13 Women Writers Who Deserve Their Own Biopics

There’s something about the immediacy of watching historical events unfold onscreen that makes me all the more interested in learning about the real-life events. The subjects for this type of film—like the heroes of most films and TV shows—are most often white men. Keira Knightley’s upcoming film Colette examines the life of a woman writer, as did this year’s Elle Fanning vehicle Mary Shelley. Other (mostly white) women authors given the biopic treatment have included Jane Austen, the Brontë sisters, Emily Dickinson, Sylvia Plath, and Virginia Woolf. The number of films focusing on white male writers is too long to be listed here.

So, for any film executives looking for new subjects to focus on, here are our suggestions to diversity the genre of literary biopic. It just so happens this list of authors may also help educators wanting to diversify the works assigned to their students, and may help readers who (like me!) are always on the lookout for new authors whose works to read.

Louisa May Alcott

Why her life would make a great biopic: Louisa’s parents were transcendentalists and she spent part of her childhood living in a community called the Utopian Fruitlands, along with others sharing their beliefs of “plain living and high thinking.” The Alcott family served as station masters on the Underground Railroad, housing a fugitive slave for one week. She served as a nurse for the Union soldiers during the American Civil War. She was uncomfortable with the success of Little Women, and was known to masquerade as a servant in her own home when fans visited in hopes of meeting her.

Aphra Behn

Why her life would make a great biopic: Behn was working as a playwright when King Charles II recruited her to serve as a spy for him in the Netherlands in 1665. But as spy work didn’t pay well, she turned to playwriting as a career, becoming the first Englishwoman to make a living as an author. She was known to use the pseudonym “Astrea,” which had also been her codename during her days as a spy. Being a woman author caused some audiences to riot in protest, but she was not deterred and, in fact, included taboo subjects like male impotence and female sexual desire in her works.

Nellie Bly

Why her life would make a great biopic: She got her first job as a journalist after writing a letter to the editor criticizing misogyny in an article, then got her first major job as a reporter by going undercover to expose corruption at a women’s psychiatric hospital, then became the first person to travel around the world in less than 80 days, then quit her newspaper job when she didn’t get a raise for single-handedly inventing stunt journalism, then travelled the country selling her memoirs and giving speaking engagements. There are enough captivating stories that even a miniseries may not be enough time to cover it all.

Agatha Christie

Why her life would make a great biopic: Christie famously went missing for eleven days in 1926. She eventually turned up in a party down, where she’d been living in a hotel under a fake name and attending parties and balls for the whole time. And how was she found? By a banjo player at one of the parties, who recognized her as the missing author. Christie didn’t remember going there or what had happened, and later investigations hinted that she may have suffered traumatic amnesia following a car crash.

Radclyffe Hall

Why her life would make a great biopic: When Hall was 27, she fell in love with a 51-year-old singer named Mabel Batten. It was from Batten that Hall was given her lifelong nickname of John. Hall then fell for Batten’s cousin, with whom the author continued a lifelong affair even as she partook in affairs with other women—much to her partner’s chagrin. Her biographical fiction novel The Well of Loneliness was the subject of an obscenity trial in the UK, which resulted in all copies of the book ordered destroyed.

Patricia Highsmith

Why her life would make a great biopic: Highsmith famously preferred the company of animals to that of people and was known to have bred about three hundred snails in her home garden. She once attended a cocktail party with about a hundred snails in a handbag, which she explained were her companions for the event. She lived with depression and, in order to fund her twice-a-week therapy sessions, took a sales job at Christmastime at the toy section of Bloomingdale’s department store—a task which inspired her novel The Price of Salt, later adapted into the film Carol.

Harriet Ann Jacobs

Why her life would make a great biopic: Jacobs, born into Slavery in 1813, evaded her owner’s sexual advances by engaging in a consensual affair with a white lawyer. The couple’s two mixed-race children were enslaved to her owner as well, and although the owner threatened to sell them if Jacobs did not succumb to his sexual advances, she continued to evade him. In 1835, Jacobs escaped, initially hiding in a nearby home to keep an eye on her children. She lived in hiding for seven years in her grandmother’s attic, including a period of time in which her children lived in the house and she was only able to catch glimpses of them and hear their voices. In 1842, Jacobs escaped to Philadelphia and later New York, where she was able to reunite with her daughter and later her son. Upon encouragement from Harriet Beecher Stowe, Jacobs began work on her autobiography, working secretly at night.

