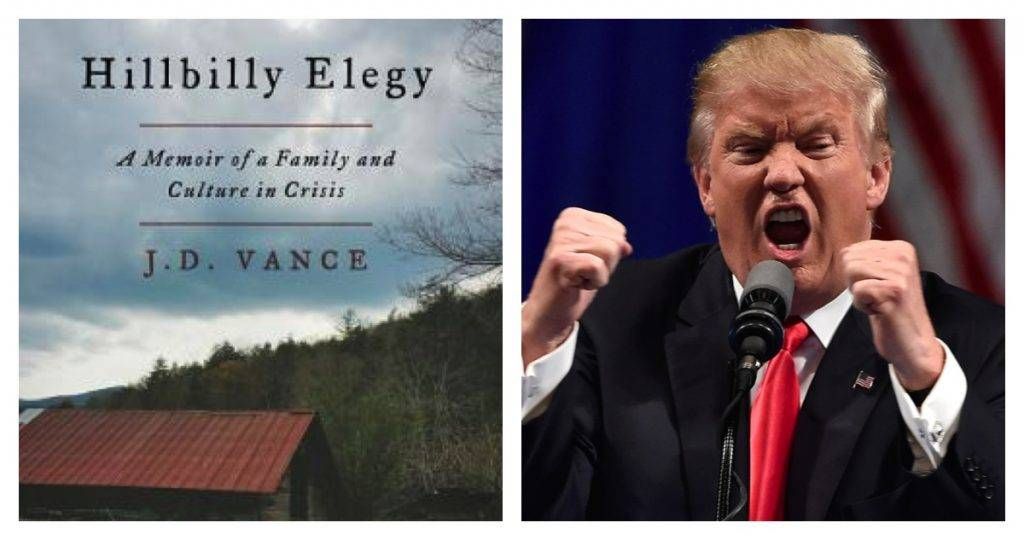

Lies, Damn Lies, and HILLBILLY ELEGY

Sometimes, a book makes its mark only retroactively, once personal circumstances – or, say, presidential elections – change things suddenly and irrevocably. J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy is such a book.

Published earlier this year to considerable acclaim, Vance’s book purports to be an analysis of the decline of the so-called white working class, a group which, in the days following Donald Trump’s election, has become the most-discussed voting subgroup in the country. In reality, Hillbilly Elegy is two books: one is an incredibly compelling memoir about family and addiction, and the other is a clumsy social commentary that cherry-picks its sources and presents anecdotal evidence as a revelatory peek behind the curtain of the rust belt’s and Appalachia’s economic decline.

That’s just my reading, however. In the days since the presidential race ended, Hillbilly Elegy has been praised far and wide as nothing short of a prophecy that predicted Donald Trump’s rise and gives Democrats their road map to connecting to a broader swath of the electorate. Vance’s interviews haven’t done much to discourage this assessment. “We have to rebuild the broken pipeline to the middle class,” he told The Columbus Dispatch, echoing the popular (but dangerous and increasingly hard to swallow) post-election sentiment the economic anxiety of working class white people was the biggest factor in the election.

That’s just my reading, however. In the days since the presidential race ended, Hillbilly Elegy has been praised far and wide as nothing short of a prophecy that predicted Donald Trump’s rise and gives Democrats their road map to connecting to a broader swath of the electorate. Vance’s interviews haven’t done much to discourage this assessment. “We have to rebuild the broken pipeline to the middle class,” he told The Columbus Dispatch, echoing the popular (but dangerous and increasingly hard to swallow) post-election sentiment the economic anxiety of working class white people was the biggest factor in the election.

That anxiety is certainly one of the focuses of the book, and there’s no doubt that in the places where Vance grew up, the ones he writes at length about in Hillbilly Elegy, it’s prevalent. One of those places — Jackson, Kentucky — is about a 90-minute drive from where I sit writing this, and believe me when I say that it, along with most of the Eastern third of my state, feels about as ignored by the political class as a place can be. In 2014, Kentucky had the third lowest household income in the U.S., and poorly-performing schools, the loss of coal jobs, and the ravages of opioid addiction have dealt crushing blows to the region.

As Vance points out repeatedly throughout Hillbilly Elegy, the people of Jackson and places like it often become stuck in a depressive cycle. His own family’s struggles — his mom has battled addiction for years and alcoholism and poverty were heavily present throughout his childhood — are a testament to that, even though by Vance’s own admission he was relatively fortunate. And when his book uses personal experience to shine a light on the effects of these struggles, it’s frequently captivating and thoughtful. But when Vance uses his personal experience to make broad proclamations about social ills, he displays an incredibly amateurish level of reasoning for a dude who graduated from Yale’s law school.

For example: wanna know how Vance knows that the welfare system doesn’t work? While working in a grocery store, he saw people poorer than him using their food stamps to buy irresponsibly fancy foods.

Now, is the U.S. welfare system flawed? Surely. But it’s irresponsible to use an anecdote from his time as a grocery clerk to serve as the only evidence he needs to diagnose the shortcomings of programs that piles of policy experts haven’t been able to crack in 50 years on the case.

This kind of intellectual laziness is a bummer coming from Vance, since it’s clear that — despite his book’s shortcomings — the guy is trying to fairly represent an underrepresented, often mocked region and find the best in the people who populate it, even when that’s not easy to do. Unfortunately, the laziness hasn’t stopped with Vance. Instead, it’s become standard operating procedure for the many political pundits and social commentators using Hillbilly Elegy to characterize Trump’s victory as something besides an affirmation of the racist, misogynist, homophobic, xenophobic tenor of his campaign and subsequent personnel decisions. The voters of the white working class have been forgotten, they allege, and their disillusionment with the both the government and the political process led them to, as Vance has put it, “shake things up.”

But as many have noted, even if a given voter’s reasoning for choosing Trump was not rooted consciously in racism, misogyny, homophobia, xenophobia, etc., all of those components of Trump’s campaign were plainly visible to voters for the better part of 18 months, and so — at best — a vote for Trump is an admission that none of those things (and the threat that the language and actions of the candidate pose to already marginalized groups) mattered more than personal economics.

Many praising Hillbilly Elegy, however, are using the book as a shield against that criticism while conveniently ignoring the fact that the poorest non-white voters (who surely suffer from similar levels of economic anxiety) did not turn out for Trump, generally speaking.

Don’t listen to the chorus of people using Vance’s book to dismiss the widespread prejudices made apparent by the election. Because while it’s true that Appalachia has a lot of problems that shouldn’t be ignored, there’s no way to honestly claim that it’s just about the Benjamins.