SPEAK and Steubenville: Can YA Help?

Books change lives! Or so we always say. Yet this consensus is typically drawn from personal experience alone. We know it’s true because–well, it’s happened to us! But when it comes to censorship battles, or an age of education based on standardized test scores alone that’s changing the language arts classroom as we know it, hard data is really what we need on our side when it comes to standing up for important books.

Books change lives! Or so we always say. Yet this consensus is typically drawn from personal experience alone. We know it’s true because–well, it’s happened to us! But when it comes to censorship battles, or an age of education based on standardized test scores alone that’s changing the language arts classroom as we know it, hard data is really what we need on our side when it comes to standing up for important books.

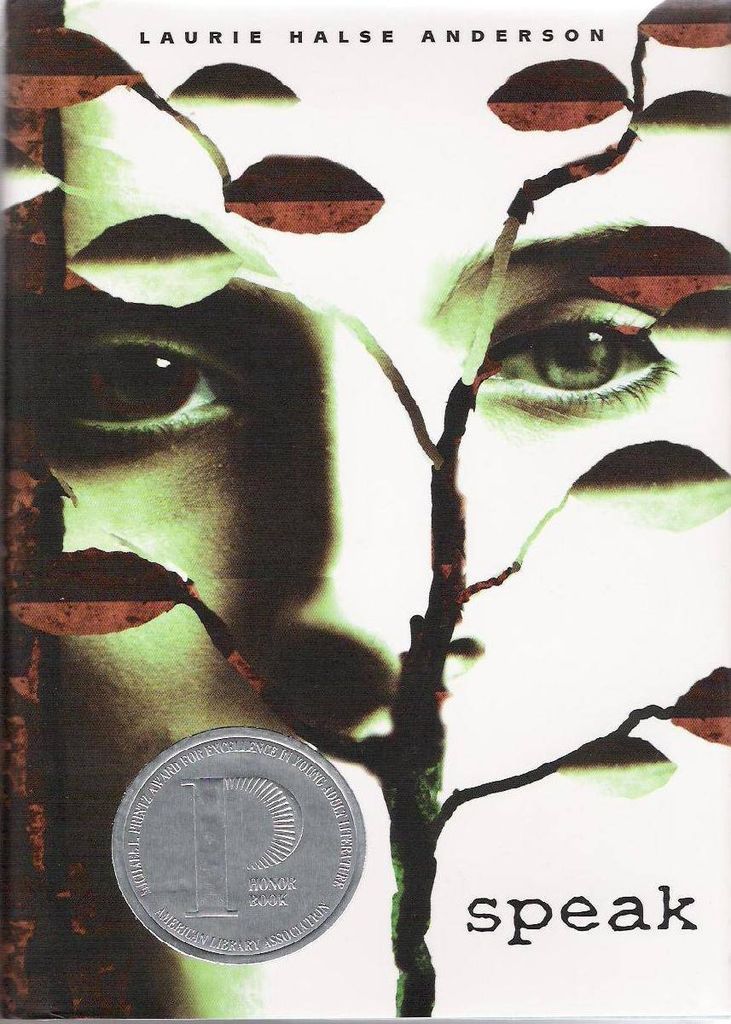

So thank goodness one awesome doctoral student’s dissertation last year did just that! Victor Malo-Juvera’s 2012 study measured students’ “rape myth acceptance” before and after reading Laurie Halse Anderson’s Speak. For those who aren’t familiar, Speak enters the brain of a girl who goes silent for a year after she’s raped at a party. An exceedingly excellent book originally published in 1999, it’s considered a YA classic and is frequently taught in schools.

Anderson herself remains a stalwart advocate for sexual assault education, an issue that hasn’t necessarily changed in importance since Steubenville, but whose importance has perhaps just suddenly, and disturbingly, become clearer to many in America. In an excellent recent interview with Jen Doll at the Atlantic, Anderson explained:

“I was shocked when I realized how ignorant boys are about this. It became clear in 2002, after five years of pretty heavy school visits, and people putting the book into the curriculum. In every single demographic—country, city, suburban, various economic classes, ethnic backgrounds—I’d go into a class and talk about the book. And usually by the end, a junior boy would say, ‘I love the book, but I really didn’t get why she was so upset.’ I heard that so many times. The first couple dozen times I sort of freaked, and then I got down from my judgmental podium and started to ask questions. It became clear that teen boys don’t understand what rape is.”

