14 Must-Read Chinese Books in English Translation

China is the largest publisher of books, magazines, and newspapers in the world by volume. Chinese authors won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2000 and 2012. And as of September 2020, overseas readers of online Chinese literature exceeded 31.9 million people. So as readers, we really have no excuse for not reading Chinese literature in translation.

The Chinese literary tradition dates back to the 14th century BCE. Now, online literature is key to Chinese literature’s development and popularity. The internet has allowed Chinese authors to explore, express themselves, and experiment, particularly marginalized authors who are less likely to be traditionally published.

Chinese literature is increasingly available in English translation. The online platform, Webnovel, has uploaded more than 900 translated Chinese literary works since it was founded in 2017. And in 2005, the government began to sponsor translations of government-approved Chinese works, hoping to increase the number of books making it into the global literary world.

“Government-approved” is key. China’s state-run General Administration of Press and Publication screens all literary works to be published in print or online, and can legally censor and ban books, deny authors the right to publish, and shut down publishers. Book fairs held in China have had to exercise self-censorship, and foreign authors have discovered that their books were censored in their Chinese translations. The government still holds public book burnings, and the seizure and detention of publisher Gui Minhai is just one example of China’s repressive policies and actions when it comes to the publishing world.

Between the popularity of Chinese literature around the world and the political importance of China in the midst of global events today, it’s more crucial than ever to engage with Chinese literature in translation. Here, I recommend 14 works of Chinese literature for you to put on hold at your local library.

Please note that while I took great care to list content warnings where I could, things can fall through the cracks. Please do additional research on the recommended titles if needed.

The Last Quarter of the Moon by Chi Zijian, translated by Bruce Humes

In this beautiful work of historical fiction, a nameless narrator tells us about her long life as one of the Evenki, nomadic reindeer herders of the forests in northeastern China. Over the course of her life, the world intrudes on their lives, from the Japanese occupation and conscription to the increasing destruction of the forest and mountains. The drama of her family and her urireng, the love stories, the sudden deaths, all unspool in Zijian’s poetic and rich descriptions in our narrator’s storyteller voice. In a world where words carry the weight to curse and bless, where a Spirit Dance to heal a stranger comes at an incredible cost, where the reindeer lead and their clan follows, our narrator survives to write of grief, pain, and what it means when a culture is slowly lost to the grinding wheel of history.

Content warnings for sexual assault, anti-Indigenous sentiment and forced assimilation, miscarriage/abortion, domestic violence and abuse, suicide.

Chronicle of a Blood Merchant by Yu Hua, translated by Andrew F. Jones

A man named Xu Sanguan learns that you can sell your own blood for a good price — all you have to do is make sure to drink an inordinate number of bowls of water before you go. As he grows into a husband and father, part of a complicated family, he continues to return to the hospital through famine and struggle. This book is compelling for the twists and turns of its family turmoil, but also for the description of this blood-selling subculture and the questions it raises. What does it mean to be family — is it only defined by blood? And what if the only capital you have is your own body, your own energy, your own blood?

Content warnings for sex shaming, sexual assault, violence, suicidal ideation.

Red Sorghum by Mo Yan, translated by Howard Goldblatt

This Nobel Prize-winning novel tells of the devastating impact of war in the Northeast Gaomi Township over the course of three generations. As the Japanese occupy the region, taking over towns, and as the factions of rebels war amongst each other, death piles steadily higher around our protagonist, teenage boy Douguan. The novel is haunted by the realistic, brutal, tense, and bloody horror of war, and the trauma of those who survive it. But flashbacks give us the stories of Douguan’s family, of young lovers and his fierce, strong grandmother, of secret wine ingredients, affairs, and hope. It’s a devastating book but with seeds of love scattered throughout.

Content warnings for body horror, gore, violence, animal death and killing, suicide, rape.

The Day the Sun Died by Yan Lianke, translated by Carlos Rojas

One evening in early June, in a small Chinese town, Li Niannian notices that something is wrong. Everyone should be going home, heading to sleep. But instead, they’re all wandering in the darkness — sleepwalking. And over the course of one night, these sleeping townspeople will fall into chaos: secrets revealed, violence unleashed, past hurts unearthed. Lianke’s novel is a dystopian tale meant to challenge the “Chinese dream” promoted by President Xi Jinping, parodying the sunny vision of the government of what the Chinese people believe, contrasting it with the shame and madness of what’s unearthed in the darkness of night as Li Niannian and his father try to wake up their town.

