In Defense of Cowardly Protagonists

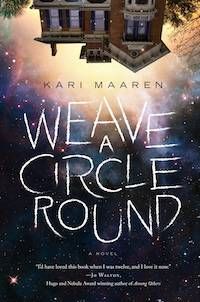

This is a guest post from Kari Maaren. Kari is a Toronto-area writer, award-winning musician and cartoonist, and academic. She created the webcomics West of Bathurst and It Never Rains, and is also known as a musician for her popular song “Beowulf Pulled Off My Arm.” Weave a Circle Round is her first novel.

In Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time, as Meg Murry prepares to go with her brother Charles Wallace and her friend Calvin to rescue her father on Camazotz, their three mystical guides give them gifts to help them along. To Meg’s puzzlement, Mrs. Whatsit gives her her faults. At first, she doesn’t understand; isn’t she always trying to get rid of her faults? As the plot progresses, however, it becomes clear that Meg’s faults—particularly stubbornness, quickness to anger, a tendency to blame everyone but herself, and the refusal to give up even in the face of impossible odds—are also her strengths. The qualities society is always trying to beat out of her are the qualities that ultimately allow her to defeat the evil IT.

This passage has had a profound effect on my own writing. I often think of my characters in terms of their faults: not superficial flaws, but deeply rooted issues that most people would label defects. I’d thus like to take this opportunity to discuss what is, to me, one of the most interesting character “faults”: cowardice.

Cowardice is a useful character trait. At the same time, it’s one that can, when applied in certain ways, lead to really unsubtle plot points. In a lot of fiction, cowardice is used as shorthand for lack of moral fibre. Calling someone a coward is tantamount to calling her a terrible person with no conscience who will die alone, probably by falling off something tall.* Why is John McClane of Die Hard so awesome? Because he’s never afraid of anything. Neither is Hans Gruber, which makes him the perfect antagonist. Both men are fearless, so their struggle must necessarily be to the death. Harry Ellis is the one who tries to take the cowardly way out (albeit in a reckless manner that probably has a lot to do with the cocaine). Ellis is not the only Die Hard character who is killed—and many who die, such as Mr. Takagi, are plenty brave—but with the exception of the villains, he’s the only one who dies and is meant to be utterly despised. His cowardice is conflated with his treachery to give us someone who is, in a way, worse than the hostage-taking, murdering terrorists.

The cowardice/treachery conflation is not uncommon. Give me a coward, and I’ll show you someone who will join the bad guys, becoming automatically worse than they are. An episode of Community, “A Fistful of Paintballs,” plays with this concept by having Ben Chang betray everybody during a game of Paintball Assassin. Chang’s constant switching of sides arises from his cowardice; he simply joins whoever seems to have the upper hand at the time. The episode is parodic, as many Community episodes are, and it thus exaggerates the trope to the point where it becomes obvious what’s going on: Chang’s true problem is not that he’s a traitor but that his constant fear of everything leads him to make decisions that take absolutely nothing but the fear into account. These motivations, less exaggerated but just as present, underlie many portrayals of fictional cowardly traitors. Their treachery is unforgivable, but it arises directly from fear.

Many have observed that bravery doesn’t exist without fear; people who aren’t ever afraid can’t be brave because they haven’t had a chance to overcome the fear. We therefore often make a distinction between “fear” and “cowardice.” The first can be overcome and thus doesn’t control the character; the second is in the driver’s seat and is therefore despicable. The word “cowardice” itself makes this fine line seem broader. You can be “afraid” and not a “coward;” it depends on how you react to the fear. Yet the broadening of this line sometimes, ironically, erases the distinction between “fear” and “cowardice” entirely. “Don’t be afraid,” Character X tells Character Y, as if it’s a choice. And so: “You’re not afraid, are you?” “There’s nothing to be afraid of!” “Well, if you’re scared…” “Chicken!” Over and over again, fictional characters mock fear. Being afraid itself is shameful. Being afraid is cowardice.

I wish we had more cowardly protagonists: not just fearful ones, but genuine cowards, people whose response to conflict or danger was to cave, not to fight back. When we paint cowards as entirely morally corrupt, we devalue fear. In reality, most of us are cowards. We’ll sometimes take the hard, brave path, but much more often, we’ll take the easy, fearful one. The consequences can be dire, or they can be negligible. Cowardice is not exactly good, but it’s normal and understandable. When we erase it from our stories as a common human trait, positioning it as uncommon and only accessible to pieces of human garbage who don’t deserve our sympathy, we ignore the bits of ourselves that succumb to the impulse to take the easy way out. We know we’re not bad people, so our cowardice must not really be cowardice. We’re acting out of justifiable fear. Wouldn’t anyone keep quiet while the scary fascist ranted about immigrants? Aren’t we, as good people, justified in hanging sensibly back from the fight? We can accept ourselves as fearful but not as cowards, and in the process, we absolve ourselves of responsibility.

So bring on the cowardly protagonists. Their cowardice doesn’t make them bad people. It makes them people. If we’re in denial about that, perhaps we should check our own cowardice.

*Okay, so not everybody who falls off something tall is a coward.