Nobuko Yoshiya: 1920s Revolutionary Lesbian Novelist

You might not know the name Nobuko Yoshiya. I didn’t, until very recently. She was a wildly successful author in Japan, so much so that her book’s royalties brought in enough money for her to own five houses, one of which is now a museum about her. Despite all her accomplishments, her books have rarely been translated into English.

Yoshiya was a revolutionary. Her writing made romantic feelings between women palatable to mainstream Japanese readers, and while her stories may not have radically challenged gendered expectations, her real life did. Clémence Leleu’s Pen Online bio explains that Yoshiya’s success made her financially independent, and she was more androgynous in her hair and clothing style than most women were at the time. She was openly in a lesbian relationship with Monma Chiyo throughout her writing career, yet she was never adopted as a modern queer icon.

It’s hard to understand why not. She didn’t succumb to a lavender marriage or stay mysteriously single; no, Yoshiya publicly acknowledged her relationship with Monma in interviews. The women lived together for 50 years, collaborating on their work and travelling together. In Japan, two women could not get married, and so in 1957, Yoshiya adopted Monma as her daughter. Adoption was the only legal way for them to share property and be in control of each other’s medical decisions. That’s chutzpah, if you ask me, finding a loophole in an unjust system.

Career and Legacy

Leleu’s biography paints a picture of Yoshiya as groundbreaking from a young age. The only daughter out of five kids, Yoshiya left her conservative family in Tochigi Prefecture and moved to Tokyo. She attended a few meetings of Seitō, Japan’s pioneering feminist magazine, and met other women writers. Her style changed as she chopped her hair into a short bob and gave up wearing skirts and kimonos. With this newly androgynous style, she submitted her writing to magazines like Shkjo sekai (Girls’ World).

In 1916, Flower Tales was published. It’s a collection of short stories set in boarding school that told stories of young women amid intense emotional relationships with teachers or other students. The relationships portrayed did not culminate in physically requited romances — maybe a chaste kiss here or there.

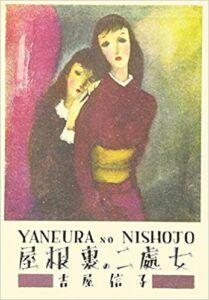

In 1919’s Two Virgins in the Attic, the love story is between Akiko and Tamaki, two dormmates who move in together. Sabrina Imbler writes in Atlas Obscura that the two young women “spy on each other in the bathroom and smell each other’s scent of ‘lily magnolia’ — all culminating in a kiss.” Akiko and Tamaki end up together, their happily ever after achieved. Imbler explains that “[m]any manga scholars consider Two Virgins in the Attic to be the first prototype of yuri manga, the modern extension of shōjo that is more explicitly focused on lesbian romantic and sexual relationships.” Imbler also quotes Hiromi Tsuchiya-Dollase, a professor of Japanese at Vassar College, who points out that while Japan had some representation of gay men in art and literature, there was nothing showing female homosexuality at the time. That made Two Virgins even more groundbreaking.

Unfortunately, at the time of Two Virgins’ publication, popular culture was becoming more puritanical again. To remain successful, her work needed to conform to the expectations of a broader audience of readers, and she did that by emphasizing the innocence of her characters while making the romances implied.

According to Leleu, Yoshiya’s work after Two Virgins cut back on showing explicit queerness and the rest of her oeuvre mainly dealt with unhappy homemakers in books like To the Ends of the Earth (1920), Women’s Friendship (1933), A Husband’s Chastity (1936), Demon Fire (1951), The People of the Ataka Family (1964), Tokugawa Women (1966), and Ladies of the Heiki (1971). In many of these, the put-upon housewife would grow close to a female friend, but implicit as their love might be, it never ended well. Unfortunately, some of Yoshiya’s stories would be easily packaged alongside examples of the Dead Lesbian/Bury Your Gays trope, but I like to think that she wouldn’t have ended the stories that way if she were still alive and writing.

Shōjo Manga

Looking over Yoshiya’s biography, I couldn’t help but note all of her impressive accomplishments. She wrote beloved novels from the 1910s to the 1970s, and many of her works have been adapted for mediums like film, television, radio, Takarazuka theatre, and manga. She’s even credited for influencing an entire form of manga — her stories, with their floral themes, boarding school location, and emphasis on emotion and romance were precursors to the modern shōjo manga genre. The term shōjo, meaning girl, became popular in the early 1900s, and so shōjo manga roughly translates to comic books for girls. It’s a huge cultural success in Japan, and Yoshiya is one of its founding writers. Deborah Shamoon, an expert in modern Japanese literature, film, and popular culture, wrote a book in 2012 about Yoshiya’s influence — Passionate Friendship: The Aesthetics of Girl’s Culture in Japan. In the text, Shamoon explored how shōjo tends to be hyper-feminine, even stereotypically so, with imagery of dreamy teenage girls surrounded by flowers, dolls, and other markers of whimsical femininity. Often, shōjo manga’s drawing style will emphasize childish aspects — think of Sailor Moon and her giant tears, for example.

Shamoon wrote, “Shōjo manga is not just a genre of comics aimed at a specific demographic; it is a part of girls’ culture (shōjo bunka), a discrete discourse on the social construction of girlhood.”

After all, the stories are often set in school dormitories, away from parents and men for the first time in their lives. This allows the girls unsupervised and uncontrolled time away from societal expectations. As Sarah Frederick argues in Bad Girls of Japan, Yoshiya’s girlish writing style was a way of showing resistance against the gender-based views of the time. Especially during the early part of the 20th century, women were often only viewed as successful after becoming wives and mothers. Yoshiya’s writing allowed teenage girls to recognize their stories mattered.

However, the genre can be jarring for Western feminists because instead of creating stories that subverted gendered expectations, Yoshiya’s writing embraced the symbols of clichéd girlish youth. It can be easy to dismiss Yoshiya’s works as schmoopy, unrealistic fiction about boringly pure girls. Critics called her writing “flowery” and self-absorbed; later, Yoshiya critiqued her early writings for their lack of character development.

Still, even if there were problematic aspects of her writing, she championed female relationships and upheld women and girls as the driving forces in stories. Also, she lived a successful, openly gay life with a woman she loved and didn’t allow homophobic laws to keep them from taking care of each other. That makes her damn iconic and well-deserving of being better known outside of Japan.