Saadat Hasan Manto’s Legacy: On Reading Manto In A Crumbling Nation

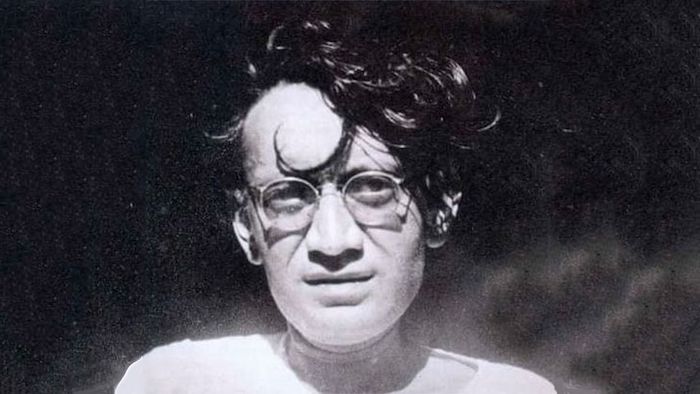

Saadat Hasan Manto, born in Ludhiana of British India, in 1912, was a prolific writer and playwright. Hailing from complicated family background, Manto has always had a rebellious streak to him that is very prominent in his work. He loved alcohol and died in his early 40s. Over the course of his short life, he had produced 20+ collections of short stories, a novel, radio plays, and essays. He was a nonconformist and his work bears testimony to that.

Manto mainly wrote in Urdu and his fiction is powerful, gut-wrenching, extremely thought-provoking, and defies the status quo. He is best known for his stories on the Partition of India and how it brought out the worst side of humanity. His work is in ways autobiographical and does portray his divided self. Manto was tried for obscenity multiple times but that didn’t deter him from speaking up about the cold, hard reality that was foisted on the populace and calling out those in power. Personally speaking, reading Manto’s work in India’s current sociopolitical landscape has taught me that no authority has the right to make demands of me that run in opposition to my identity.

In his story, “Mishtake” (originally titled “Sorry” in Urdu), which is about the length of a paragraph, Manto describes a man killing another. A knife was being swished through his belly. As the knife landed under the navel and cut down the other man’s trousers, the killer realized that he had made a mistake. During the Partition riots of 1947, when communal hatred was on the rise, whether a man was a Muslim or a Hindu was determined by his penis. Traditionally, Muslim men unlike Hindu men go through the process of circumcision at birth. Circumcision determined who would live and who had to die.

In a few graphic lines, Manto had captured how the Partition of India became the yeast for heartbreaks and divisive politics. Even though India is a land of many religions, the conflict between the Hindus and the Muslims that started with the Partition of India, rears its ugly heads every now and then.

Very recently, Muslim girls at a college in Karnataka (a state in India) were held back from entering their classrooms as they were wearing hijab. Anti-hijab protestors are backed by the right-wing government. Years after Partition, the Indian society is still rooted in caste, class, and religious prejudices. For someone who comes from a lower caste background like me, navigating this world is often harrowing. Minority communities are constantly pushed to the fringes.

Manto’s India is not much different from current India as the movers and shakers of our society are still bent on wrecking the world before the commoners can even taste it. People like me lead chants and shake fists, but some force much bigger than us turns our friends into foes, as we see in “A Tale Of 1947.” In this short story, we see friends casually talking about murdering one another. This story stresses how friendships are bound to shatter under the influence of religious and political hatred.

The making of the nation demands we create a divide between the self and the other. The concept of the nation is ambiguous and it promotes a sense of belonging that inevitably borders on alienation. In his short story, “Toba Tek Singh,” Manto focuses on the inmates of “the lunatic asylum at Lahore.” The image of the asylum is a metaphor for the chaos and distress that followed the Partition of India. The main character, Bishan Singh, is collateral damage, if we keep the grander scheme of things in mind. He is the mouthpiece of the pain and trauma of displacement.

Years after the Partition, India and Pakistan are still grappling with its madness. The territorial conflict over the Jammu and Kashmir region, primarily between India and Pakistan, is never-ending and has been disrupting the peace and security of Kashmiri civilians. The common people have been going through brutality of every kind because of political agendas that are far removed from their wellbeing. Manto’s Bishan Singh stood between the borders of both the countries and claimed this nameless land as his place of belonging. The induced violence and loss of psychological equilibrium are patterns that keep repeating themselves. Much like Bishan Singh, the hoi polloi of contemporary India and Pakistan is falling apart. They are being dehumanized constantly just so governments can benefit from their trauma and loss.

Despite all the doom and gloom, there’s still hope. Recently, a video surfaced on social media of two brothers separated during the Partition, reuniting after 74 years! The political powers might always try to reduce our neighborhoods to rubble and turn us into statues in perpetual surrender like Manto predicted. But no force can ever scrub our identities in their entirety.

Humanity will persist because there are always going to be writers like Manto who capture the gore and savagery of the world through their words, to warn us to do better by ourselves as well as others: to make better use of our one wild and precious life!