Our Reading Lives: Chasing Comics

The first time I saw Chasing Amy, I’d never picked up a comic book in my life. I was in eleventh grade and wallowing in the depths of unrequited adolescent love for one of my gay male friends. That, combined with a need to fulfill the unspoken requirement that all New Jersey youth must watch Kevin Smith’s oeuvre in its entirety, led me to rent the movie from my local Hollywood Video. I liked it well enough, right up until the point where self-identified lesbian Alyssa falls in love with Ben Affleck’s character, Holden. I rolled my eyes, bemoaned my inability to relate to Holden’s emotional arc any longer, and watched the rest of the film grudgingly. The fact that it was a movie about comic book creators didn’t even register with me as relevant. My interest in comics was still years away.

My understanding of the fluidities of human sexuality came more quickly, however, and by the next time I watched the movie, I was more sympathetic to the story’s complicated almost-love triangle between Alyssa, Holden, and Holden’s BFF/collaborator, Banky. By the third viewing, I’d decided to buy the DVD. The story – its humor, its emotional beats, its characters, Ben Affleck’s overwrought, ill-advised monologues – all appealed to me in a way that few other films had. In some strange way, Holden’s consummated relationship helped me to relinquish my own unrequited feelings. And every time I watched the film after that, I got more out of it. It became my go-to movie to watch if I was bored, or sad, or just wanted something on as background noise while I worked on something else. Before long, I’d memorized half the dialogue, and it had climbed undeniably into my top 5 list of favorite films.

A few years later, while home from college for the summer, I decided to take a pilgrimage of sorts to the Red Bank area, where Kevin Smith’s films were set and mostly filmed. It wasn’t exactly an epic journey – I lived about twenty minutes away – but I hadn’t spent much time there in the past. I made the requisite visit to the Quick Stop from Clerks, but most of my stops were at Chasing Amy locations: the diner where Alyssa buys a painting off the wall; the doorway that allegedly led to the staircase to Holden and Banky’s apartment; Jack’s Music Shoppe, where Holden has a revealing conversation with his friend Hooper. And across the street from Jack’s was Jay and Silent Bob’s Secret Stash – Kevin Smith’s own comic book shop.

It wasn’t the first time I’d been in a shop (that would have been 1994, when I was in elementary school and buying Pogs, unaware that the Spawn comics on the spinner rack by the Pogs counter were the store’s real bread and butter), but it was the first time I’d ventured inside as an adult. Whatever the store’s reputation now, as the subject of the Comic Book Men TV show, the staff was courteous and helpful that day, and while I was only there to look at the Kevin Smith memorabilia, not the new issues that lined the walls, it felt like a safe place I could return to someday.

When I finally started reading comics – due in large part, ironically enough, to the generous lending and recommendation habits of that same friend I’d once been in love with – some part of my brain started activating the knowledge I hadn’t even known I’d gained from all those viewings of Chasing Amy. When my friend lent me Pete Milligan’s X-Force/X-Statix, I recognized Mike Allred’s art as that which had been “Holden’s and Banky’s” in the film. And though I was still unschooled in the complicated dynamics of collaborative comic book production, I already knew what an inker was. (I later learned that many professional inkers hate the film, and the “You’re just a tracer!” joke it presents, then debunks. I can’t say I blame them. I wouldn’t want the most famous fictional member of my profession to be Banky Edwards, either.) A few more viewings and a few more months of comics reading later, I was picking up on the cameos from real comics pros — Jimmy Palmiotti, Joe Quesada, and Allred himself.

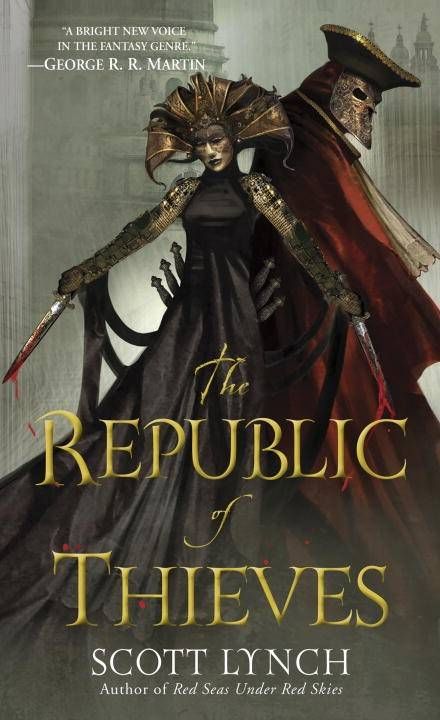

Soon after, another friend tried to sway me to DC by handing me Kevin Smith’s Green Arrow story, “Quiver.” I liked the book, and Smith’s characteristic humor, though it didn’t succeed in hooking me on the DCU. Still, seeing Kevin Smith’s work on an actual comic book, after I’d become so familiar with his depiction of comic book professionals, was eye-opening. And every time I watched the movie after that, I understood more and more of what the film was commenting on, including a lot of things that sadly haven’t changed much since its release in 1997: the race and gender makeup of mainstream comics publishing, poor behavior of fans and pros alike at conventions, and the financial and artistic tension felt by creators as they choose to devote their time to corporate comics or creator-owned.

I also started noticing the film’s flaws, things I might not have picked up on in high school, before my own social justice education. While the frank depiction of complicated sexuality is admirable, the film still falls down in several ways where race, gender, and queerness are concerned; I still adore it, but I cringe at some bits, and I couldn’t in good conscience argue with anyone’s criticisms. Meanwhile, my increasing knowledge of the comics industry and its interpersonal dynamics made me look askance at some of the characters’ behavior, making me less sympathetic to Banky’s rage or Holden’s creative pretentiousness. I still liked the characters, but I knew I wouldn’t want to deal with them in real life.

When I started working at Marvel, I brought in a small still from Chasing Amy that I’d cut out from an issue of Entertainment Weekly. It featured the three main characters on a couch, captured at the film’s climax, all of them emotionally wrung-out. I rolled up a piece of tape on the back of the image and stuck it to the corner of my computer monitor. Whenever I had a bad day at work, I’d look at the image and think, “Hey, it could be worse. These jerks could be my freelancers.” The next time I watched the film, I kept an eye out for Joe Quesada’s cameo, and pondered the oddity of seeing my boss in the background of a movie I’d first watched a decade earlier.

I’m no longer a comics professional, but now I’m something else: an academic, heading toward a PhD in media studies with a focus on comics. Chasing Amy, after everything, still stands squarely at the intersection of all of my interests. I’ve crossed that intersection as a non-fan, a fan, and a pro, and now I’m crossing it again as a scholar – and I’m sure I’ll discover something new, just like I always have before.

In fact, I think I’ll put the movie on right now. It’s been too long.