Why Hating Paper is Old-Fashioned

This is a guest post by Derek Attig. Derek is a graduate student in History at the University of Illinois where he is writing about bookmobiles in American culture. Particularly interested in the relationship between information technology and the reading life, Derek was a 2012 Google Policy Fellow at the American Library Association’s Office for Information Technology Policy. Oh, and he blogs at bookmobility.org. Check it out! Follow him on Twitter @bookmobility.

____________________________

These days, it’s not unusual to see debates over the effects of digital technology play out in battles over paper. Digital devotees shout their love for sleek, convenient, multitasking screens from the rooftops. Paper partisans strike back. Printed books, they insist, are more relaxed, more romantic, more shareable, and just plain sexier and more sensual. (I’ve staked my own rather ambiguous claim on the relationship between e-readers and paper books, too. It seems it’s de rigueur if you write or think about books and reading these days.)

But it turns out this debate is actually a few decades older than the Kindle. In fact, it was largely kicked off not by ereaders or tablets but by early efforts at computer networking and the “paperless offices” they promised. Recently, while researching a chapter on bookmobiles and digital technology, I came across a film—“Computer Networks: Heralds of Resource Sharing”—created in 1972 by the Advanced Research Projects Agency (the people who brought us ARPANET, a precursor to the Internet) and preserved by the lovely people over at the Internet Archive. Part sort-of-mind-numbing introduction to networking technology circa 1970 and part super-geek variety show, the film has all the big names: Bob Kahn and Lawrence Roberts both make appearances, for example. But the heart of the film is computer-age Zelig J.C.R. Licklider. (Seriously, start looking into just about any computing development in the second half of the twentieth century, and you’ll soon find Licklider’s not-very-smiling face.) And a surprising amount of Licklider’s time on screen is devoted to the problem—oh yes, problem—of paper. Good old Lick hates the stuff:

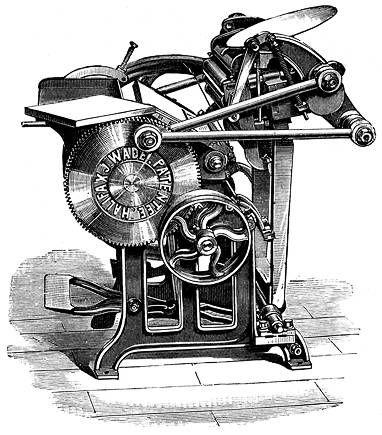

“It’s been hard to, well, share information for years. The printing press, of course, was the great step into sharing information, but the printing press didn’t essentially handle the problem of distributing it. … And we have been needing for a long time some better way to distribute information than to carry it about. The print on paper form is embarrassing, because in order to distribute information, you’ve got to move the paper around. … It’s just fundamental that if one wants to deal with information, you ought to deal with the information and not with the paper it’s written on.”

I love its audacity, but I’m also exasperated by Licklider’s melodrama. Embarrassing? Really?! Not to mention that computer networking relies on physical stuff—a series of tubes—to move information, just like printing presses and paper books do. But there’s no denying the force and influence of Licklider’s opinion. We’re living, and reading, in the world he made.

Indeed, fascinatingly, Licklider also essentially foresaw Google Books and stopped just short of predicting the Kindle:

“So that if everyone had a display console in his home and in his office, he could be reading from electronically-stored information instead of from a book, and the difference is he could have access to anything he wanted to read instead of just what was within reach. Well, it turns out to be surprisingly inexpensive, if you get wide-band transmission facilities, to send the stuff right when it has to be read instead of sending it to a local bookstore or local library in the hope that it might be read.”

So I recommend giving the video a watch. You might learn something about packet-switching or IMPs. And next time someone says something disparaging about paper books? You can say, with a bit of pity in your voice, “That’s just so, well, seventies.” That’ll teach ‘em.