Three Williams: My Life With a Trio of Dead Poets

This is a guest post by Rosie Schaap. She has been a bartender, a fortuneteller, a librarian at a paranormal society, an English teacher, an editor, a preacher, a community organizer, and a manager of homeless shelters. A contributor to This American Life and npr.org, she writes the monthly “Drink” column for The New York Times Magazine. Her memoir, Drinking With Men, has just been published by Riverhead Books. Follow her on Twitter @rosieschaap.

_________________________

In his preface to Lyrical Ballads, William Wordsworth wrote that “poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility.” Now, after many years have passed, in a moment of relative tranquility, I can say that in college I was a complete, poetry-addled dork. And confess that I still am.

In my memoir, Drinking With Men, I mention my habit of pacing my college campus reciting William Butler Yeats’s poems to no one in particular. My interest in all things Irish, coupled with a weakness for weirdo mysticism, made him irresistible. I tried not to think too hard about his crackpot notions about gyres and historical cycles, or about his politics: Nationalistic, sometimes downright Fascist, tinged with the noxious odor of aristocratic entitlement. But I was powerless before the gorgeousness of phrases like “cold companionable streams,” the seductiveness of “The Hosting of the Sidhe,” the confessional reckoning of “the Circus Animals’ Desertion.”

I came to William Blake backwards through Yeats, who was a great admirer, and misreader, of the earlier poet. In Blake I saw a model of a radically imaginative way of thinking, of a kind of creative indignation that made whatever indignation already burning in me give off more light, and a trellis upon which to train my strong, strange religious impulses. “What,” it will be Question’d, “When the Sun rises, do you not see a round disk of fire somewhat like a Guinea?” O no, no, I see an Innumerable company of the Heavenly host crying, `Holy, Holy, Holy is the Lord God Almighty.’ This passage from A Vision of the Last Judgment made perfect sense to me then, and still does.

But it’s Wordsworth who almost really got me into trouble. There was a small lake near campus, and I thought it best to go there to read greatest “Lake Poet,” you know, beside a lake. My preferred mode of dress was one I might describe as Amish meets Whistler’s Mother—heavy on charcoal gray and brown and black. Not long after I opened up The Prelude, I heard strange noises coming from the nearby woods. I hadn’t known was the first day of hunting season—and it occurred to me that, from afar, I might not implausibly be mistaken for a deer. I tore back down the road and took refuge in the general store. “Yup,” the knowing Vermonter behind the register nodded. “Best wear something orange instead.” Obviously, it’s not Wordsworth’s fault that I might’ve gotten myself hurt that day. It was my own misguided impulse to immerse myself in his world in the most literal way I could find.

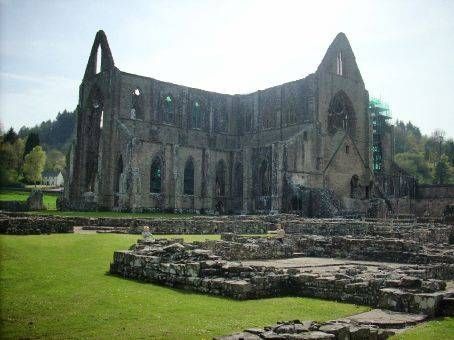

All three Williams turn up in Drinking With Men. It’s Wordsworth to whom I turn most often. His ode on Tintern Abbey is my desert-island poem. When I feel disconnected from the people I love, or otherwise troubled, it’s what I need to reconnect me. Wordsworth announces this power in the poem itself: “If solitude, or fear, or pain, or grief,/Should be thy portion, with what healing thoughts/Of tender joy wilt thou remember me/And these my exhortations!” Writing out those lines makes me want to read the poem again. Right now.