Revisiting a Viral Sensation 30 Years Later

If you were a bookish kid — and I’m willing to bet you were since you’re reading this newsletter — you probably have a memory of some very grown-up book that made its way into your awareness. Maybe you picked up your aunt’s Jackie Collins novel and didn’t even realize how much of it was flying right over your head. Maybe you tried your hand at Stephen King at far too tender an age (who among us doesn’t have this story?) and slept with the lights on for a week or five. Or maybe, like me, you came home from school one day in May of 1993 and saw your mom watching an Oprah episode about The Bridges of Madison County a full three years before Oprah would start her famous book club.

Before I went a-googling for it, I couldn’t recall exactly what happened in that Oprah episode — which is a truly wild 44 minutes of television — but I can’t forget what happened after: the slim, peach-colored hardback with an illustration of one of the titular covered bridges appeared on our coffee table.

My mom was reading it. My friends’ moms were reading it. All of the women at the neighborhood pool that summer were reading it. I feel like I remember seeing a copy on my teacher’s desk at some point, but who knows if that’s real. What I’m saying is: the book was everywhere. I didn’t know it at the time, but I was experiencing my first viral book moment. And I wanted in! I sneak-read my mom’s copy, felt Very Mature for a couple days, and have spent the ensuing 30 years sporadically remembering that Bridges was a big deal for a little while.

But HOO BOY, I had no idea how big of a deal it had been until I got curious about popular books of years past and found it high atop the list of the best-selling adult novels of 1993. At first blush, I assumed this had to be due to what we now know as The Oprah Effect. As I realized when I went back to reread the book and see if it might fit into more recent viral trends, it’s not that straightforward.

Like its contemporary successors, Bridges uses writing that is okay at best to present an idealized version of love, sex, and romance that reality can’t possibly compete with.

Robert James Waller’s debut novel, The Bridges of Madison County, was first published in April 1992. Its unnamed narrator tells us that he has written the story at the request of main character Francesca’s children. After her death, they found journals in which she documented the extra-marital affair that defined her life, and they believe the story is too compelling, too inspirational, too important to remain a secret.

Here’s the tl;dr version: Francesca grew up in Naples, Italy, and in her early 20s, fell passionately in love with a man her family didn’t approve of. After breaking it off, she met an American soldier named Richard Johnson (yep, Dick Johnson, I see it too), who was a safe, good-enough option. That’s right, friends. Our girl Francesca settled. She and Richard moved back to his native Iowa, where they have lived on a small farm in a rural community for the last 20 years, when the story begins.

It’s the mid-1960s, and Francesca is 45. Richard and their two teenage children are out of town for the week at a 4-H conference-type event when Francesca is sitting on the porch one afternoon when a handsome stranger driving a beat-up pickup truck comes down the drive. His name is Robert Kincaid. He’s a photographer who has been commissioned by National Geographic to capture images of the seven famous covered bridges of Madison County, Iowa. He has found six of them, but he can’t seem to locate the seventh. Can she point him in the right direction? She can do that, and then some.

Overcome by something she can’t identify, Francesca offers to show Robert the way rather than simply giving him directions to the bridge a mere two miles down the road. She hops in his truck, but not before noticing how “hard” his body is and thinking that he moves like a leopard or cheetah and gives off a “shamanlike” vibe. They make their way to the bridge, where she acts as his assistant while he “makes pictures” until the light goes down. She invites him back to the farm for a tension-filled dinner, and then he heads back to his motel; no vows will be broken tonight.

But Francesca, whose husband once told her that a certain pair of earrings “made her look like a hussy” and who, as we find out later, stopped having orgasms years ago, has other ideas. She nails a note for Robert Kincaid (whom Waller almost always describes using his full name) to the bridge he’ll be shooting at sunrise. When he comes for dinner that night — Francesca makes a stew, the most seductive of mid-summer meals — he stays for more than dessert.

Finally, 108 pages into the 183-page paperback, they go to Bonetown, where they’ll stay for the rest of the week. Or, as Waller puts it, “Robert Kincaid gave up photography for the next few days.”

And that’s basically it! They profess their love for each other, and Robert Kincaid invites Francesca to join him on the road. She declines out of a sense of responsibility to her family, and the two never speak again except for one letter and a few photographs Kincaid sends her in the mail before the National Geographic story runs. She spends the next two decades privately pining for him but claims she never regretted the choice to stay with Richard and their small-town life.

By the time Oprah got wind of it (a recommendation from longtime bestie Gayle), Bridges had been on the Best Sellers list for about nine months with more than 2 million copies sold. The book was already a commercial success, if not a critically acclaimed one; in a short review for The New York Times, Elis Lozoto functionally panned it, calling it “a bodice-heaving, swept-away-by-love romance, a soft-focus fantasy.” A few months later, a Times reporter investigating the phenomenon got the vice president and editor-in-chief of Book-of-the-Month Club to go on the record with the scorching take that Bridges had “successfully tapped into the rich market of middle-aged, world-weary people.” Eventually, the book was so popular that it became fodder for parody, snobbery, and everything in between, as documented in this gloriously titled piece, “The Grinches of Madison County.”

