Level Up Your Reading: Become a Literary Magazine Volunteer Reader

For avid readers, sometimes books can lose their appeal. You might get burned out or are unable to find the joy in keeping up with all the latest book releases. You could take a break in reading altogether, but there are other opportunities to level up your reading skills while putting your eye for detail to good use. One of those opportunities to become a literary magazine reader.

I had the great privilege of reading for two literary magazines in the past — The Missouri Review and The Masters Review — and both experiences proved invaluable to me as a reader and writer. It opened up my eyes to the blood, sweat, and tears that editors and readers put into these small but mighty publications. From a writer’s perspective, it also created an added respect for editors.

Becoming a literary magazine reader is so important to literary magazines. Readers are the first eyes on submissions. They communicate with editors about their favorite pieces, including having (sometimes heated) discussions on what should make it through to final consideration.

Additionally, editors of literary magazines are often presented with hundreds (even thousands) of submissions while only having the budget for a select few. Reading for literary magazines, it became clear to me that receiving rejections for my work was/is not a personal attack on me or my work. It’s part of the process, part of the grind, and is often subjective.

The Importance of Literary Magazine Readers

To get a fully rounded view of the importance of readers for literary magazines, I interviewed editors of two literary magazines. I chose two recently created online literary magazines whose readers have been essential to their process of wading through submissions and finding work that speaks to the publication’s mission.

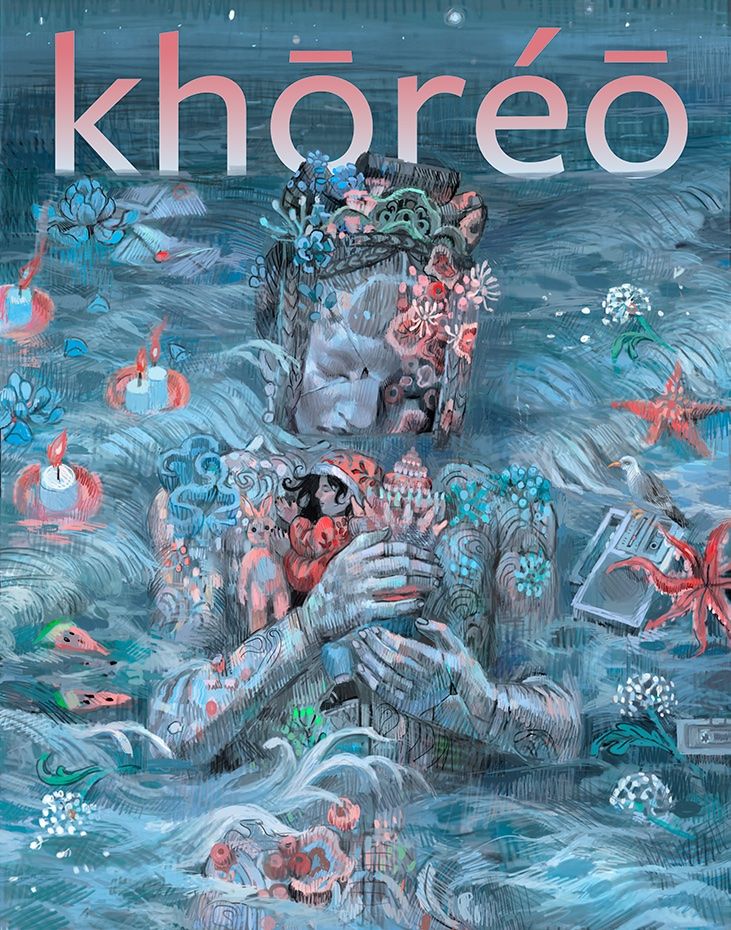

Aleksandra (Ola) Hill is the founder and Editor in Chief of khōréō, a quarterly magazine of speculative fiction and migration. It’s a magazine “dedicated to diversity and elevating the voices of immigrant and diaspora authors.” I’ve mentioned this magazine before in my list of must-read online literary magazines, and I deeply admire the breadth and quality of work khōréō is producing.

First readers are absolutely critical to khōréō, Hill said. Because of them, the magazine is able to give each submission the consideration it deserves.

“We typically get around 200 submissions in each submission month, which would be a lot for one or two people to wade through,” she said. “Because we have a large team, we’re able to divide all of our submissions among our readers and ask them to read each assigned story in full (unless it’s clear that the piece is a racist screed or something equally unpalatable). That means that even stories that might take a little bit to get started get full consideration and we don’t miss out on a gem of a tale that might otherwise have been missed because it should have really begun on the second or third page. It lets us really make sure that authors get a fair shake.”

Tommy Dean is the Editor of Fractured Literary and the recently-created Uncharted. Part of the family of literary magazines that includes Fractured, The Masters Review, and CRAFT, Uncharted seeks to publish speculative fiction, namely science fiction, fantasy, horror, thriller, and crime stories. It is a great publication for finding stories that artfully straddle the fence between literary and genre.

