Here Comes the Scribe: A Bookish Wedding Retold

Wearing tweed. Surrounded by vintage books. Pablo Neruda was there. As was Robert Burns. A Latin legend shared a dram with a soused Scot, while a 1960s typewriter rattled in the background to the tune of Irish poetry.

This bookish kaleidoscope is one of the abiding, if smudgy, memories of the day. There have been a few Book Rioters (Wallace Yovetich, Rebecca Jones Schinsky, Jennifer Paull) offering advice on how to weave an undying love of literature into the day when you declare the same to another person. Lee, my wife, and I decided to put their sage advice into practice.

This, dear friends, is how we had a bookish wedding.

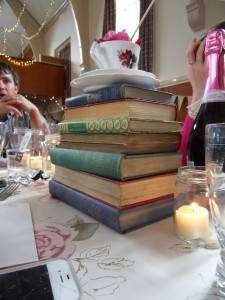

First of all, we needed the base material: books. Lots of books. The venue for our reception was Aberfeldy Town Hall, a community venue in a beautiful wee town close to the Scottish Highlands. It may have had the whiff of local bake sales and Girl Guide displays, but it was perfect for us. The plan was to fill it with bunting, candles, fairy lights, flowers plucked from local hedges, teacups, and vintage books with ornate bindings and handsome covers.

Luckily for us, a second-hand book shop in Edinburgh was going out of business. We pillaged it, purchasing 300 books, many for less than a pound. As a lover of bookshops this stuck in my craw. I felt like a vulture hovering over a wounded animal, awaiting its demise, before picking some first editions from its still-warm carcass.

Luckily for us, a second-hand book shop in Edinburgh was going out of business. We pillaged it, purchasing 300 books, many for less than a pound. As a lover of bookshops this stuck in my craw. I felt like a vulture hovering over a wounded animal, awaiting its demise, before picking some first editions from its still-warm carcass.

Thankfully, the owner assured us he had never made any money from the shop and was glad to see it shut. He now just restores antiquarian books and is very happy, thank you very much. Our conscience was assuaged.

Next up were the readings. As Rebecca has already noted, it’s hard to choose something in this department that feels fresh. Most readings at weddings are safe hand-me-downs from other nuptials, giving them a worn, dog-eared feeling.

So, we went Latin. I’ve always loved Pablo Neruda. Our friend Louise read Sonnet XVII (“I do not love you as if you were salt-rose or topaz…”). It’s long been one of my favourite expressions of closeness and intimacy. I always had it pegged for my wedding. So imagine my horror a few years ago when I had the misfortune of seeing the film Patch Adams. In it clown/doctor/man-child Robin Williams uses those very same lines to woo and mourn his wife. It’s like a Pixies song advertising Coca-Cola. A David Foster Wallace line being adopted as a Nike slogan.

For years I feared that if I used Sonnet XVII people would come up after, congratulate me on my marriage, and say how much they loved that Patch Adams poem. My inner snob shuddered. Then, frankly, I just got over myself. It’s a beautiful poem. Not even Robin Williams’ simian arms can ruin it.

Being Christians, alongside Neruda we had a medley of Biblical readings on love and trust. When John wrote “There is no fear in love, for perfect love drives out fear,” he achieved poetry.

Being Christians, alongside Neruda we had a medley of Biblical readings on love and trust. When John wrote “There is no fear in love, for perfect love drives out fear,” he achieved poetry.

And then there was Robert Burns. He was everywhere. We had a post-ceremony dram in The Kenmore Hotel. Perched on the banks of the River Tay it is famous for two things: dating from 1572, it is Scotland’s oldest inn; and Burns graffitied the wall in the bar with a poem. He was the Banksy of the Enlightenment.

He also wrote The Birks O’ Aberfeldy, a love song tempting his lass away with him to explore the beautiful, waterfall-strewn gully that rises from the town centre of Aberfeldy into the hills behind. Burns was also the Patch Adams of his time. I walked that same forested path early on the wedding morning, trying to channel the Bard and compose a few pithy, witty, and moving lines for my speech. And I think I succeeded; if you consider weepy, overlong, over-sentimental performances to be Burns-like.

Words were exchanged in other ways. A vintage typewriter took the place of a guest book. Several of the books went home with new owners. Telegrams were read out, some from certain good people at Book Riot. And garbled sentences were offered up to everyone, as we struggled and fumbled away towards articulating how grateful we were.

Words were exchanged in other ways. A vintage typewriter took the place of a guest book. Several of the books went home with new owners. Telegrams were read out, some from certain good people at Book Riot. And garbled sentences were offered up to everyone, as we struggled and fumbled away towards articulating how grateful we were.

In the end, as always, we reverted to our books. This was how another poet made a final cameo. When you want clarity and a neat turn of phrase, always go Irish. WB Yeats stepped up during the speeches and proclaimed a truth to all in a wee Aberfeldy hall on a midsummer’s evening: “Think where man’s glory most begins and ends, And say my glory was I had such friends.”