Did Logan Take Its Plot from this Book?

This is a guest post from Clayton Andres. Clayton has written and edited for newspapers, magazines, and online publications across Canada after completing a BA in English and a year of a masters in journalism.

When I saw the latest X-Men movie Logan last month, something seemed awfully familiar about the story.

So, in the movie (spoiler warning), Logan/Wolverine/James Howlett/It’s Basically Just Hugh Jackman, Just Call Him That is working as a skuzzy limo-driver in the near future where resources are scarce, everyone’s poor, and borders are fiercely protected (I know, it’s a pretty big stretch. These films are so hard to suspend your disbelief for, honestly).

Eventually, he runs into a nurse who works at a biological research centre who wants to pay him to escort her and her daughter up North to a mysterious location called “Eden.” Huge Jacked-Man, in typical “I’m a grumpy guy with knives in my knuckles” fashion, refuses, only to later find the nurse has been killed and her daughter isn’t really her daughter at all, but a young Latinx orphan that’s been held by the government in a secret research facility where the U.S. government has been testing and torturing her and other children (again, the government is secretly torturing people? Geez, how out-there can you get?).

Right about this point in the movie I nearly stood up in my seat and yelled, “Wait a minute, I just read this!”

The four narratives converge towards an “Inkatorium,” which is supposed to be a research facility, but is actually a government-sponsored internment camp where “inks,” particularly Latinx families and children, are held, tested, tortured, and sterilized without consent. Oh, and I forgot to mention there’s also a sub-plot involving a gang of skuzzy limo-drivers.

Although the focus of Logan is largely on the road-trip Huge Ackman, Prof. X and the X-23—the young girl who was rescued from the government facility by the nurse—take trying to find “Eden,” the set-up for the plot was so similar I initially assumed they had to have bought the rights to Vourvoulias’ story. Unfortunately, that doesn’t seem to be the case (unless the Internet is lying to me again).

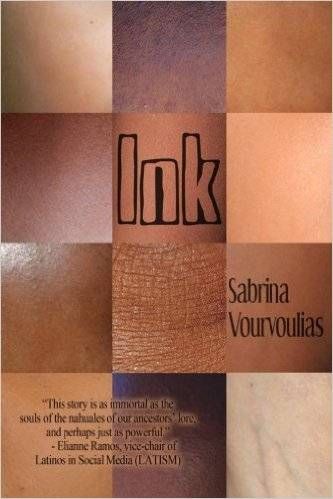

Now, I’m honestly not here to make any accusations. I hope it is a coincidence, and it may well be, since government internment of non-legal citizens in the U.S. isn’t anything new, so it wouldn’t be surprising that an author and a Hollywood screenwriter would both write a dystopian version of this reality. But the fact that Ink, published in 2012, and this year’s Logan both devote sizeable chunks of their respective narratives to fictional facilities where government workers experiment and dehumanize non-white individuals, particularly those of Latin-American descent, I think shows there are artists out there who believe we aren’t living too far from this becoming a reality some day.

I don’t have to remind you of last year’s American presidential election and how much of the rhetoric was focused on detaining, removing, and preventing the movement of non-citizens. And I certainly don’t have to go into how the current government has been attempting for several months to turn that rhetoric into legislation. But I think what Ink, and to a lesser extent, Logan, are emphasizing is how easily those of us in privileged positions can ignore the plights of those subject to the whims of racist government action.

One of the main focuses in Ink is how two-thirds of the main characters are too privileged (namely, they’re white and mostly male) to notice what’s happening right under their noses. The fourth character, a Latinx woman is beaten, raped, and left for dead by a roving band of mercenaries given carte blanche to do whatever they want to whomever the government has given full legal (read: human) status to. It’s only as the privileged characters begin to reach out to their neighbors that they begin to see just how bad the rest of the country has it compared to them.

The same can almost be applied to Logan, even though this section only takes up a small part of the film. Hue Jack-Man has the privilege to refuse to help X-23 because he figures if he keeps his head down, he won’t have any additional trouble in his life. But it’s only when the nurse dies and leaves him a cell-phone video detailing the full extent of brutality X-23 endured that he realizes he’s the only one who can help her.

The X-Men movies are all about mutants fighting against the world’s prejudice against them, and as a result, each film (except for maybe Deadpool) can easily be turned into an allegory for any group of people subjugated because of their race, gender, orientation, or beliefs. But I don’t think it was a mistake to make X-23 and most of her fellow inmates Latinx. Since the first part of the movie takes place in and around the Mexican border, her status as not just a suppressed child, but as a Latinx child who is deemed less-than-human by the U.S. government underlines the harsh realities happening outside the film.

If you loved the movie Logan, I highly recommend you read Ink, which not only expands on the themes of political control and subjugation, but is equally if not much more brutal than the R-rated movie (although yes, there are far fewer knife knuckles). If you haven’t seen it, I’d recommend Ink regardless. It’s not only a story that has become even more potent since it was published half a decade ago, but it’s beautifully written with rich, compelling characters and a whole lot of twists and turns I thankfully haven’t spoiled here.