Elizabeth Keckley

Why her life would make a great biopic: Keckley, born a slave, was freed in 1852. In 1860, she moved to Washington, D.C., with hopes of working as a seamstress. A dress she made for Mrs. Robert E. Lee brought her to prominence, and word of mouth recommendations built her business of making gowns for society women. She was lated chosen to be the personal modiste for the fashion-loving Mary Todd Lincoln, for whom Keckley also worked as personal dresser. Following the assassination of Lincoln’s husband, Keckley accompanied the President’s widow as she embarked upon her new life in Chicago. The women’s friendship was strained after Keckley donated her Lincoln memorabilia to a fundraiser for Wilberforce College. Keckley’s memoir included letters she had received from Lincoln, and was criticized at the time for its sometimes unflattering portrayal of white women.

Jean Rhys

Why her life would make a great biopic: Rhys was born Ella Williams in the British West Indies to a Welsh father and a Scottish mother. At age 16, Rhys was sent to England, where she was ostracized by schoolmates for her accent. She worked as a chorus girl, then became mistress of a wealthy stockbroker who refused to marry her. Following a near-fatal abortion, she found work as a nude model. During World War One, she volunteered to work in a soldier’s canteen. She married three times, and the third of her husbands was imprisoned for fraud.

George Sand

Why her life would make a great biopic: Born Amantine-Lucile-Aurore Dupin, Sand was a distant descendant of French royalty and a baroness in her own right. Raised by her mother, a sex worker, and her grandmother, an aristocrat, Sand was briefly married at age 18 before embarking on a series of notorious love affairs with both men and women. Sand supported the poor and working class, supporting the insurgents during the 1848 revolution, during which she started her own newspaper. She was known for wearing men’s clothing, which she felt were more sturdy and less expensive than women’s garments, as well as for smoking cigars. As a consequence of her non-traditional behaviour, Sand was obliged to relinquish some of the privileges of being a baroness.

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Why her life would make a great biopic: Harriet was the seventh child born into a family of thirteen children. She attended a seminary run by her older sister, receiving the type of academic education usually only reserved for men. She and her husband were both ardent critics of slavery, and housed fugitive slaves in their home as part of the Underground Railroad. After having a vision of a dying slave during a church service, Stowe was moved to write this man’s story. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published as a newspaper serial beginning in 1851 and, due to its unprecedented popularity, was later published in book form. In her later years, following the death of her husband, Stowe began writing Uncle Tom’s Cabin again—imagining she was reliving the initial writing, living back in the time of its original writing.

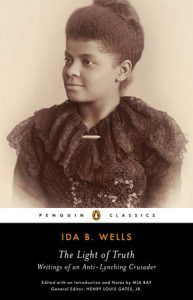

Ida B. Wells

Why her life would make a great biopic: Wells was an investigative journalist, educator, an early leader in the Civil Rights Movement, and one of the founders of the NAACP. Born into slavery, Wells was freed but lost both her parents to illness when she was 16 years old. She worked as a teacher, then became co-owner of a newspaper. She used her platform to document lynching in reported pieces that were carried nationwide in black newspapers. Subjected to continuing threats and attacks, including the destruction of her newspaper presses, Wells moved to Chicago where she married and had a family. She continued to write, speak, and organize for civil rights throughout her life.

Mary Wollstonecraft

Why her life would make a great biopic: the mother of Mary Shelley, Wollstonecraft was an English writer, philosopher, and advocate of women’s rights. She was romantically involved with the married artist Henry Fuseli and proposed a platonic living arrangement with him and his wife; when his wife was appalled by the suggestion, Wollstonecraft and Fuseli ended their relationship. She fled to France to participate in the French Revolution, where she spent time with other English expatriates and witnessed the beheading of Louis XIV. While there, she became involved with the American adventurer Gilbert Imlay. As the Reign of Terror began in France, Wollstonecraft fell under suspicion as an English subject and many of her friends were guillotined. Imlay left her after the birth of their daughter, and she followed him back to England, desperate to reunite. She attempted to drown herself in the River Thames but was rescued by an onlooker. She later fell in love with philosopher William Godwin, who she married in order to legitimize their daughter, Mary. Wollstonecraft died days after Mary was born, due to complications of childbirth.

RELATED: 100 Must-Read Classics By Women