The Five Times I Read NIGHT, and the One Time I Couldn’t

This is a guest post from Callie Ryan Brimberry. Callie is a teacher, writer, and editor in Virginia. She spends her free time leaving books on park benches and in random coffee houses, hoping her margin notes read like love letters to those who’ve yet to fall in love with reading.

I read Night again in college and shed my own tears when my professor cried as he spoke of Mr. Wiesel’s experience, as well as that of his own grandfather, who had been murdered in Auschwitz. In that moment, teaching became a much more humane occupation to me. Whereas before I had seen most teachers as compliant in a process that did not advocate for the well-being of children, I now saw teaching as an opportunity to battle the injustices of the world.

When I moved to San Diego, I found a copy of Night in a bookstore in Hillcrest. It had a different cover than the one I owned and, of course, I had to have it. I read it, sitting in a chair in my bedroom, in less than an hour. I realized my mother and I had never discussed the book, and in that moment, it seemed I had robbed us both of something we deserved. I called her immediately and we spoke about it for hours. “You should teach this, share this,” she said.

Not many years ago, I taught Elie Wiesel’s Night to my high school students. I found a single Spanish copy in a small bookstore in Chula Vista, where the owner held his hand over his heart and told me we were lucky to have this novel for our class. As I was leaving, he gripped my hand and repeated himself and I knew he was telling a truth. Students read the text, both in English and Spanish. Many cried, many were angry, many wanted to know more, many wished there was less to know. None, however, were surprised. This was perhaps the greatest revelation of all. As a class we read the text, visited the Museum of Tolerance, and students opted to write to Mr. Wiesel. Many students received personal letters from Mr. Wiesel. Not pre-written stock letters, but letters directed to them, answering their questions, encouraging them to learn more, to be advocates themselves.

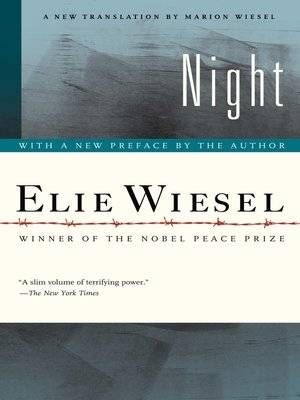

This year, I have found myself desperate to be lost in worlds that aren’t my own. Worlds of post-apocalyptic struggles and dysphoric landscapes. Worlds created by languages I have never learned and cultures I appreciate. Worlds of tepid relationships and resilient, gritty personas. This year I have seen innumerable social media posts reminding me that when we blink, horrific histories repeat themselves. This year, I stood in the bookstore, my fingers ghosting over the most famous cover of Night, and chose to ignore the sign centering the table: #resist. That night, I walked away.

Tonight, though, I rush hurriedly back to the beginning, the way one does when they have stumbled upon a plot twist and desperately thumb backwards through the pages, trying to connect the dots. Trying to see how something they felt all along, but never believed existed, could have begun under their watchful eyes. Tonight, I will read Night. I will retrace the dots that have long been connected. Tonight, I choose to read so that I will remember that we should never forget.