MARBLES and My Own Mental Illness

We here at Panels are taking some much needed time off; in the meantime, we’re revisiting some favorite old posts from the last 6 months! We’ll see you back on July 11 with all new posts for your enjoyment.

This post originally ran on May 4, 2016.

_______________

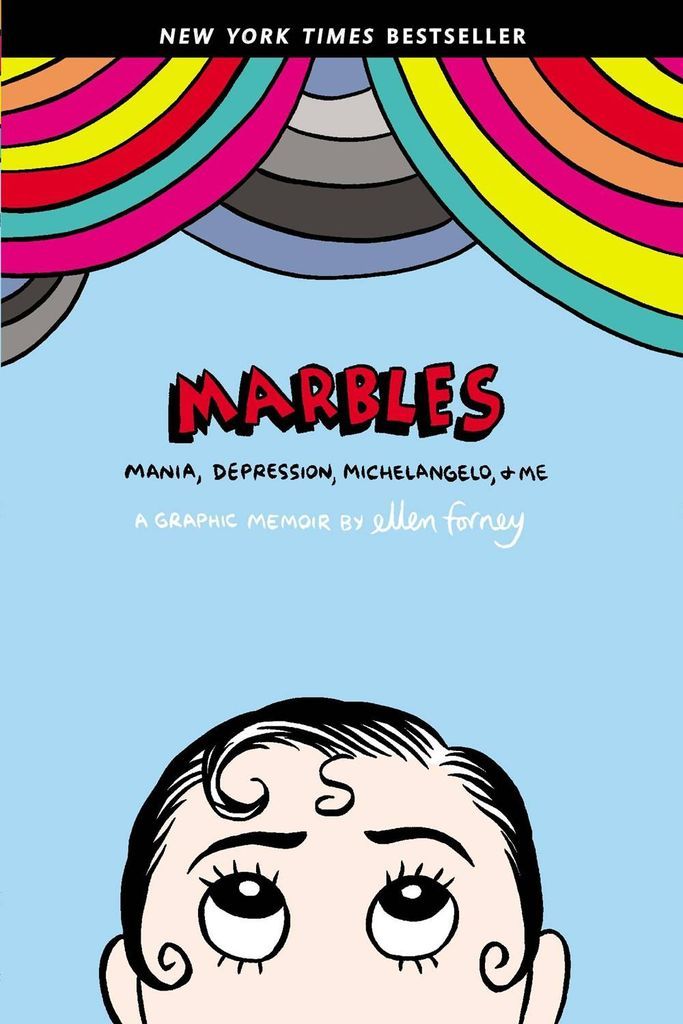

It took me three years to read Ellen Forney’s Marbles: Mania, Depression, Michelangelo, and Me. Not because I didn’t have the time, or the interest, or the money, but rather: I also struggle with mental illness, and I can only read about it when I’m in the right frame of mind. Nonfiction is often too clinical; memoirs are wrenching; fiction may stumble over the details. But despite the pitfalls, I’m drawn to the tangible evidence that other people are also secretly fighting, that their illness is powerful enough to write about.

Reading Marbles, I’m introduced to Ellen during a manic period, when life is vibrant and fearless, the art unrestrained by traditional comic panels and bursting with stars and flowers and movement. I feel jealous. This is the kind of person I want to be, the kind that depression usually keeps me from being: social and adventurous, overflowing with creativity. (There are warning signs, of course: Ellen is a reckless spender, enthusiastic to an overbearing degree – but I, like Ellen, ignore them.) Ellen is at first reluctant to see her bipolar disorder as a disorder at all; to her, it’s what fuels her art. Besides, lithium makes her break out.

Then she slides into depression. The art becomes simple, almost formless – a small blob of a human struggling to rise from a mound of blankets. For weeks she creates nothing. Eventually she is forced to admit that trying new medication might help her. This is the part of the story that makes me recoil in recognition. But for the grace of doctors, that would be me. Might still be me in the future.

In an attempt to understand how her mental illness may be tied to her creativity, Ellen researches famous sufferers like Vincent van Gogh and Virginia Woolf. I resist the “crazy artist” stereotype because it doesn’t match my experience (my mental illness stoppers creative energy) and because I think it discourages creative sufferers from seeking help (see here: Ellen’s initial view of medication as antithetical to “authentic” creativity) – but I can’t fully deny the pull of that narrative, the idea that maybe nature has given a gift to balance out a curse. Ellen doesn’t find a definitive answer, but she does find a sense of community in the life stories of other mentally ill artists.

And, ultimately, that’s what Marbles gives me: a kind of sisterhood. An understanding. A reassurance.

It takes Ellen over four years to find the best combination of medications, therapy, and lifestyle changes to manage her bipolar disorder. She’s not cured – there is no cure, for her or for me – but she’s getting out of bed. She’s able to look herself in the mirror and say, “I’m okay!” And she’s making comics, both despite and because of her illness.