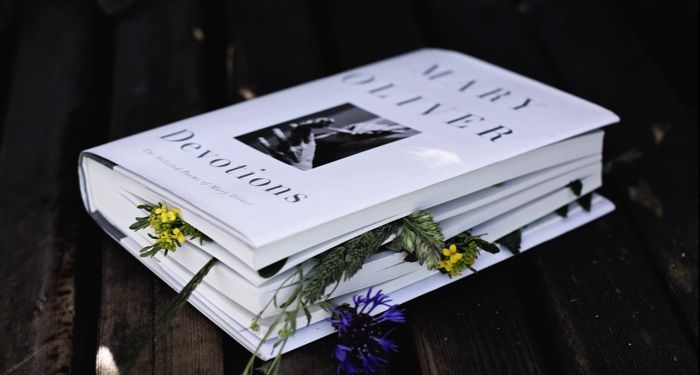

Mary Oliver’s Poetry: Reading Her in the Worst of Times

Last year, around May, my country was badly hit by the second wave. Every morning brought bad news of one kind or another. Staying awake became a harrowing experience in itself as it meant receiving news of the deaths of someone I loved or had loved at some point. Deaths that could have been avoided if our government was proactive enough to provide adequate medical care instead of wasting money on organizing campaigns and election rallies, and other kinds of tomfoolery characteristic of those whose megalomania ru(i)ns countries. Taking a day off from the humanitarian crisis unfolding in India was not an option for any of us. Not knowing how to be useful in a dying world, I looked to Mary Oliver’s poetry for answers.

I have never bought into the idea that loved ones become stars after their death. Stars too are mortal. If it was on me I would have turned them into ether, the negative blank space where stars float around. Unlike stars, ether lasts for an eternity. In the poem ‘In Blackwater Woods’, Oliver writes, “To live in this world / you must be able / to do three things / to love what is mortal; to hold it / against your bones knowing / your own life depends on it; and, when the time comes to let it go.” Oliver urges us to never make the mistake of passing up on a chance at love or holding on too tight when its time comes to an end. Our loved ones might be stars but what we shared with them is ether. Memories outlast time and times when the world seems like a place that doesn’t tolerate joy, revisiting them will keep you striving for life.

The more dramatic our government grew in its apathy towards the suffering of its people, the more Indians resorted to social media to extend whatever resources they had to those in need. In her book Evidence: Poems, Oliver says, “I believe in kindness. Also in mischief. Also in singing, especially when singing is not necessarily prescribed.” Even though we were nowhere close to being able to appreciate music again, the collective kindness of strangers felt like hope. It seemed like the entire country was living by Oliver’s mantra — “Love yourself. Then forget it. Then, love the world.” India was going through a melancholic sort of hypnosis, the kind where you are pulled into relieving days you wish you never had to live in the first place. But reading Evidence: Poems made me believe, and quite strongly at that, that hope, in all its shapes and sizes, was just around the corner waiting for us to find it. And goodness didn’t need to be rationed as it is never in limited supply. Who knows, maybe someday we’ll be allowed glimpses into a world where animosity and foreboding don’t exist at all!

Regardless of how hard we tried, tragedies dropped into our world constantly. But despite that, I found joy in a “you doing okay? hit me up if you need anything” text of a long-lost friend. Joy was also there in watching from my bedroom window lockdown babies growing up into fully-fledged toddlers on my neighbor’s terrace, on a particularly bright sunlit afternoon. Was I delusional to still have faith in the world? To feel that our everydays will never not be full of constant reminders of life? I picked up Oliver’s Swans: Poems And Prose Poems and coincidentally she had an answer, ending my quandaries once and for all. She says:

If you suddenly and unexpectedly feel joy, don’t hesitate. Give in to it. There are plenty of lives and whole towns destroyed or about to be. We are not wise, and not very often kind. And much can never be redeemed. Still life has some possibility left.

Those of us who survived the second wave will forever carry the aftermath of a genocide within us. It won’t be called a ‘genocide’ by history because history is not what happens but who gets to tell the story. However, there’s still hope in knowing that having not died together, maybe we will live together. Long enough to ‘think again of dangerous and noble things’ and ‘be light and frolicsome’. And definitely long enough to ‘be improbable beautiful and afraid of nothing’, as if we ‘had wings’.