Content warnings for suicide, violence, ableism.

Love in a Fallen City by Eileen Chang, translated by Martin Merz and Jane Weizhen Pan

This book appears on the Powell’s list “25 Books to Read Before You Die: World Edition.” Naturally, the list caught my attention — it features some of my all time favorites, including works by Mikhail Bulgakov and Elena Ferrante. In these two short stories and four novellas, Eileen Chang writes of 1940s Chinese society, of women’s lives from being forced into marriage to divorcing and being forced back to their families. Chang writes women encircled in a deeply patriarchal, stifling society, all in beautiful prose, also touching on romance, class issues, and the conflict between tradition and modernity — old and new.

Content warnings for sexism/misogyny, forced marriage, ableism, emotional abuse.

That We May Live: Speculative Chinese Fiction by Dorothy Tse, Enoch Tam, Zhu Hiu, and Others, translated by Jeremy Tiang and Others

Back in March 2020, Two Lines Press launched the Calico Series, a book series where they ask translators what works English readers are most missing out on. That We May Live is the first book in the series, and features seven weird and speculative tales that will appeal to Karen Russell fans. Garden keepers cultivate giant mushrooms into skyscrapers; Dorothy Tse paints a surreal dark tale of stinky brew and women’s bodies. As with all short story collections, not every tale is going to be a hit, but the appeal of this collection is its introduction to new, exciting writers from China and Hong Kong, and their stories about disorientation, urbanization, sexuality, and alienation.

Content warnings for misogyny.

The Three-Body Problem by Cixin Liu, translated by Ken Liu

This Hugo Award-winning novel is quickly becoming a science fiction classic. A secret military project is trying to establish contact with aliens — and succeeds, accidentally prompting an alien invasion. In the midst of China’s Cultural Revolution, different camps form, conflicted on how to respond: should we welcome the beings and help them take over our failing, corrupt world, or should we fight them and protect ourselves? This immersive, bizarre story dives into everything from theoretical physics to virtual reality, and looks at what alien contact could mean for us, and what humanity has earned for its future — do we really deserve redemption? It’s uncanny, evocative, and strange, and the first in a series.

Content warnings for suicide, gore, child death, murder.

Beijing Comrades by Bei Tong, translated by Scott E. Myers

In this emotional, sexy, and engrossing tale, an arrogant playboy businessman falls for a working-class student named Lan Yu. In doing so, he has to confront his own internalized homophobia, fear, classism, and sexism. The book by Bei Tong was originally published online, and was radical in many ways — not only did it portray explicit sex scenes and a gay relationship set in late 1980s China, but Bei Tong (who wrote under a pseudonym) also wrote directly about the Tian’anmen Square protests and repression. There have been various edited and censored versions published since Bei Tong first put it online, but translator Scott E. Myers combines these versions into one unified story closer to the original.

Content warnings for violence, homophobic repression and language, internalized homophobia, sudden death, government repression of protests, and grief.

I Live in the Slums by Can Xue, translated by Karen Gernant and Chen Zeping

Can Xue’s works are famously surreal, strange, and amorphous. So her absurd short stories are probably the best place to try out her style. In this book, the characters flee and shift, trying to fit in, trying to find a place free of abuse, where they can be safe, in a world defined by scattered-ness, by lack of community, by inequality. A young man searches for a magic pond, a Kafka-esque rat-person tries to find peace, a magpie protects its partner from human neighbors. Can Xue’s pen name refers to the snow left over at the end of winter — she chose to write under a pseudonym to hide her gender while publishing her radical, experimental fiction.

Content warnings for abuse, classism, cannibalism, violence.

The Chilli Bean Paste Clan by Yan Ge, translated by Nicky Harman

The Duan-Xue family owns the lucrative Mayflower Chilli Bean Paste Factory in the small town of Pingle. Ruled by a terrifying matriarch, Gran, the family is nevertheless dominated by raucous, hard-drinking men who aren’t awfully good to their wives and find themselves occupied in petty rivalries. The granddaughter of the matriarch — who is in a psychiatric hospital — narrates Ge’s novel, weaving together bits of gossip and passed-down tales. As the family plans a big birthday party for Gran’s 80th, secrets and old dramas begin to emerge back into the light. Yan Ge based her novel on her own small town in the Sichuan province, giving it an air of reluctant authenticity.

Content warnings for alcoholism, sexism/misogyny, mental illness.