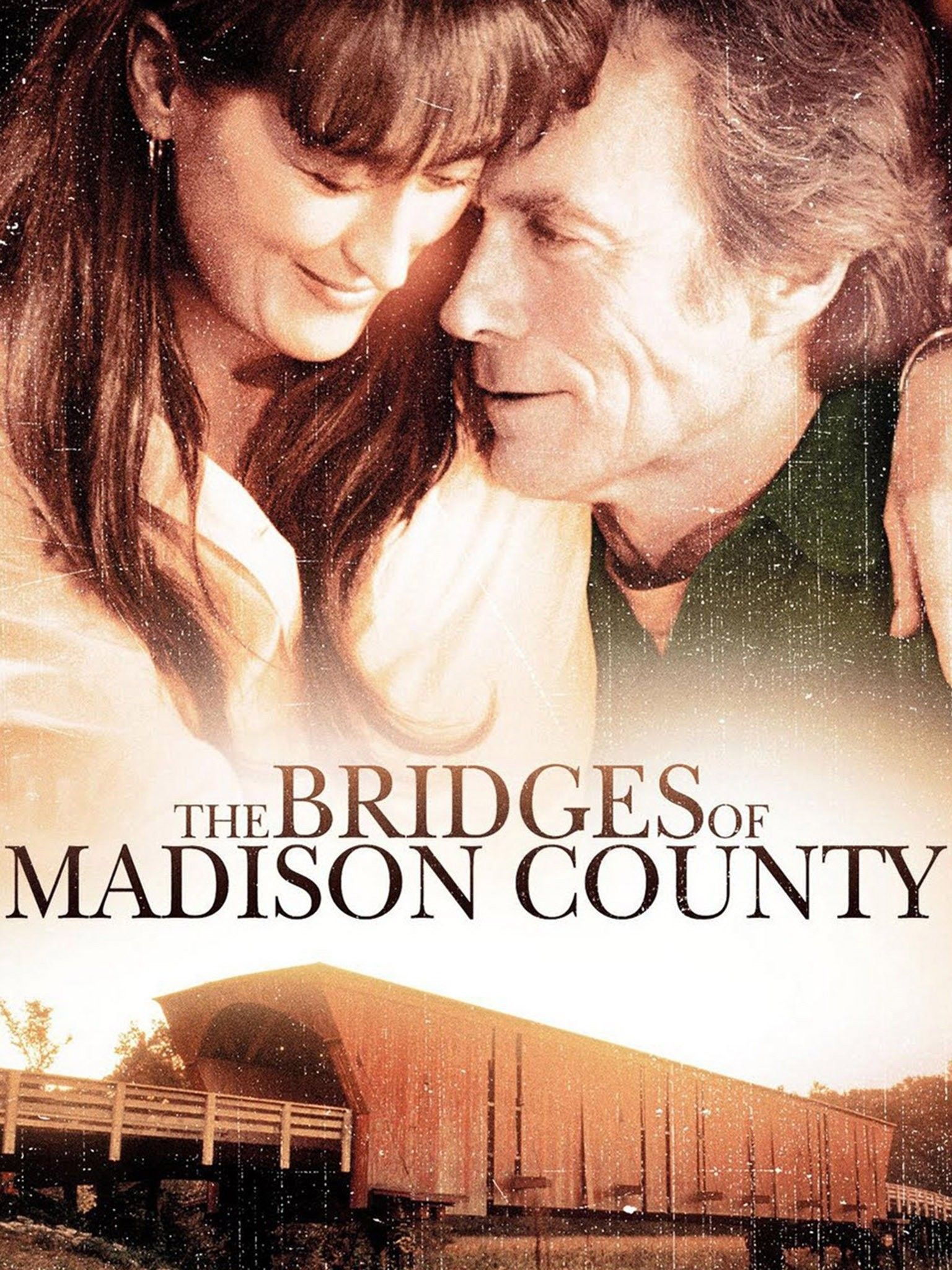

The Bridges of Madison County would spend more than half of 1993 in the #1 slot of the best-seller list. It continued to appear on the list throughout the following year, ending up as the ninth-most best-selling adult novel of 1994, according to Publishers Weekly. 1995 brought a film adaptation starring Meryl Streep and Clint Eastwood (in a just world, it would’ve been Harrison Ford), and though the book didn’t crack PW’s list of top-selling novels that year, it must have continued to sell because as of this writing, more than 60 million copies have been sold.

Now, 60 million books is a BFD no matter how you slice it, but let’s put it in context alongside more recent viral hits. Sixty million is about 40% of the total sales the Fifty Shades trilogy hit by 2017 before its star began to fade, and it’s…wait for it…more than THREE TIMES Colleen Hoover’s estimated total sales across more than 24 titles as of last year. Robert James Waller did that with no existing literary reputation and one single book, and, critically, without the benefit of social media. The Bridges of Madison County struck a hell of a nerve.

