Our Reading Lives: Death, Here is Thy Sting

This is a guest post by David Abrams. David is a novelist, short story writer, reviewer, and book evangelist. His novel about the Iraq War, Fobbit , is forthcoming from Grove/Atlantic in 2012. He blogs about books at The Quivering Pen. Follow him on Twitter @davidabrams1963

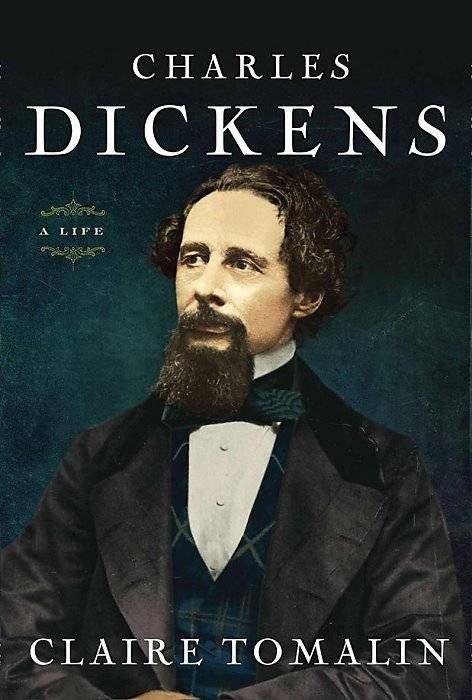

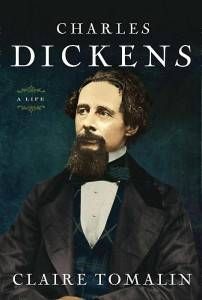

As I turned the final pages of Charles Dickens: A Life, my hand went slower and slower, hesitant to take the corner of the page in my fingertips and move it right to left. I was prolonging my trip through Claire Tomalin’s biography because, you see, I had reached the point where the book could more properly be called Charles Dickens: His Death.

I was filled with sadness for a man who had been dead 142 years, but for the space of nearly 500 pages, he had been kindled to life again. Rejuvenated, he bustled through the Old Bailey, taking notes as a young journalist; he moved his pen across 9 x 7 inch pages at fevered speed, dipping the nib into the inkwell and spattering drops as he created Wackford Squeers and Uriah Heep and Sairey Gamp; he hurried through the London suburbs on one of his legendary walks, his legs carrying him across the land, his England, at speeds up to five miles per hour. He smoldered, he sparked, he burst into flame.

I was filled with sadness for a man who had been dead 142 years, but for the space of nearly 500 pages, he had been kindled to life again. Rejuvenated, he bustled through the Old Bailey, taking notes as a young journalist; he moved his pen across 9 x 7 inch pages at fevered speed, dipping the nib into the inkwell and spattering drops as he created Wackford Squeers and Uriah Heep and Sairey Gamp; he hurried through the London suburbs on one of his legendary walks, his legs carrying him across the land, his England, at speeds up to five miles per hour. He smoldered, he sparked, he burst into flame.

But now, by page 390, his energy was spent, his body weakened by gout, bunions, (possibly) gonorrhea, heavy drinking, and strokes. Of course I knew he would die, of course I knew it. But as I approached that moment on June 8, 1870 when he collapsed for the final time, I was sad. I turned the pages at a funereal pace.

I looked at my wife sitting across the breakfast table from me. “This is silly, isn’t it? Mourning someone already in the grave.”

My wife, in her imperturbable and honest-to-a-fault manner, said, “Yes.” I’m sure she wanted to add, “You should be ashamed of yourself, a grown man like you,” but she held her tongue.

This is the effect of good literature, though—to make us mourn the imaginary and the historical figures of our books. Measured against this, Tomalin’s biography is good literature, the finest kind of engagement with language that can make a grown man collapse in a puddle at the thought of a life ending. Such, also, is the power of Charles Dickens’ hold over me, over all of us. Yes, he was flawed—he was the best of men, he was the worst of men—but he was also a genius, a supra-human being. To read of his death is to feel the loss all over again as his fans surely must have felt in 1870.

In my hand, the pages turn slower and slower. And then, the Moment arrives:

[His daughter] Georgina said that Dickens came to the house in the middle of the day for an hour’s rest and to smoke a cigar, and then went back to work in the chalet, contrary to his usual habit, returning to the house in the late afternoon to write letters and entering the dining room at six, looking unwell. He sat down and she asked him if he felt ill and he replied, “Yes, very ill; I have been very ill for the last hour.” On her saying she would send for a doctor, he said no, he would go on with the dinner, and go afterwards to London. He made an effort to struggle against the fit that was coming on him, and talked incoherently and soon very indistinctly….[Georgina said] “Come and lie down,” and [he replied] “Yes, on the ground,” as he collapsed on the floor and lost consciousness. Haunting last words. Now at last the core of his being, the creative machine that had persisted in throwing up ideas, visions and characters for thirty-six years, was stilled.”

I can’t bear it. I turn my head away from Tomalin’s book. I am overcome.

I suppose I’ve been playing the sentimental fool. This is, as my wife would say, conduct unbecoming. But I think Dickens would approve—and not just because it would swell his ego, but because he bathed in sentiment every day. His characters were larger than life. Hell, his life was larger than life.

Exhibit A: Sydney Carton. While working my way through the final pages of Tomalin’s biography, I have also been reading the closing chapters of A Tale of Two Cities. As Dickens draws near to his hemorrhage, the noble Carton approaches the guillotine and those most famous of last lines: “It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known.” (Contrary to popular memory, he doesn’t actually utter these words as he mounts the scaffold—Dickens says if Sydney Carton had been given a chance to speak, this is what he would have said.)

In Charles Dickens: A Life, Tomalin writes this about the end of A Tale of Two Cities: “The climax of the action is preposterous and deeply sentimental, but the tension is so built up that Carton’s famous last words…make their effect on all but the most determinedly stony hearts. This is Dickens the showman, amusing his people and drawing their tears.”

Charles Dickens knew how to wring words of their last drop of emotion. Over the years, many a copy of A Tale of Two Cities has had its last twenty pages water-damaged by tears. And now it is my turn.

Dickens is dying, Sydney Carton is dying. I hold their deaths in my hand. A double whammy of melancholy. Gee, great! Why don’t I just throw Brian’s Song into the DVD player while I’m at it?

But really, why is it like this? Why are the most susceptible among us wired to cry when Dickens dies, when Little Nell is carried to heaven on the arms of angels, when Gale Sayers lifts a weak arm from the hospital bed and clasps Brian Piccolo’s hand, when Old Yeller dies, when Anna Karenina is ground beneath the wheels of the train, when Marilyn Monroe and Princess Diana are turned into candles in the wind, when Dr. Mark Greene succumbs to his brain tumor on ER? Because, dear sobbing friend, we have been skillfully manipulated. Dickens did it, Elton John did it, and even Tomalin does it in the careful, stage-managed placement of words to describe the end of Dickens. After his collapse, he never regained consciousness, but lingered on for several hours until his final moment—which, as Tomalin describes it, is so “preposterous and deeply sentimental” it can only be true: “Soon after six in the evening Dickens gave a sigh, a tear appeared in his right eye and ran down his cheek, and he stopped breathing.”

More than 140 years later, my nose stings and the corner of my own right eye grows damp. My wife threatens to slap me, but I shake my head. I have no one to blame but myself, my weak resolve, my thin-walled tear ducts. Dickens is dead, long live Dickens!