A Hero Born by Jin Yong, translated by Anna Holmwood

You’ve watched and loved works of the wuxia genre, though you might not know it: tall tales of honorable martial arts warriors fighting evil in spectacular battles. Jin Yong is one of the genre’s superstars — first published in 1950s Hong Kong, he is one of the most widely read Chinese writers alive. A Hero Born is the start to his magnificent 12-volume series, Legends of the Condor Heroes. Guo Jing, the son of a murdered patriot of the Song Empire, grows up within the army of Genghis Khan. Guided by the Seven Heroes of the South who swore to train him, Guo Jing is fated to return to China to fulfill his destiny and repel the invaders who have occupied his home. Despite selling more than 300 million copies in China, it took until 2018 to get this book translated into English.

To Live by Yu Hua, translated by MIchael Berry

I know — another book by Yu Hua. But I can’t help it! This novella spans history from the 1930s and the Second Sino-Japanese War to the civil war to the 1960s cultural revolution — all in just 200 pages. The spoiled son of a landlord, Xu Fugui, squanders his family’s entire fortune. Over the course of his life, Fugui will go on to become a hardworking farmer, struggle through forced conscription into the Nationalist Army during the Civil War, and watch his loved ones slowly die through years of hunger and the hardships of the Cultural Revolution. The book was voted one of the most significant and influential novels of the 1990s by Chinese critics and editors, and it was translated into English in 2013.

Content warnings for suicide, torture, hunger, classism, domestic abuse, child death.

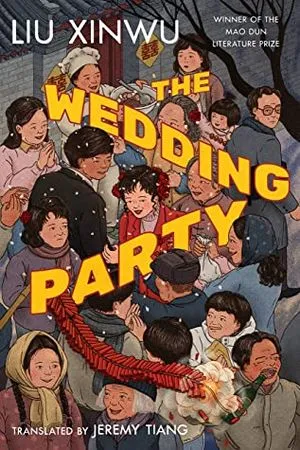

The Wedding Party by Liu Xinwu, translated by Jeremy Tiang

It’s December 1982, in the midst of the cultural revolution in Beijing, under the shadow of the mythic, ever-standing Bell and Drum Towers, and Auntie Xue’s son, Jiyue, is getting married today. Maybe Jiyue doesn’t fully know what he’s getting into. And maybe the chef isn’t ready to take this on. Maybe the bride is anxious. And maybe there are people preparing to crash the wedding. But somehow, this wedding is certain to go off without a hitch. Right? Out of this one Beijing courtyard in the chaos of wedding preparations, an epic of intertwined stories unfolds. This novel was first serialized in 1984 and won the prestigious Mao Dun Literature Prize. And yet again — despite being popular since the 1980s, it took until 2021 for us to get this superb English translation.

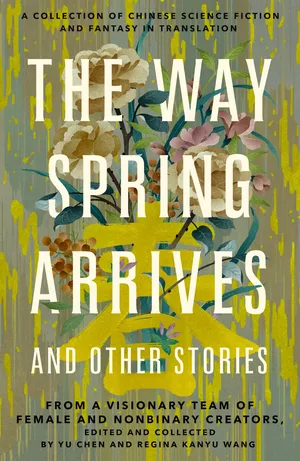

The Way Spring Arrives and Other Stories: A Collection of Chinese Science Fiction and Fantasy in Translation from a Visionary Team of Female and Nonbinary Creators, edited by Yu Chen and Regina Kanyu Wang

This collection is an immense blessing — impossible to put down and full of incredible stories. In “Baby, I Love You” by Zhao Haihong, translated by Elizabeth Hanlon, a man persuades his partner to have a baby so that he can improve his holo-game and advance his career. In “The Stars We Raised” by Xiu Xinyu, translated by Judy Yi Zhou, the children of a village gather and play with the strange sparkling stars that haunt a village, and one bullied boy insisted he’s managed to train his. The stories retell and play with myths and folklore, write of repression, imperialism, and genocide through the lens of speculative fiction. Curses, disillusionment, light, water, cascade through the stories, while the essays give vital and fascinating insights into the world of Chinese SFF and its sub-genres and communities.

Content warnings for sexual harassment, body horror, violence, genocide.

Want more books in translation content? I have lists for you of books in translation from Catalonia, Argentina, France, Mexico, Central Africa, Japan, Southeastern Europe, and Brazil. If you have recommendations or requests for future lists of books in translation, or if you want me to know about a book I missed, please let me know on Twitter.