Like its contemporary successors, Bridges uses writing that is okay at best to present an idealized version of love, sex, and romance that reality can’t possibly compete with. It offers an escape and an invitation to consider “what if.” What if I’d married someone else, or not gotten married at all? What if I asked for what I want? What if I required a partner to treat me differently/better/etc.? That’s potent, empowering stuff. And it’s important stuff. But it’s far from unique among romance novels (though Bridges lacks a happily-ever-after ending and doesn’t technically qualify as romance), so…why this book?

It’s tempting—and it would be easy—to dismiss Bridges’ popularity as one more piece of evidence that mediocrity is a prerequisite for mainstream success. In one of his page-long mansplanations of cultural issues, Kincaid explains to Francesca that with art, “You’re always dealing with markets, and markets—mass markets—are designed to suit average tastes.” That’s a hell of an unintentional self-own. But while The Bridges of Madison County isn’t high art, it is better-written than Fifty Shades and It Ends With Us. That is, until you get to the sex scenes, which are somehow both minimally descriptive and also deeply ridiculous. To whit:

…she would begin to turn in her mind, breathing heavier, letting him take her where he lived, and he lived in strange, haunted places, far back along the stems of Darwin’s logic.

I mean, what?

But also, what do I know? It clearly resonated. Perhaps Waller’s less-than-detailed description of what, exactly, Francesca and Robert Kincaid were up to while he made love to her like she wanted him to (and held her tight, baby, all through the night) allowed readers to project their own erotic fantasies into the scene. Maybe reading about Kincaid’s incredible stamina—Francesca describes him as a “half-man, half-something-else creature”—in contrast to her husband’s short-lived, less-than-stellar style in the sack gave them permission to acknowledge that they too wanted more from their partners. Maybe the idea of tapping into “good feelings, old feelings, poetry and music feelings” is universally compelling, or maybe the BOTM exec’s more cynical reading was right. Or it could be that this book found the readership it did because, unique among its viral peers, it told a story about “middle-aged, world-weary people” (remember, middle-aged women are the publishing industry’s biggest consumers) and offered the hope of even a temporary reprieve. Which begs the question: could a four-day roll in the hay really be enough to make staying in a disappointing marriage tolerable for 20 more years? Oxytocin is a powerful drug, but come on.

Another powerful drug? A man who both exemplifies and defies stereotypical masculinity. Robert Kincaid is the ultimate Cool Guy. He’s “one of the last cowboys,” longing for simpler, freer times (he’s going to love the ’70s!). He is simultaneously physically powerful and emotionally sensitive, a sexual Energizer bunny who can go all night and whisper Rilke in your ear while he does it. He’s not interested in women who, however attractive, are too young to have “the ability to move and be moved by subtleties of the mind and spirit.” And he is a 1960s feminist or something like it, aware enough to make comments like “the curse of modern times is the preponderance of male hormones in places where they can do longterm damage.” Add in the fact that this book, unlike most popular romances, is authored by a man and theoretically reveals a man’s understanding of what women want, and you get a story that illustrates the ways in which the narrowly defined gender roles of patriarchal heteronormativity are impossible for everyone.

The more I’ve thought about what might explain the popularity of The Bridges of Madison County, the more I’ve come to accept that it’s probably the same combination of luck, timing, and zeitgeist magic that explains most phenomena of this size. The secret is that there is no secret; a hit like this can’t be planned or manufactured, and it certainly can’t be replicated. But if I had to put money on a theory, it would be this: The Bridges of Madison County made readers, specifically straight women, feel seen. It validated the pragmatic decision to opt for security over passion and the accompanying sense of loss, the deep loneliness of a virtually sexless marriage and the complicated choice to seek a momentary respite from reality. Waller didn’t judge his characters for their transgressions but instead tacitly endorsed the idea that what people don’t know can’t hurt them. Not only that, he advanced the fantasy that even when they do know, as when Francesca’s children learn of the affair, they’ll understand. Whether any of this is right is beside the point. It’s effective.

Like any piece of art, this book is a product and reflection of its time, and if the Oprah episode is any indication, there were plenty women in 1993 still stuck in unfulfilling marriages like Francesca’s. What does it mean that in the 30 years since, we’ve moved on to viral romances about exploring kink, leaving abusive relationships, and breaking cycles of generational trauma? I’m not sure it means anything, really, but I hope that when future readers revisit these more recent hits, they’ll have the same experience I had returning to The Bridges of Madison County. The feeling of “this hasn’t aged well” isn’t a bad thing; it’s exactly what we should hope for when we go back to stories that defined previous generations. I don’t know if people really thought The Bridges of Madison County was good in 1993, and it doesn’t really matter that I don’t think it’s good now. It met a need for an astronomical number of readers, and rather than lament that the newer hits aren’t any better, I’ll take it as a good sign that they are at least asking a different set of questions.

Leave a comment

Join All Access to add comments.