Reimagining Folk and Fairy Tales (with Kink, Joy, Nudity)

Reinterpreting myths, fairy tales, and folk tales is way more than a cottage industry—a castle industry?—in publishing these days. From literary fiction (The Tiger’s Wife) to YA (Robin McKinley’s books, Runemarks) to graphic novels (the Fable series, The Sigh) to humor (Gods Behaving Badly), authors are picking up and reimagining bits and pieces from millennia of human story-telling. This is, of course, not entirely new; as long as there have been stories there have been reinterpretations of them. But the purposefulness and the politics do seem to have shifted in interesting ways over the past several decades, as feminist and LGBT/queer authors rethink these stories for a new world.

Words on the page aren’t the only place this is happening. “Turning the tables,” an exhibition currently on display in Urbana, Illinois, is artist Eszter Sápi’s playful efforts to reclaim and rethink the myths and tales she grew up with. Sápi’s drawings aren’t books, but they do offer us a useful opportunity to think through the tools and methods authors use when they reimagine folk and fairy tales. After seeing Sápi’s show, my way of thinking about what authors like Téa Obreht or Marjane Satrapi are doing has shifted. So I thought I’d share some of her work here, in hopes that it might spark something in you, as well.

Sápi was raised in Nyíregyháza, Hungary, and almost every night, right around bedtime, she sat down in front of the TV to watch the animated versions of traditional Hungarian folk tales that aired on national television. “For the longest time, they tricked me,” she remembers. They taught her that women’s pleasure was frightening, that economic inequality was natural, that violence was a just tool of the powerful.

But now, years later, a lesbian artist living in Illinois, Sápi is revisiting these tales, rereading and reimaging them in peculiar ways. Sápi’s drawings pull characters out of context, taking them out of the stories that made violence and inequality seem inevitable. Rearranging and recontextualizing the characters, she both disrupts and opens up the stories, revealing the strange, queer themes that had been hiding there all along.

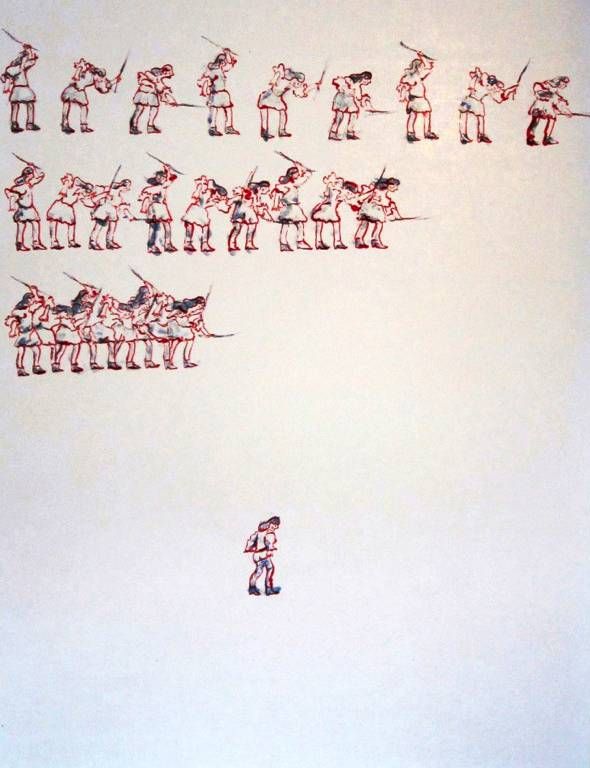

For example, a lot of the old folk tales were, as she puts it, “pretty kinky.” Indeed, spanking and whipping appear again and again in the stories she grew up with. But where consensual fun is one thing, coersive violence is another. So, in several of the drawings in her new show, Sápi takes an iconic scene—of castle guards being tricked into taking a whipping

From an animation you can watch here.

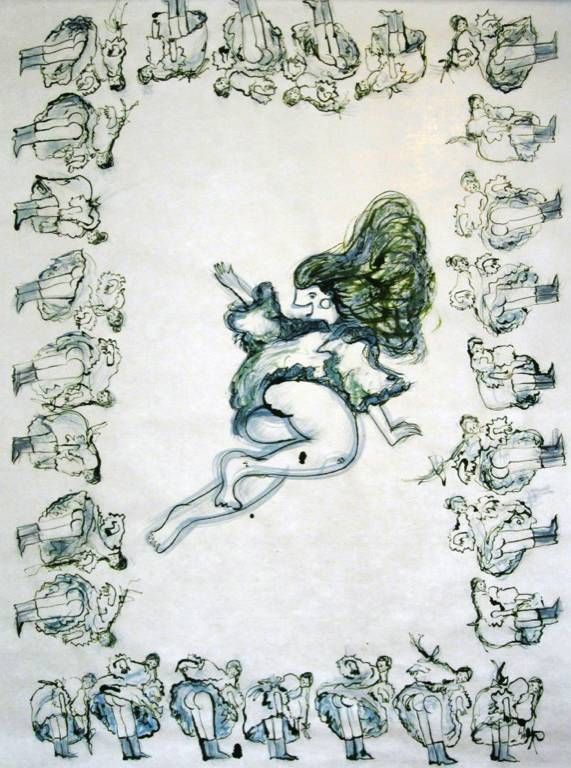

—and decontextualizes some elements and repeats others. Here’s a powerful example:

Drawing and photograph by Eszter Sápi

There’s a tension here that’s central to many reimaginings of folk tales and fairy tales, between the momentum of the story and the possibilities of its retelling. In the top three lines, the figure with the switch strikes and strikes but never hits, the repetition emphasizes the violence but at the same time highlights its futility. And below, the traditional object of the whipping lowers his pants, but, at a distance from the switch, he reads less complacent and more, well, cheeky.

This is, I now better understand, what authors do when they take a familiar tale and reinterpret it: they rearrange characters and plots, creating gaps and spaces where there didn’t seem to be any distance, any reprieve, any uncertainty. The princess no longer must marry the prince, the war no longer must produce a hero, the dead no longer keep to their graves—contingency and possibility erupt on the page and something new is built of old bones.

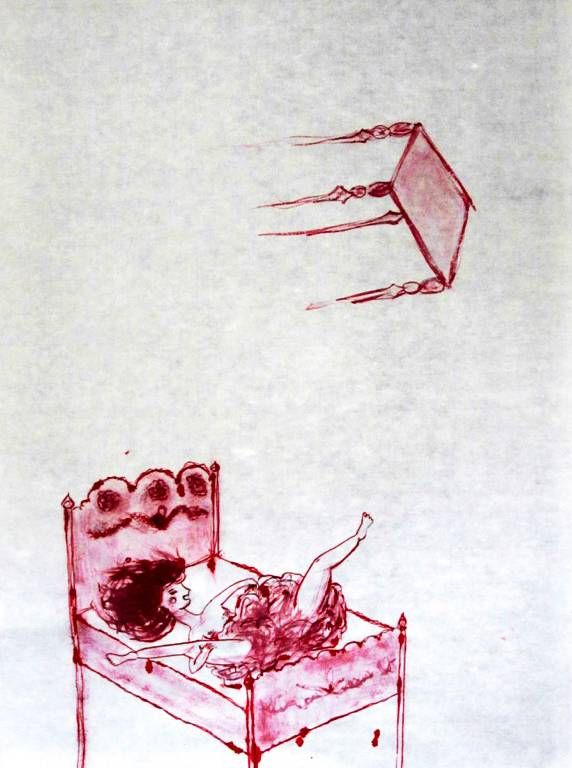

In another drawing, Sápi takes on another common feature of the folk tales: exposed female bodies. In tale after tale, women were tricked into disrobing or were bent over for a spanking or used nudity to convince kings to give them treasures. (As Sápi muttered at one point during the opening of her show, “That’s a lot of nudity to watch with your family when you’re a kid.”) In this piece, Sápi excavates joy—look at that grin!—and power from the tales’ often troubling depictions of women:

Work and photograph by Eszter Sápi

Like Gail Carson Levine or Marion Zimmer Bradley, Sápi confronts head-on the often violent misogyny of older stories and then reworks, rethinks, reimagines them into something glorious and full and powerful.

