How Princess Mary’s Gift Book Sparked a Belief in the Existence of Fairies

Picture the scene: you are a weird little girl in the 1910s. The world is falling apart around you. There is little joy to be found when all the news is about the Great War. In 1920, Arthur Conan Doyle writes an article in The Strand magazine about two girls who successfully photographed fairies back in 1917. Sweet vindication washes over you before the eventual debunking. Before the photos were proven to be fake, the obsession over them and their supposed iron-clad proof of the existence of fairy life caused a major stir. The story is still fascinating because two young girls tricked the world with the enthusiastic assistance of Arthur Conan Doyle and the use of Princess Mary’s Gift Book.

The Hoax

In Fakers, Forgers & Phoneys: Famous Scams and Scamps, Magnus Magnusson documents the day of the fairy photos. Nine-year-old Frances Griffiths and her cousin, 16-year-old Elsie Wright, often played together in a small brook near their house in the Cottingley village in West Yorkshire.

They told their mothers that they had played with fairies and took Elise’s father Arthur’s camera to prove it. Arthur developed the photos but dismissed them as fakes because of his daughter’s keen artistic ability, but Elise’s mother, Polly, believed the photographs were real. The girls took a few more photos to prove it, but Arthur stopped lending his camera to them.

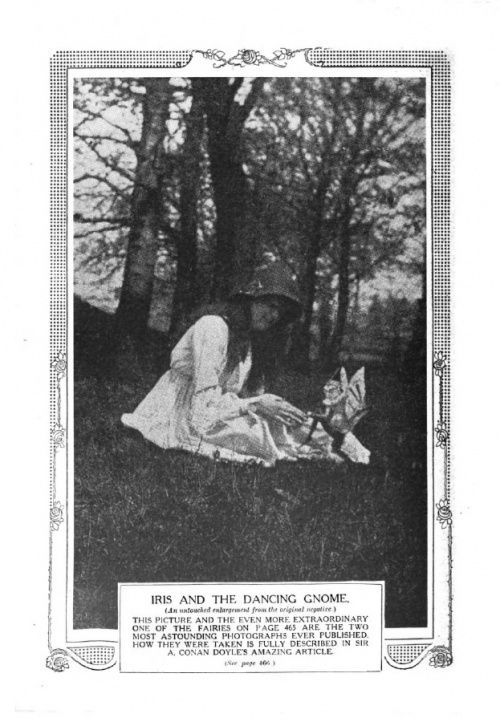

The most recognizable photo is one of Frances taken by Elsie, with realistic-looking fairies posed in front of Frances.

The Spread of the Photos

Before Arthur Conan Doyle got his hands on them, the photographs were circulating. Frances wrote a letter to a friend back in her home country of South Africa about what her life was like in England and enclosed a picture of herself with the fairies. She said that she never saw fairies in Africa, possibly because it was too hot.

In 1919, Polly Wright went to the Theosophical Society in Bradford for a lecture about fairy life. She then showed the photos to the speaker, and they were displayed at the society’s annual conference. Theosophy was a religion founded in the 19th century that focused on occultism, pulled together strands of Eastern philosophy, and general spiritualism. Followers of theosophy were very likely to believe in fairies, so the audience was an excellent place for spreading the story.

A high-ranking member of the society, Edward Gardner, gave a series of lectures on the photographs, and they caught the attention of Arthur Conan Doyle. He was in the process of researching an article about fairy life. Before publishing the photos in The Strand magazine, Conan Doyle had experts look at the photos, which he said proved that they were real.

Despite Arthur Conan Doyle’s most famous character being a figure of logic and reason and evidence, Doyle himself was much more interested in spiritualism because of personal tragedies: the loss of his son, his brother, and his brother-in-law during the Great War and the subsequent flu pandemic. Additionally, Arthur Conan Doyle is a great example of an author whose real-life personality has no correlation to his most famous character. During the years of the Cottingley fairies hoax, Doyle was still writing Sherlock Holmes stories, but he was also focusing on his work about spiritualism and the supernatural. At the time, he was working on his series, The Uncharted Coast, about ghosts, apparitions, et cetera.

Arthur Wright, Elise’s father, allowed Conan Doyle to use the photographs in his first article, “Fairies Photographed,” in The Strand. Frances and Elsie were renamed Alice and Iris to protect their anonymity for the time. The magazine sold out, and “fairy fever gripped the nation. Even those suspecting the girls of fakery couldn’t understand how they’d done it, or why. For many people, the simplest, and perhaps preferable, conclusion was that the fairies were, indeed, real. Improbable, yes. But not impossible.”

