If Books Were Bands

Sometimes, late at night, as I’m trying to get to sleep, I’ll torpedo the whole attempt by asking myself life’s grand questions, like, if Radiohead were a book, which book would they be? After some deep thought (and a couple of Sennheiser-aided marathon listening sessions), I’ve thankfully found the answer to that question and a few more like it. If books were bands (or solo artists; I’m not picky), then:

I’m not starting with much of a stretch, I’ll grant you, but Steinbeck’s Pulitzer-winning tome and The Boss go together like a dusty, world-weary PB & J. The most obvious connection is Springsteen’s 1995 acoustic album The Ghost of Tom Joad (sample lyric: Got a one-way ticket to the promised land / You got a hole in your belly and gun in your hand / Sleeping on a pillow of solid rock / Bathin’ in the city aqueduct), but from the start (1973’s The Wild, The Innocent & The E Street Shuffle) Bruce has been singing us stories about scrappy, hard-luck youths from the wrong side of the tracks just tryin’ to find a way to get by. Steinbeck’s work, and TGoW especially, mirror Springsteen’s concern for the marginalized and his ultimately hopeful view of America’s moral resolve.

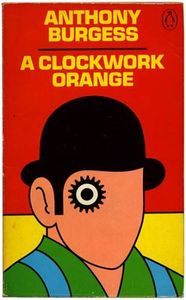

A Clockwork Orange would be Radiohead

Frightening, subversive, paranoid, and at times a real challenge to parse. Check, check, check, and check. Anthony Burgess’ classic satire and nearly all of Radiohead’s catalog (especially from Kid A forward) grapple with the dark realities of sweeping institutional (be the institutions corporate, financial, governmental, religious, or social) power and corruption, especially its deleterious effects upon individual consciences. The electronic shudders and starts of Radiohead’s second act have always seemed beamed in from some dystopian future, probably one where the “kicking, screaming, Gucci little piggy” from “Paranoid Android” is seated at the Korova Milkbar, being eyed lustily by Alex and his droogs.

Think about Whitman’s most famous line: “Do I contradict myself? Very well then…. I contradict myself; I am large…. I contain multitudes.” Has there ever been a better description for Bob Dylan? No musician has worn as many hats with as much success as Mr. Zimmerman: smart-ass folkie, beleaguered troubadour, country crooner, Born-Again proselytizer, blues revivalist. Both Blonde on Blonde and Leaves of Grass feel like the records of men on impossible missions, trying to capture the essence of humanity’s endless mysteries, one abstract impression at a time. The shambolic visions of America’s poet and America’s songwriter (sorry, Michael Bolton fans) have long captured the minds of readers and listeners, leaving them equally satisfied and mystified.

Flannery O’ Connor’s first novel centers on a drifter named Haze Motes, who spends most of his time chasing jailbait and attempting to start the world’s first Church Without Christ. However, no matter how far from his family’s preaching roots Motes runs, he is continuously defined by his bitter relationship with the God he attempts to excise from his life altogether. Two years ago, Bazan, whose group Pedro the Lion served as an outlet for gritty depictions of his own struggles with faith and Christian attitudes before he went solo and became agnostic, released Strange Negotiations, a caustic record detailing his religious change of heart. Just like Haze, however, Bazan seems doomed to grudgingly acknowledge the God he rejects and navigate the world as a battered congregant in his own personal church.

The best of Greene’s Catholic novels, The End of the Affair is as melancholy as Morrissey (which is saying something). Bendrix, the book’s narrator, agonizes over the abrupt end of his relationship with the wife of an acquaintance, feels hard done by, and demands an explanation for what he sees as her random act of cruelty. Greene’s mopey, sex-obsessed, solipsistic narrator is a perfect match for the woe-is-me types that populates many of the Manchester band’s biggest hits. What permeates both the novel and The Smiths’ oeuvre most completely, though, is a ragged insistence that no one else understands just how bleak the world really is. The bartender who finds Bendrix and the narrator of “Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now” drowning their sorrows together is in for a long dark night.

Did I get these right, readers? Have you already come up with one (or seventeen) of your own book-band connections? Let’s hear ’em.