13 Pioneering Black American Librarians You Oughta Know

In the United States, there was no formal training for individuals working in libraries prior to 1850. Training was completed through apprenticeship where individuals learned under the guidance of an experienced mentor or through trial and error. For obvious reasons (*cough* slavery *cough*), it is probably safe to assume most of those individuals were white (and male).

Professional librarianship began in 1876 with the formation of the American Library Association, the founding of American Library Journal, and the publication of Melvil Dewey’s decimal-based system of classification. Concurrently, there was an increase of libraries being built across the United States partly due to the philanthropy of Andrew Carnegie.

Many of the libraries Carnegie built were academic libraries at Historically Black Colleges and Universities like Tuskegee Institute, Atlanta University, Fisk University, and Howard University. At these universities, the majority of black librarians were trained, made significant contributions to library science, and left a legacy for future librarians of all races.

Here are 13 pioneering Black American librarians you’ve probably never heard of, but should definitely know. However, this is not an exhaustive list and represents only a fraction of the black librarians who have made significant contributions to librarianship. Hopefully, learning more about these library pioneers will inspire further exploration of other trailblazing Black American librarians.

Charlemae Hill Rollins, Advocate for Diverse Children’s Literature

Charlemae Rollins spent 31 years as the head librarian at the Chicago Public Library where she instituted substantial reforms in children’s literature. During the early 20th century, most of the books geared toward children included negative stereotypes of black people. Rollins’s first publication We Build Together: A Reader’s Guide to Negro Life and Literature for Elementary and High School Use provided criteria for selecting children’s literature with more honest portrayals of black people and their lives. Following the publication of We Build Together, Rollins became a prominent leader in children’s literature.

“Children as they are growing up need special interpretations of the lives of other peoples, [and] must be helped to an understanding and tolerance. They cannot develop these qualities through contacts with others, if those closest to them are prejudice and unsympathetic with other races and groups. Tolerance and understanding can be gained through reading the right books.” —Charlemae Rollins

Along with making inroads in children’s literature, Rollins paved the way for Black Americans in her profession. Prior to Rollins becoming the first black librarian to serve as president of the Children’s Services Division of the American Library Association in 1957, the ALA held segregated meetings. Rollins also became the first Black American to receive honorary lifetime membership in the ALA.

Clara Stanton Jones, The First Black President of the American Library Association

After receiving a degree in Library Science from the University of Michigan, Jones accepted the position as director of the Detroit Public Library and became the first black director of a major city public library. Soon after becoming director of the Detroit Public Library, Jones was elected the first black president of the American Library Association. During her tenure as director and president, Jones worked to desegregate libraries and their services as well as improve library culture by encouraging the ALA to pass the “Resolution on Racism and Sexism Awareness.”

Dorothy B. Porter, Dewey Decimal Decolonizer

In 1932, Dorothy Porter earned an M.S. in library science from Columbia University and became their library school’s first black graduate. However, she may be best known as the librarian who changed how works by black writers are classified. Overall, Porter’s classification method challenged the inherent racism and colonial gatekeeping of knowledge within the Dewey Decimal System.

Most of Porter’s library career was spent building the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University into a world-class research collection on Black/Africana history and culture. A substantial portion of the library’s collection was gifted by Howard alumnus, Reverend Jesse E. Moorland and NAACP’s legal committee chairman Arthur B. Spingarn. These acquisitions were the backbone of the university’s library. Porter was concerned with assigning proper value and classification to the collection. However, at the time of acquisition, no other library in the country had expertise in properly classifying works by black authors.

Every library Porter consulted for classification guidance relied solely on the Dewey Decimal Classification. In that system, black scholarly work was classified using either the number 326 that meant slavery or the number 325 for colonization. For Porter, it became necessary to develop a satisfactory classification workaround for this collection that did not reimpose stereotypes of black culture that prevailed within the Dewey Decimal System. Porter classified works within the collection by genre and author in order to highlight the role of black people in all subject areas like art, education, history, medicine, music, and even literature. This approach helped to combat racist stereotypes and false narratives while celebrating black self-representation.

During her over 40-year library career, Dorothy Porter devoted herself to developing a modern research library at Howard University. Not only did she build a world-renowned library for special collections of the global black experience, she also became a pioneer in the field of library science through her challenge of the racial bias within the Dewey Decimal System.

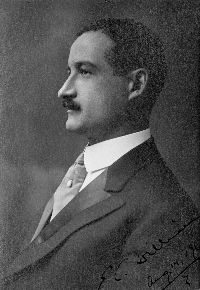

Edward C. Williams, America’s First Black Librarian

In 1898, Williams took a sabbatical from Western Reserve University to pursue a master’s degree in librarianship at the New York State Library. After completing his degree, Williams returned to Western Reserve University to serve as library director. During his tenure, Williams doubled the size and increased the quality of the university’s library collection and helped establish the School of Library of Science.

Following his career at WRU, Williams left Cleveland for Washington, D.C., to become a high school principal and then head librarian at Howard University. Similar to this time at WRU, during his career at Howard University, Williams worked to improve the quality of library resources and advocated for more professional personnel. In 1929, Williams took a sabbatical from Howard University to pursue a doctoral degree in library science at Columbia University. However, he died unexpectedly soon after beginning his studies.