Since the world did not universally accept the existence of fairies, Edward Gardner visited Frances and Elsie and pushed for more photographs to be taken. They said the fairies would not reveal themselves to strangers, and they produced more photos on their own. Doyle published these photos in a follow-up article in The Strand in March 1921 called “The Evidence for Fairies.” The photos were still not universally accepted, with some noting that the fairies looked like “the traditional fairies of nursery tales.”

Edward Gardner visited Frances and Elise again in 1921, but by that time, they were a bit bored with the whole business and ready to move on. Arthur Conan Doyle used the photographs in his 1922 book The Coming of Fairies as incontrovertible proof of fairies.

Eventual Admission

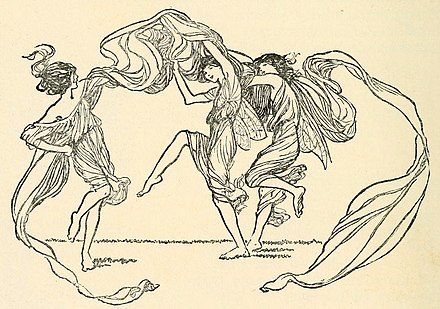

Though many believed the photos were real for decades, Elsie and Frances admitted in 1983 that it was a deception. Elsie, a keen artist (as her father knew), reproduced illustrations by Claude Arthur Shepperson of dancing girls from her copy of Princess Mary’s Gift Book and added wings to the drawings. They propped up the fairies with hatpins. They got rid of the drawings after the photos, so Arthur Wright’s assertion that he hadn’t found any evidence of a hoax was true when he said so in the past.

Princess Mary’s Gift Book was unexceptional in that it was common for English royals to create gift books to benefit their charitable organizations. Princess Mary’s book came out in 1914 and “contained a collection of children’s stories and illustrations by the leading authors and artists of the day, [it] was published to raise funds for The Queen’s Work for Women Fund (a subsidiary of the National Relief Fund, which raised money for several military and civilian charities during the war years). The fund, which was set up in August 1914, was intended to initiate and subsidise projects for employing women who were out of work as a result of the war.” The book itself is still sold by secondhand and rare books dealers, most likely because of its status due to its part in the Cottingley Fairies hoax.

The drawings on paper were part of what made the fairies appear so realistic in the photographs. The apparent movement was part of why so many experts believed the fairies to be real in the photos.

Elsie said the photos were fake, but Frances said one of the photos taken was real. On an episode of Arthur C. Clarke’s World of Strange Powers, Frances and Elsie gave interviews. Elsie said she didn’t want to admit they’d fooled Arthur Conon Doyle, while Frances opined that “they wanted to be taken in” by the trickery of the fairy photographs.

The Cottingley Legacy

The fairy photographs were never universally believed, but there were enough people bolstering the truth of the photos that they endured as an important curiosity for decades. After Frances and Elsie admitted to using illustrations from Princess Mary’s Gift Book, most people interested in the story focused on how someone like Arthur Conan Doyle fell into the hoax and was so steadfast in his belief.

It’s possible that, like Conan Doyle, many people were struggling with the after-effects of World War I and its emotional toll and therefore wanted to believe in something more magical. Also, at the time, the play Peter Pan, where the entire audience is encouraged to clap to affirm their belief in fairies, was still active on the West End and Broadway.

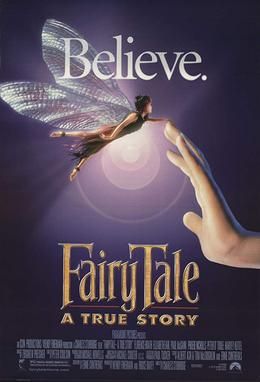

My introduction to the Cottingley Fairies hoax was the movie FairyTale: A True Story (1997, directed by Charles Sturridge) in the sci-fi/fantasy elective run by my coolest middle school teacher. The movie is fiction, of course, but calls itself the “true” story and asserts the fairies were real and acted as quasi-guardians for Frances and Elsie.

As far as the fairy photographs providing definitive scientific evidence of fairies, the story was a hoax. As far as reaffirming my belief that children can find magic anywhere they go, it’s undeniably true.

For more details, the podcasts Criminal and You’re Wrong About went deep on all the particulars of the Cottingley Fairies. If you’re interested in conspiracy theories, you can read about literary hoaxes or dive into books about conspiracy theories.