Book Banners Don’t Know What a Book Ban Is

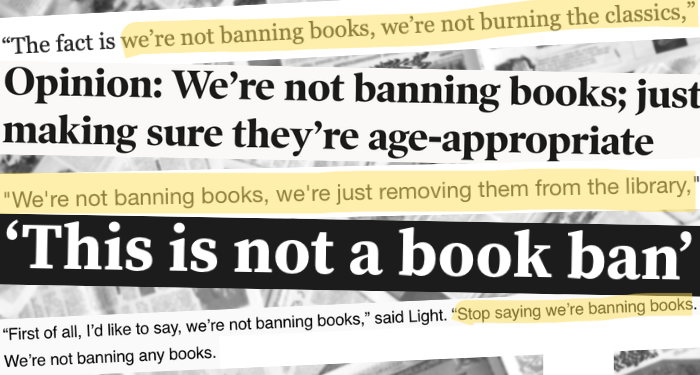

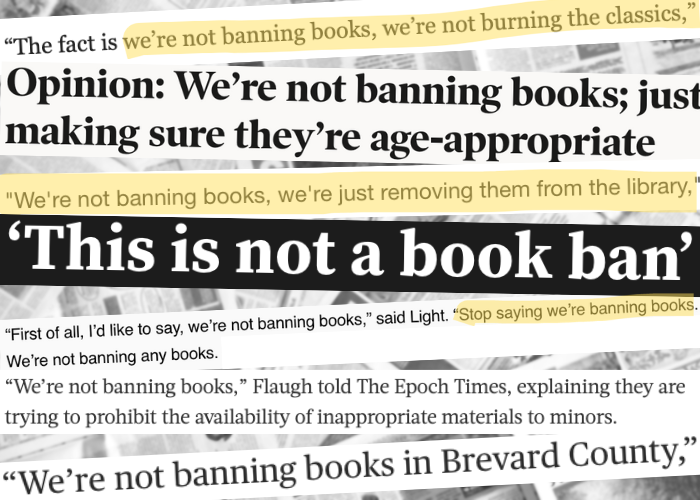

If you open up any one of hundreds of news stories of rightwing “parents’ rights” groups trying to have book removed from schools for having queer characters or mentioning the existence of sex, you might notice a common refrain: “We aren’t banning books. Anyone can buy it on Amazon if they want.” There are so many problems with this sentiment, but the first one is that is has become abundantly clear that book banners don’t actually know what a book ban is.

It seems like everyone wants to ban a book, and no one wants to be a book banner.

But the truth is that a book ban isn’t the same as making it illegal to buy or sell that book in the entire country. It’s not putting a book title in the same category as selling heroin or looking for elephant tusks on the black market. It’s absurd to shift the goal posts by trying to say that book banning is an on/off switch, where as long as someone, somewhere, somehow can access the book, it’s never been banned.

So what actually is a book ban? According to the American Library Association, “A challenge is an attempt to remove or restrict materials, based upon the objections of a person or group. A banning is the removal of those materials.” A book does not have to be removed everywhere to be banned. Usually, book bans happen on a local level: a book is banned from a school, a district, or — in circumstances that are unfortunately becoming less rare — a state.

This definition makes sense intuitively. After all, if someone is banned from a business, they don’t immediately have to leave the country. We can ban things on a numbers of levels: it just requires someone of some authority to enforce it, whether that’s a school principal or a politician. There are different degrees of book bans: a teacher may ban an author’s books from being allowed in their classroom because of their personal distaste for their work, or a state representative could try to have whole categories of books (queer books, antiracist books, sex education books) banned from all schools in their state.

In some ways, it’s encouraging that this wave of book banners is so uncomfortable having their action labelled accurately. It shows that even in that extreme corner that thinks that Heather Has Two Mommies is a kind of pornography and that being taught about Ruby Bridges is “reverse racism” — even they know that the people banning books are not generally the good guys.

It’s important that we not let them sidestep this reality, though. If it was about parental choice, then they wouldn’t be calling for these books to be removed from school and public libraries, which prevents families from making their own choices. Instead, they want to impose their worldview — which is overwhelmingly white, cis, and straight — on everyone. This is why it’s censorship and it’s why it’s a book ban.

Parents have always had the ability to control the media their child consumes, but they can’t expect schools and libraries to mirror that and enforce it for them. That responsibility lies with the parent, especially because each family has their own definition of what is age appropriate. Libraries and public schools have a different mission: to represent and serve their entire community, including people of color, queer people, and trans people.

Building a book bonfire is not the only way to ban a book, and neither is making it illegal on a federal level — which would be a first. Book bans can be subtle and quiet, occurring in a single classroom, or they can be contentious affairs yelled over during a library board meeting, or they can be handed down by state representatives and enforced with lawsuits.

It’s also disingenuous for this group to claim they’re not trying to make these books illegal, considering the rise in lawsuits against anyone involved in carrying them, including suing a bookstore for carrying Gender Queer and A Court of Mist and Fury. It’s not necessary to make a book illegal in order to ban a book, but this wave of book banners is certainly not above exerting legal pressure in order to try to remove books from schools, libraries — and even bookstores.

To the book banners who are busy scouring books for one scandalous line in hundreds of pages, or printing out comic panels to wave at school board meetings, or otherwise lobbying to remove books from readers’ hands, I wish I could show you the beauty, hope, and life-saving effects of those books. I wish you could understand that the world offers so many incredible ways to be a person, and that these books help kids feel less alone. I wish you valued trans kids’ lives over your own comfort. I wish you saw the necessity of tearing down injustice to build a better world. I wish you would use all that anger and energy to help make things better instead of painting over the problems that exist. I hope you embrace the whole abundant spectrum of people your kids may grow up to be. I wish you saw that the diversity shown in these books is what makes communities stronger and a better place to live. I hope you see that some day.

In the meantime, though, I have a request: own the book ban label. And if it makes you uncomfortable to call what you’re doing book banning, explore that feeling a little longer, and see if that leads you somewhere different.

If you want to fight book bans and censorship, check out Book Riot’s anti-censorship tool kit. To stay up to date with censorship news, subscribe to our Literary Activism newsletter.