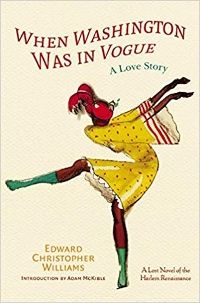

In 1999, American Libraries named Williams as one of the “100 Most Important Leaders We Had in the 20th Century.” His novel The Letters of Davy Carr was rediscovered in 2004 and published as When Washington Was in Vogue. The discovery helped to establish Williams’s place in the canon of Harlem Renaissance literature.

Eliza Atkins Gleason, Library Science Trailblazer

In 1940, Eliza Atkins Gleason became the first Black American to earn a doctorate in library science at the University of Chicago. Her dissertation entitled, The Government and Administration of Public Library Service to Negroes in the South, was the first complete history of library access in the South with a focus on African American libraries.

Her research documented the existence of many racially segregated public libraries and noted that Southern cities and towns did not have the financial means to create and maintain two separate systems. She suggested the better (and more logical) alternative of funding a single library that served all community members equally. The University of Chicago Press published Gleason’s dissertation as a book the following year that was highly acclaimed and positively reviewed.

From Chicago, Gleason went to Atlanta University to serve as Dean of their newly established School of Library Science. The school’s program was designed to train black librarians to serve in the public libraries from Gleason’s research as well as in the academic libraries of black colleges and universities. By 1986, Atlanta University’s School of Library Science had trained 90% of the country’s black librarians.

From 1942 to 1946, Gleason was the first Black American to serve on the Council of the American Library Association, and her legacy with the ALA continues to present day. In recognition of Dr. Gleason’s profound contributions to library history and library science education, the ALA awards the triennial Eliza Atkins Gleason Book Award for the best English-language book in the field of library history.

Sadie Peterson Delaney, Godmother of Bibliotherapy

Sadie Peterson Delaney received her library training at the New York Public Library School, which she attended from 1920 to 1921. Following her training, Delaney continued working at the 135th Street Branch of the New York Public Library. During this time, Delaney increased the number of programs available for children with a focus toward juvenile delinquents, blind children, and foreign-born children. She also worked with parents to understand the value of the library for their children. Delaney was also integral in developing an African American collection at the New York Public Library and established its first African American art exhibit.

Delaney’s extensive work using bibliotherapy, the practice of reading certain books for their healing purposes, came during her career as the head librarian at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Tuskegee, Alabama. By giving patients more individualized attention to learn their interests, Delaney used that knowledge and consulted with the medical staff to pair patients with books that would engage them. To complement her work with bibliotherapy, Delaney developed special programs like book talks, story hour, the Disabled Veterans’ Literary Society, and even a book cart to bring books to bedridden patients. She also taught blind patients how to read Braille and created a special department for the blind.

Sadie Delaney’s bibliotherapy became so popular that her library was used as a model for other Veterans Administration hospitals. Library science students and university librarians from around the United States were sent to observe and learn from Delaney. Even librarians from Europe and Africa came to learn bibliotherapy, and Delaney was often invited to give speeches on the subject.

Although Delaney’s contributions in bibliotherapy have a lasting legacy, her name is often left out of the discussion. While she is highly cited in articles by librarians and medical professionals, she is not well known outside of those fields. In 2015, Words Heal, the nonprofit organization that promotes bibliotherapy as a complement to traditional mental health treatments and therapies, added “The Sadie Peterson Delaney Literary Collaborative” to their name. During the same year, The New Yorker published Can Reading Make You Happier? The article references bibliotherapy, but there is no mention of Delaney.

Other Pioneering Black American Librarians

Annette Lewis Phinazee

Dr. Phinazee was both the first woman and the first Black American woman to earn a doctorate in Library Science from Columbia University. She earned the degree in 1961 with her dissertation entitled The Library of Congress Classification in the United State: A Survey of Opinions and Practices with Attention to the Problems of Structure and Application. Her research examined how the Library of Congress classification system was used by both librarians and library patrons. It was one of the first instances where patron use of the system was examined and has been described as a seminal work in library science.

Carla Diane Hayden

Effie Lee Morris

Effie Morris was a children’s librarian and activist who is best known as pioneering library services for minorities and the visually-impaired. She was also the first woman and first black person to serve as president of the Public Library Association. Morris focused on literacy for black and low-income children at the Cleveland Public Library and was the first children’s specialist for visually-impaired patrons at the New York Public Library. In fact, Morris was the only librarian in the country working with blind children during this time. Morris continued her streak of firsts at the San Francisco Public Library where she was the first black person to hold an administrative position as the library’s first Children Services Coordinator.

Mollie Huston Lee

Mollie Lee was the first black librarian in Raleigh, North Carolina. She also founded the Richard B. Harrison Public Library in 1935, the first library in Raleigh to serve Black Americans. During her 42-year library career, Lee increased public library service to Raleigh’s black population while striving for equal library services for the entire community. She also trained future librarians from Atlanta University, North Carolina Central University, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Virginia Lacy Jones

Virginia Proctor Powell Florence

Virginia Florence became the first black woman in the United States to earn a degree in library science from the Pittsburgh Carnegie Library School. She was also the second Black American to formally train in librarianship following Edward C. Williams. Florence also made history by being the first black person to pass the New York state high school librarian exam. During her library career, Florence worked as a public librarian at the New York Public Library and as a high school librarian in Brooklyn, New York; Washington, D.C.; and Richmond, Virginia.

Vivian G. Harsh

On February 26, 1924, Vivian Harsh became the first black librarian for the Chicago Public Library where she passionately collected works by Black Americans. The Harsh collection is currently located at the Woodson Regional Library and contains rare books, historical periodicals, and archival documents of the black experience (especially in Chicago) and is the largest black history and literature collection in the Midwest.