Everyone’s Into Something: My Field Guide Fetish

My grandfather was in to trees. Field Guides to the Trees of Maryland and Beyond, Poplars and More, Mid-Atlantic Native Shrubs made up a majority of the book shelves. Next came Shakespeare, and then mysteries. Poirot. The race track jockeys of Dick Francis. But those were secondary to the trees.

He especially was in to oaks. When I was born, to celebrate, he planted a dozen white oaks along the crushed oyster-shell lane to the boathouse at his farm on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. First it was cows, then corn and soybeans. Then it was sold to lawyers.

The learning: everyone is in to something. My field guide fetish started probably at age eight, with Volumes One and Two of The Guide to North American Shrubs. Field guides are picture books for adults. I felt very grown-up reading them, and trying to key leaves.

Wild nature, red in tooth and claw, where I found a box turtle, a deer’s skull, got poison ivy, and fished for blue crabs, could be bound. Into a 200 page paperback, with what they called helpful Descriptions, Remarks, and Full Color Plates. It was so comforting.

The stinging itching welt I got swimming in the river at the farm was not from a jellyfish, but from a Sea Nettle, page 90, Plate 31, Chrysaora quinquecirrha. It somehow stung less to know that its “tentacles emerge from marginal clefts,” and “that the marine form is larger.”

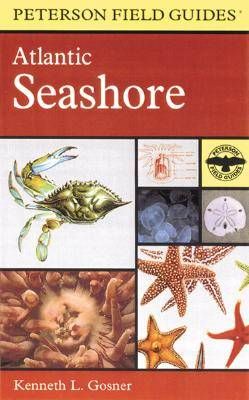

I have ever since been a devotee of Peterson’s Field Guide to The Atlantic Seashore. When I was in my 20s I wanted to be a marine biologist. I studied in the field on an island off the coast of Maine and, along with a stick for thwaking seagulls (they could be very aggressive during nesting season, like Hitchcockianly agressive) I carried my Peterson’s Field Guide. Tidepools became ephemeral little worlds that I entered, and I had words for them, like a lapidist has for jewels.