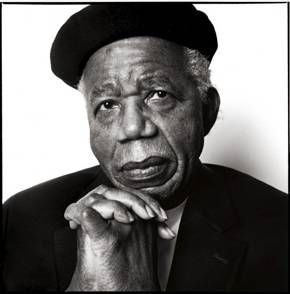

The Centre Cannot Hold: Chinua Achebe and Rewriting the World

Over the course of his 82 years Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe attracted many titles. To some he was the Father of African Literature. To others he was the Great Slayer of Colonial Fiction. To me, well, he simply changed my world.

My encounter with Achebe is rather generic. I have read only one of his books. That book is Things Fall Apart. I read it as part of a university course. Millions of folks are nodding at this familiar tale.

And yet, on Friday when I heard he had died, I stopped for a moment. His death tugged at a part of me usually unmoved. What week passes without the loss of a famed artist? And yet I mourned and celebrated this man. Why? Because he created the rarest of literary beasts: a book that actually flipped how I saw the world.

When I read Things Fall Apart I was 19. It was the first piece of art that got under my skin and made me realise that I wasn’t at the centre of the world. Achebe lit a fire under my unrealised prejudices. All my white European cultural certainties became hand-me-downs to be viewed with suspicion. A few years later my girlfriend at the time went to Africa on a mission trip with her church. I urged her to read Things Fall Apart. I felt it was as urgent and vital a book for her as The Bible.

For those unfamiliar with Things Fall Apart, let’s get all Cliff’s Notes for a second. First published in 1958, it tells the story of Okonkwo, a ‘big man’ within the Igbo people (a heritage shared with Achebe) in pre-colonial Nigeria. He is successful yet has a troublesome family life – his father was a wastrel and his son is a disappointment – and his status within his village constantly causes him anxiety.

Remove the blood sacrifices and consultation of oracles and Okonkowo could be a John Updike character.

And that’s the first part of Achebe’s genius. He takes a potentially alien situation – African village steeped in nuanced local custom and myths – and makes it universal. The whole world exists within Okonkwo’s community. It is an imperfect one full of celebration, tradition, justice, pettiness, and compassion.

And then comes Things Fall Apart‘s sucker punch. Achebe zooms out and reveals, well, me. And probably you too.

Lurking on the edges of Okonkowo’s society, like a lake about to break its banks, is the white man. Specifically white, European, Christian man. It is like the climax of the film Zulu, only with the roles reversed.

For the reader in the West it is sobering to realise that it is us, yes us, that are the rough beasts slouching towards Bethlehem. We are the harbingers of doom. Our sickening hour has come round at last. Okonkwo doesn’t stand a chance.

Things Fall Apart is the ultimate example of walking in someone else’s shoes. It is literature operating at its highest level – recasting your world from a completely different perspective. Achebe said it himself. A writer’s job is to “create a different order of reality from that which is given to him.”

The “order of reality” that he was consciously rewriting was one laid down by the likes of Joseph Conrad in Heart of Darkness. Until Achebe, Africa in literature was a savage place, dangerous, liable to tip into anarchy at any time. It was a continent waiting for the white man to either bring order to or to provide a backdrop for madness to devour him. Africa was reduced to mad mutterings in the dark.

But in the face of Achebe’s revolutionary idea of an African writing about Africa, it was Conrad and his ilk who didn’t stand a chance.

So farewell then Chinua. Thanks for changing the world.