drew and Jordan are continuously attempting to figure out if others are seeing them as individuals or as stereotypes, as readers we are also closely examining the characters’ intentions, unsure if we’re encountering a microaggression or genuine connection, not unlike in our own lives.

Of course the benefits of reading aloud to children are well known. Sharing stories means we wonder together, ask questions, and form a common language that we can use to talk about life outside the story. But reading a graphic novel to yourself, near a younger reader, can invite those same (and new) conversations in a refreshingly spontaneous way. Graphic novels and comics allow for an impromptu communal reading experience that’s harder to create with a prose text. Not surprisingly, my 2nd grader isn’t as compelled to read over my shoulder when I’m holding a text dense with prose. She can’t glance at a page and immediately engage with the story the way she can when I’m reading a graphic novel.

And with a Newbery award winning graphic novel like New Kid, the clever arrangement of words and pictures, the contrast between what’s in a frame and what’s outside one, and the carefully chosen details in each panel’s drawings invite the kind of critical thinking and self-reflection that are part of any meaningful reading experience.

Have you ever read a graphic novel in the vicinity of a young reader? Do they not eventually peek at your page, hover, and pick up the book when you put it down? If you want opportunities to hear your child’s thoughts about an issue or experience, continue to read any books that engage with those topics to your child. But also consider picking up a graphic novel that addresses those ideas. Casually read it to yourself—near your child—not to them. The conversations that can happen might surprise you.