Captain America, Japanese Internment, and the Illusion of Good Intentions

In a recent plotline in Friendly Neighborhood Spider-Man by Tom Taylor and Juan Cabal, Peter Parker teams up with his friend’s elderly neighbor Marnie—AKA the X-ray-visioned superhero The Rumor—to take down some corporate evildoers. In issue #9, Marnie shares that she’s even older than she looks—she immigrated to the U.S. from Japan in the late 30s, and was interned along with other citizens and immigrants of Japanese descent from 1943–1945, despite having fought Nazis alongside Captain America in the earlier years of the war.

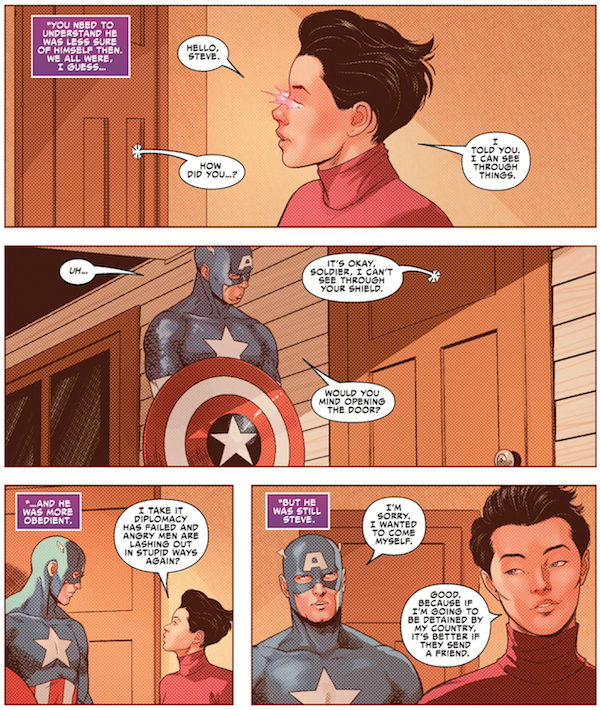

In a flashback that’s caused a bit of a stir on Twitter, Marnie reveals that it was Captain America himself who came to take her to the internment camp. Head hanging, he offers useless apologies for the thing he is doing:

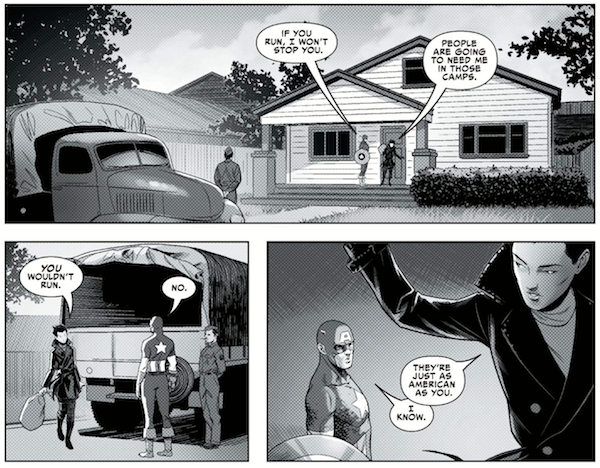

On the next page, he makes a faint attempt at non-compliance by offering her the chance to run and promising not to stop her:

This is a hollow offer, and Marnie knows it. First of all, he makes it clear that he would consider running wrong if he were in her place—an easy rhetorical position to take when by virtue of his privilege, he will never be in her place. (Don’t @ me about Civil War, which is a garbled metaphor at best and we all know it.) Second, if she did run and he was directly ordered to bring her in, would he resist, after complying with the initial order to take her to the camp? Third, if she did escape, what kind of life would she have as a fugitive? Finally, he agrees with her that the interned people, herself included, are just as American as he is—but it doesn’t change his actions.

This is not good Captain America writing.

Steve Rogers is not a perfect person, and he’s not meant to be. But he’s meant to be a good person, one who represents the potential of a country founded on lofty ideals that it so often fails to live up to.

To portray Steve Rogers as complicit in government-mandated, racially motivated human rights violations is not just out of character. It feeds into the easy narrative that “everyone went along with it in those days,” for a wide variety of what “it” might be. Internment camps? Segregation and lynching? Turning Jewish refugees away at the border? Sexism and homophobia? It was just Like That back then! No one knew any better!

This narrative is so common we barely even notice it anymore, but it does two very neat rhetorical tricks. First, it erases the existence of the marginalized in history. “Everyone thought the Japanese were spies back then.” Hmm, well, no—probably Japanese Americans didn’t!

Second, it frames positive social change as sudden, complete, and bequeathed upon us by unnamed, possibly divine forces. Everyone was racist, and the the Civil Rights Movement happened, and then racism was over. Everyone was sexist, and then the Women’s Lib Movement happened, and then sexism was over.

Except everyone wasn’t racist/sexist/[insert your bigotry of choice here], and social change is not everyone suddenly waking up wiser, but brought about by long, collective effort by people fighting against what they know to be wrong—effort that continues today. Injustice can only be fought when the people living inside unjust structures recognize them to be unjust, and take action.

In other words, it makes no sense to say “everyone thought that way back then,” because if some people hadn’t thought otherwise, nothing would ever have changed.

Obviously many white people were convinced that Japanese internment was a good idea, but there were plenty of white people who knew better. Some of them spoke out. There is documented opposition from government officials, in newspaper editorials, in everyday writing.

Steve Rogers should have been one of these opponents. It is a defining aspect of his character to oppose American policies when they conflict with American ideals.

To position Steve Rogers, of all characters, as someone who not only went along with internment but was actively complicit in it implies that it is possible to not only witness but take an active part in injustice that doesn’t personally affect you, and still be a good person. That it is enough to say “If you run, I won’t stop you” when you know that running is no real choice at all.

It is not. You cannot imprison your fellow human beings because of nothing but their race and be a good person. You know better. We have always all known better.

Americans today live in a world where our government is once again interning human beings—including children—because of their race and nations of origin. Our country is subjecting desperate people to innumerable human rights violations because of bigotry and fear. And once again, you cannot be a good person if you are complicit in this, even if you feel bad about it. Even if you’re really polite about it.

It’s clear Taylor knows this and is trying to make a point about it. In a very unsubtle panel, present-day Marnie sips a cup of tea and says: “Can you imagine? People incarcerated by the country they called home, purely because of where they were born, or where their parents came from, or even their grandparents?” You know, just in case you didn’t get the message.

I like Taylor’s work a lot, and Friendly Neighborhood Spider-Man #9 is, with the exception of two pages, an excellent comic book. (There’s an exchange where Iron Man tells Peter he leaves a residue behind when he wall-crawls and sends Peter into a tailspin of insecurity that made me laugh out loud.) Marnie is a fantastic character. And it’s very, very clear that Taylor’s trying to highlight our current human rights crisis by pairing it with a historical one. I absolutely get where he’s coming from.

But using Steve Rogers to illustrate the point in this way was a mistake, because it allows heroism and complicity to exist within the same person at the same time. It’s a tempting idea—it would be so much easier. But we have to resist it.

Captain America has always reflected not who we are, but who we should be, from his very first Hitler-punching appearance. He should never have been complicit in Japanese internment, any more than he should be complicit in immigrant detention now.

And if we don’t want our grandchildren to look back at us with shame, it’s time for us to start living up to those ideals too.

Further Reading: George Takei’s They Called Us Enemy (with Justin Eisinger, Steven Scott, and Harmony Becker) is a graphic memoir of his childhood experience of being interned and is highly recommended.