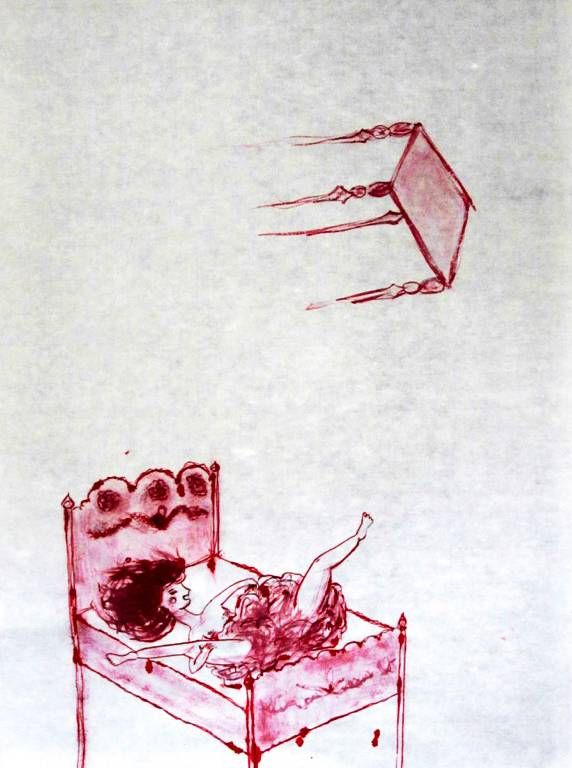

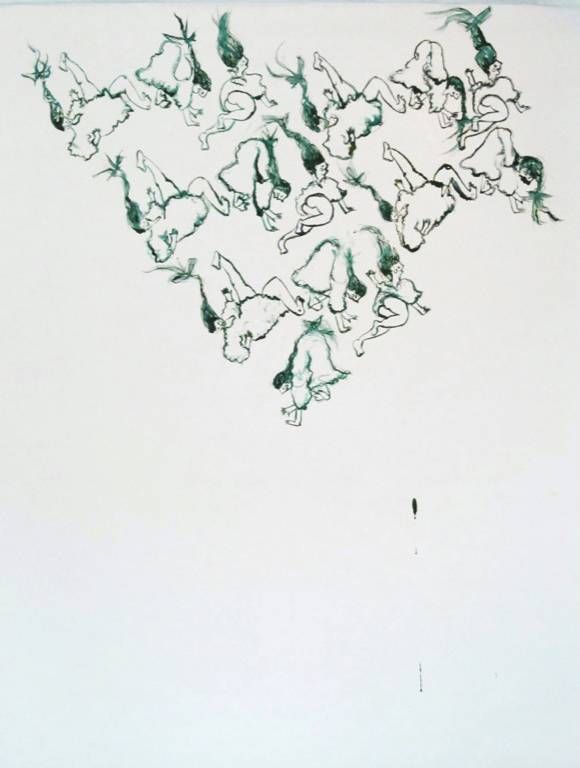

In another piece, Sápi reworks an original scene where a man forces open a woman’s legs yelling, “Come out, devil, so I can get in!”

Yes, this was a cartoon for children. You can see the animation here.

In her adaptation, the man is gone, and the woman is free to experience pleasure and desire and happiness and independence without the inevitable intercession of men and their demands. “So, the woman with the continuous orgasm can enjoy herself,” Sápi explains, “without shame and without having to worry about some dude who is on an unrequited quest to save her”:

Work and photograph by Eszter Sápi

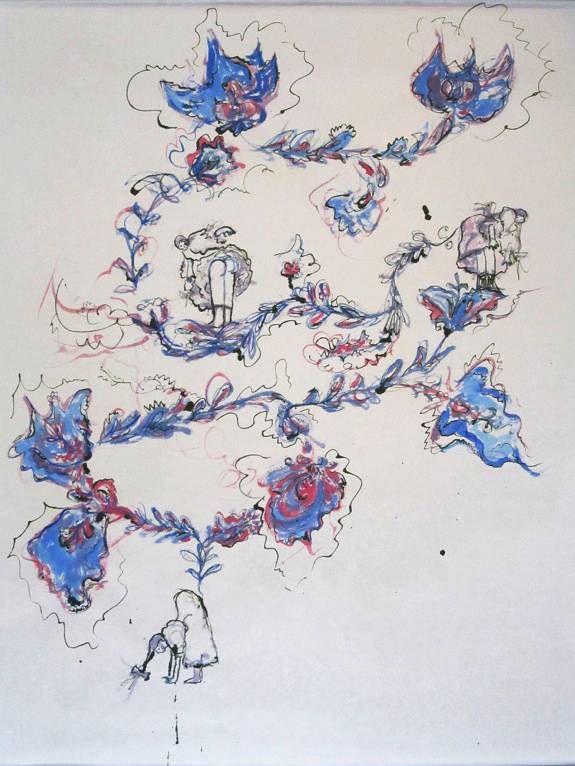

Speaking of power and joy, I’ll leave you with a piece that plays with the story of a girl who outwits a king, and another where the threat of devil-induced pleasure is redrawn as a cluster of women happily enjoying themselves.

Work and photograph by Eszter Sápi

Work and photograph by Eszter Sápi

Sápi’s work, as you can see, is gleeful and unsettling in equal measure as only folk and fairy tales can be. So next time you pick up The Tiger’s Wife, or Fable, or The Sigh, I urge you to keep Sápi and her figures in mind. Let them dance, uncontrolled, a bit wild, through your mind. The pages will reward you for it.

_________________________

Sign up for our newsletter to have the best of Book Riot delivered straight to your inbox every two weeks. No spam. We promise.

To keep up with Book Riot on a daily basis, follow us on Twitter, like us on Facebook, , and subscribe to the Book Riot podcast in iTunes or via RSS. So much bookish goodness–all day, every day.