5 Incisive Dystopian Books on the Economy and Work Culture

When I read Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World in high school, I hated it. Absolutely detested it. The writing, the world, the characters, the ending. All of it. I had loved Thomas More’s Utopia, Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland, and George Orwell’s 1984. Years later, I have come to realize that I hated it because it scared me. Elements of it seemed so much more plausible than the other books. And I was reacting against that. Its view of the economy and society seemed too on the nose for me.

But in recent years, I’ve encountered several books that present other economic and cultural commentary that is just as disquieting as Brave New World. With the recent events with GameSpot and the Stock Market, critiques of economic systems seem even more salient.

Here’s my list of five dystopias that provide incisive economic and political critiques. Two books seem like the children of Brave New World, presenting futures based on consumption gone wild. The other three present critiques of work and bureaucracy.

Qualityland by Marc-Uwe Kling

Imagine a world where algorithms form the structure of society. Your ability to get jobs, find a romantic partner, your friends are based on your “number.” It’s a world where “The Store,” an Amazon-like company, anticipates your needs and wants and sends you products without you having to order them. Plus everyone’s surname is derived from their father or mother, depending on their gender. That’s the world that Peter Jobless is living in. He fixes “useless” robots, but when his score dips below 10 (on a scale from 1 to 100), his life starts to get a lot more difficult. When he receives an item he categorically does not want, he goes on a mission to return the item to The Store. It’s an incisive commentary on a world reliant on algorithms and social points as the organizing principle. Here’s my full review at Broad Street Review.

The Queue by Basma Abdel Aziz

After a failed uprising known as the “Disgraceful Events,” the State has mandated that everyone must appeal to the Gate for any and all matters. A queue begins to form of people trying to get help with health care, housing, and more. But the Gate never opens, so the line just gets longer and longer. When Yehia gets shot for being in the wrong place at the wrong time, he cannot get the bullet removed because as far as the State is concerned, there are no bullets. So Yenia gets in line to appeal to the State. The Queue is a scathing indictment of the bureaucratic and oppressive state.

The Resisters by Gish Jen

Gish Jen envisions a world organized based on production and consumption. In AutoAmerica, the Netted produce and get all the advantages of life — living on dry land, university, and more. The Surplus live on swampland (or worse water) and are expected to consume and gain points for more consumption. And the split “happens” to be on racial lines. Homes are equipped with Aunt Nettie, an Alexa on steroids, that monitors all. The story focuses on a Surplus family: Grant, a former professor; Eleanor, a still-practicing lawyer; and their daughter Gwen, with the golden arm. When her pitching talent is recognized, she gets recruited for the Olympics and enrolled in Net University. It’s a story of parents having to learn to let their daughter make mistakes away from home. It’s about generational conflicts and resistance — Gwen wants to benefit from high society as her mother has made a career (and life) of fighting against the segregation and oppression of society.

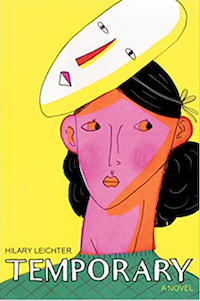

Temporary by Hilary Leichter

Temporary envisions a world where jobs become our identity. So if you are a temporary worker, like the unnamed narrator, you are constantly jumping from job to job, changing yourself completely. The narrator finds herself in a variety of jobs, from window cleaner, assassin’s assistant, and even mother, in the search for Steadiness. She learns to smoke for one job, knowing she’ll have to unlearn it for another. It’s a commentary on gig culture and the role of women in U.S. working society.

The Factory by Hiroko Oyamada, Translated by David Boyd

The Factory presents a critique of our collective working lives. Three workers in a factory in an unnamed Japanese city have very specialized jobs: one proofreads, one studies moss, and one shreds things. Soon their seemingly pointless jobs become more than just jobs as the factory expands and becomes all-consuming. Where does work and where does other life occur?

Want more dystopias? Check out this Rioter list of Eco-Dystopias or this Rioter list of Timely Dystopias.