Stories For My Mother

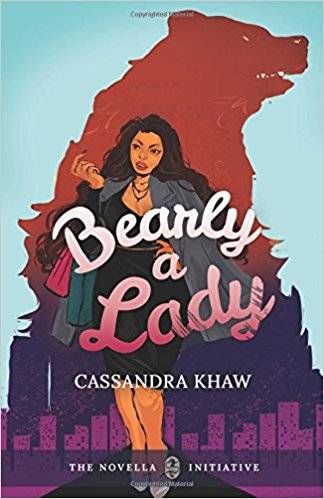

This is a guest post fromCassandra Khaw. Cassandra has written, written about, and been written about in a myriad of press releases. She does social media for Route 59 Games, freelances as a tech and video games journalist, and spends whatever time she has left writing fiction. Bearly a Lady is her first foray into romance, comedy, and people-not-dying-horribly. She can found on Twitter at @casskhaw.

Every story I’ve ever written has been, in one way or another, for my mother.

But I have never written –okay, maybe once– about her.

I’ve wondered why that might be the case. In part, I suspect it was a concern about privacy, a desire to avoid commoditizing what amounts to generational trauma. Which is not to say I’ve not shared some of the adjacent anecdotes. But the actual story of my mother, that one I’ve kept as metaphor, as myth, its narrative steeped in speculative elements. These days, however, I no longer feel the urge to only discuss my mother in the abstract, and I suspect I know why.

My mother’s finally happy.

Or at least, as close to happy as I’ve ever seen her. She works three days out of seven in a business that she spent a decade building. She has her own house, her own car, a community that respects her, a man in her life who happily accommodates her curiosity about new eateries. My mother, while sometimes worried about the softness of her figure, can make it through most of a Crossfit class, which at sixty-four is an impressive feat.

There are ways to make her life better still –her two itinerant daughters could spend more time at home, less time working– but by and large, she has the life she fought for, the life she’d craved. And now that I know the shape of the denouement, I can talk about the beginning.

Anyway.

I write stories for every version of my mother that ever existed.

The six-year-old who watched as her brother gulped down live mice. The eight-year-old who rode for hours on the back of her brother’s bicycle, who knew how to use a knife before she learned to speak a breath of English. The ten-year-old wunderkind who aced every class before her school would present her with a cornucopia of stationery, stationery that she’d then redistribute among her siblings, because they were too poor to afford their own. The fourteen-year-old who inadvisably fell in love with the English tutor who should have known better than to take up with a child.

For them, I wrote cautionary tales, warnings against wolves and those who might abandon a child among the wolves, uneasy fables where there is no division between monster and girl, and the lies that society tell. Nothing wrong about being a monster, child. The error is with your captors.

At eighteen, my mother was told to marry my father. “Don’t bring any more shame to the family,” her mother said, frowning faintly. Three days before her wedding, a woman called to tell my mother to leave. “He doesn’t love you. He loves me,” she said. My mother, trembling, told her husband-to-be that he had three years. Three years to walk away from this other woman, three years to learn to love her, three years to make it right. He didn’t, but that’s another story. At eighteen, alone and afraid, she found the courage to say words that some people spend lifetimes learning to say.

That incarnation of my mother lives in so many of my stories. She is the interstellar diver who braves the darkness to save a ship full of lost loves; she is the carnivorous mermaid who tolerates a prince’s predations, who waits and bides her time until she is ready; she is the woman who walks each year to a hungry highway, who bargains with ghosts to protect people who’d never know her name. She is the nameless daughter of the Dragon King, the goddess Demeter, the fox-wife who learned to be free, all without the skin that her husband had burned, the vengeful ones in a thousand plots, the ones who wait, the ones who hunger, who endure.

I always give her teeth.

When I was younger, I used to wonder at the idea of escapism, what pleasure people derived from worlds not couched in the cold truth. Where is the enjoyment in a fantastical situation that does not exist? How can one exult in a happily-ever-after with a man too good to be real? Better stories that warn against the cruelty that one might face. Better stories that brood over the hopelessness of our circumstances, the apocalyptic events of our present.

Since then, I’ve learned. There is a power in optimism that is so grossly overrated. For all that we might turn up our noses at those who have faith in a better world, we need these narratives.

Especially now.

More than ever, we need stories that tell us that there is hope, there is joy, and who cares if these delights are caricature, there is no shame in dreaming. Bearly a Lady is largely whimsy, spun for the woman that my mother never had opportunity to be. It is grounded in some difficult ideas, but overall, it is a book about true love and female friendships and finding your way in a world that doesn’t quite know how to love you. It is my mother’s romantic dreams, parcelled into a slim little volume. It is my hope that readers will find a place in those pages to pause, to breathe, to smile.