Facts in Fiction

This is a guest post from Trisha Brown. Trisha hails from one Washington (State) and now lives in another (DC). She spends her days working in social policy and her nights defying common sense notions of how many books a 500 sq. foot apartment can reasonably hold. Her romance novel review column, “Restricted Reading” runs at Brightest Young Things. Follow her on Twitter@Trisha_reads.

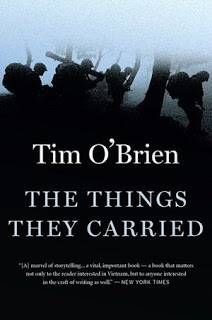

The Things They Carried is a fictional work that reads like a non-fiction one. So much so, in fact, that after about 100 pages, I did a quick internet search to verify that the stories in the book were fictional. What I learned from both a bit of background research and from the book itself is that the stories both are and aren’t true. The character of Tim O’Brien talks a few times in the text about how the stories are invented, but he also tells his readers “story-truth is truer sometimes than happening-truth.” The Things They Carried is almost as much about the art of storytelling as it is about the war, and O’Brien dedicates much of it to explaining and demonstrating that even if the stories are fictional, that doesn’t keep them from being real.

We think of fiction and non-fiction as two distinct entities, but they’re actually two ends of a spectrum. Most books exist somewhere in the middle, somewhere between Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and an algebra textbook. Authors of historical fiction research the times and phenomena that make up their settings so that their stories are realistic. Conversely, authors telling their own stories and giving us first person accounts aren’t always dealing entirely in facts. Shonda Rhimes, in the first chapter of her non-fiction book Year of Yes, goes so far as to acknowledge that although it is her intention to tell her stories as they truly happened, she’s a writer, and as such, her job is “making stuff up.” She warns that she may unconsciously revert to that habit.

Sometimes, the distinction between fiction and non-fiction is inconsequential. Fiction can be a better conduit for reality; straight non-fiction lays out the facts, but reality is more than facts. Reality is feelings and experiences and judgment and consequences. And those are things not so easily labeled as “non-fiction.”

The experience of reading The Things They Carried reminded me of reading Challenger Deep by Neal Shusterman. Challenger Deep won the 2015 National Book Award for Young People’s Literature, and it’s the story of teenager Caden Bosch’s descent into schizophrenia. It’s clever and engaging and terrifying. Although the book is fiction, Shusterman based it on his son’s experience battling mental illness.

Both O’Brien and Shusterman have messages to convey, but they deliberately use fictionalized stories instead of facts and data to do so. Basing their books on and in their experiences, they offer stories to their readers and ask them to consider the experiences of the characters before them – characters who are much more real than they might seem. The authors gain credibility and connect with readers in closer and more personal ways then they could by writing entirely fact-based accounts.

The context of a story or where it comes from doesn’t always matter. (I think it’s fair to say that knowing the idea for Twilight came to Stephenie Meyer in a dream isn’t likely to change one’s experience with the book.) But in cases like The Things They Carried or Challenger Deep, an author’s context and history can enhance the message in a story. Anchoring a tale in personal experiences offers readers a kind of truth that resonates more deeply than either fiction or non-fiction can do alone.