Dean said Uncharted’s readers are vital as well:

Editors and associate editors couldn’t read through the volume we receive with the necessary attention and speed. Volunteer readers definitely help us shape and fulfill our mission to create an exciting and diverse publishing and reading experience for anyone who supports our magazine!

What Editors Look For When Choosing Readers

If you’re interested in becoming a literary magazine reader, keep in mind the responsibilities entailed. Readers are often asked to read a certain amount of submissions on a weekly or monthly basis, marking which ones that strike their eye. You don’t need past experience at literary magazines to get involved, but your passion for the genre should be apparent.

At Uncharted, Dean said they are looking for readers of varied experience and backgrounds.

“We have a range from 18 to 70 years old as well as readers representing different underrepresented groups and cultures,” Dean said. “The experience levels of our readers vary as well as we like to provide people new to reading for lit mags an opportunity to gain this skill and experience while anchoring our teams with very experienced readers, editors, and writers who love genre short stories!”

Similarly, at khōréō, Hill said they look for readers that reflect the magazine’s aim to publish immigrant and diaspora writers.

“Wee do try to make sure that most of our first readers are either immigrants or members of a diaspora themselves,” Hill said. “We also ask each of our First Readers to share several stories that they think would be great fits for khōréō, since that gives a sense of what they value as readers and how well they understand what we’re trying to do. Someone who sends us only Hemingway is…not going to be a great fit for us and we clearly aren’t a great fit for them.”

Hill also said that kindness is an important factor when handling submitters’ work:

khōréō has no interest in gatekeeping or snobbery; we don’t want readers who take pleasure in finding the tiniest reason to reject a piece. We want readers who will pick up a story and read it and ask not just if the story is working, but try to understand what the author’s intent was. We want to publish great stories, but we want to publish them to bring out the author’s vision as clearly and beautifully as possible — not according to what we think the story should be. And achieving that goal starts with our first readers.

How to Become a Literary Magazine Reader

If the above information sounds interesting to you, I recommend the following steps:

- Depending on your preferred genre, search for literary magazines that cater to your interests. You can find a lot on the Poets & Writers database as well as The Submission Grinder.

- The most important thing to do — before you even consider submitting an application — is to READ WORK FROM THAT MAGAZINE. You might think it silly that I have to spell it out in caps, but it’s absolutely necessary (recall Hill’s example of someone trying to send khōréō a Hemingway story). Get a feel for that publication’s style and see if it’s something that connects with you.

- NOTE: If a call for readers for a new magazine opens up, obviously you can’t read past issues that don’t exist. In this case, read the application guidelines closely, and keep in mind the type of work that entertains and inspires you.

- Once you find magazines you’d be excited to read for, sign up for their newsletters, follow them on social media, and be on the lookout when a call for readers is posted.

- Follow the application guidelines and submit by the deadline!

Myna Chang, reader for Uncharted suggests keeping the following in mind when applying to become a reader:

Do you genuinely enjoy and admire the stories they feature? Also, be sure the publication’s philosophy and goals mesh with yours. Finally, don’t be discouraged if your application is not accepted on your first try.

Expand Your Reading Horizons

In addition to be an important part of the community of literary magazines and discovering great new writers, being a reader is a great new avenue for reading. It is where the act of discovery of something new and ground-breaking is exciting, and that excitement is contagious.

“First reading is awe-inspiring because you start to realize just how much you are only scratching the surface of what exists in peoples’ creative minds by reading published work,” Hill said of reading for khōréō. “Like I said before, we get about 200 submissions a quarter; we can only afford to publish five of those. Five. There are so many stories that we’ve had to reject that I still think about all the time, that I hope find a home because they were fantastic stories, they just weren’t the right fit for us, or we just truly didn’t have the budget.”

And for writers, being a reader is a constant learning experience. Dean started his literary magazine journey reading for several journals. Reading for a literary magazine helped him recognize excellent work and analyze why some stories don’t make it past first readers and associate editors.

“[Being a reader] has the value of being in a weekly workshop, where you get the chance to see today’s exciting stories and also get a vision of the future,” Dean said. “It helps the reader to work on their own writing, applying craft and getting rid of conventional images, characters, or plots. It may also prepare readers to take on larger roles within our magazine or with other literary journals as they continue to hone their critical reading eye, and their ability to communicate with other readers or editors what they believe is or isn’t working in a story.”

As a literary magazine reader, Chang said she’s learned how important it is for stories to be distinct.

“Some of the submissions in the reading queue are so well done, it can be intimidating,” Chang said. “This has pushed me to analyze my own writing from a more critical, more creative, standpoint.”

Finding Diamonds in the Rough

Finally, and perhaps even most inspiring of all, is discovering that truly amazing, mind-blowing story and being able to pass it on and see it forth to publication. Hill encapsulates that magic perfectly:

“You get to find those diamonds in the rough and you get to be part of the system that can unearth them,” she said. “You get to find a story you love, and yell THIS ONE! RIGHT HERE! and your advocacy can be part of the reason that that story gets published. And that, I think, is really, really cool, because even if this story doesn’t end up making the cut, you get to see the stories and authors you want to go to bat for and [the experience] lets you imagine what a better literary landscape would look like.”