Teens are so often not explicitly taught things that adults assume they already know. With no other options, they frequently buy into the myths that wider society helps to propagate, such as the varied, seemingly unshakable myths about rape. Anderson cites the belief many still hold that rape can only be committed by “a stranger in the bushes with a gun,” while Malo-Juvera in his dissertation boiled his research down to two rape myth factors: “She wanted it,” and “She lied.”

Cold, hard data. There’s been so much talk post-Steubenville about changing our rape culture. Can books like Speak actually help? Here’s my brief summation of Malo-Juvera’s dissertation, so you don’t have to read the 180+ pages of it yourself:

-

While most adolescents begin dating in middle school, most sexual assault conversations don’t happen until high school, if at all, with the largest amount of rape prevention education still taking place at the collegiate level. (And we should remind ourselves that many American students do not attend college.) The way it’s enacted is also often through didactic lectures or other short-term activities in health or elective classes, as opposed to the academic core subjects that reach all students. Programs are also often led by outside experts as opposed to regular teachers. This can be problematic, sometimes ending in a “backlash” effect where rape myth acceptance is actually higher than it was previously, when teens–particularly boys–react defensively. Think about it: when you hold a set of beliefs, especially as a young person, and a stranger or person of authority simply tells you, “You’re wrong,” how often does that actually move you to change your mind?

-

Malo-Juvera also cites the correlation between high rape myth acceptance and the proclivity to become a sexual assault perpetrator in the future, which is perhaps a “duh” moment, but still important. Teens are also at particular risk for these behaviors; by one study, a 14-year-old is four times more likely to be sexually assaulted than an adult.

-

Malo-Juvero argues that the reading of novels, and novels that are directly relevant to a majority of students’ lives, both raises interest in reading and impacts students’ own morals and beliefs by creating empathy. (No way!) This is mostly based on Rosenblatt’s reader response theory.

The study encompassed seven diverse 8th grade classrooms, where the majority of students were Hispanic/Latino, who studied the novel over five weeks. The data was primarily taken from pretest and post-test surveys using the Rape Myth Acceptance Scale, a previously vetted methodology. A control group of other students reading Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar in the same time period also took the pre- and post-tests.

The results confirmed almost all of Malo-Juvero’s hypotheses: reading Speak significantly lowered rape myth acceptance among students, with more dramatic results among boys than girls, this mainly due to the fact that girls largely already had a lower rape myth acceptance rate prior to the reading. It was most effective in reducing the factor of “She Wanted It,” as this is the type of myth that is most directly dealt with by Melinda, the protagonist of Speak.

The “backlash” effect of some students’ rate myth acceptance actually increasing, as seen in other studies of rape education, was eliminated.

He also stressed the importance of frequent Socratic seminar type discussions throughout the unit in addition to written responses, wherein the teachers allowed both anti-rape myth and pro-rape myth views to be shared. And both teachers involved in the study reported pro-rape myth views were shared in their classrooms, such as “No doesn’t always mean no.” But as he says, “The importance of the beliefs of one’s peers cannot be overstated for adolescents and allowing participants to hear that rape is not socially acceptable to their peers appears to be a powerful attitudinal change agent.” Essentially: teens don’t want to listen to you, adults. But they will most definitely listen to each other. (And to protagonists in books they can relate to.)

He cites the need for additional research to be done after these initial findings, including recurring testing to see if the effects of reading the novel last over time, as well as repeating the test among different age levels and different demographics.

Malo-Juvera also states that, to his knowledge, this was the first research study of its kind in specifically studying the social effects of YA novels. He encourages similar studies to be done using topics such as bullying, homophobia, racism, misogyny, and so on. You hear that, academia? Get on it.

You can read Malo-Juvera’s full dissertation here. You can also keep track of Laurie Halse Anderson’s current fundraising efforts for RAINN (Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network) with the Twitter hashtag Speak4RAINN. A useful list of further YA novels that deal with sexual assault can be found here.

_________________________

Sign up for our newsletter to have the best of Book Riot delivered straight to your inbox every two weeks. No spam. We promise.

To keep up with Book Riot on a daily basis, follow us on Twitter or like us on Facebook. So much bookish goodness–all day, every day.