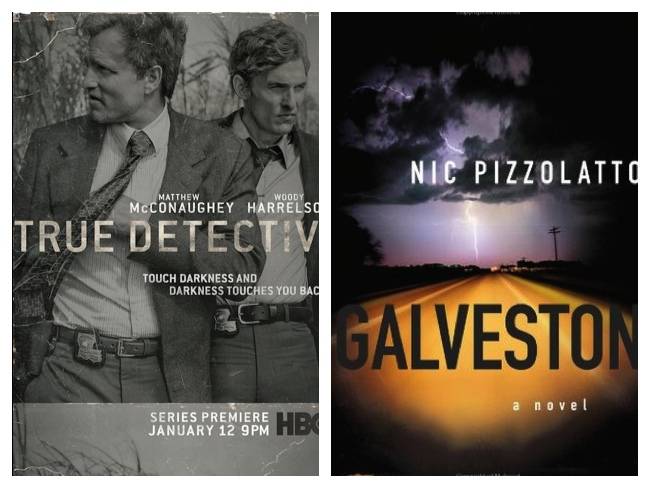

Read and Watch: GALVESTON and True Detective

This is a guest post from M.M. Owen, a British author who has published works of fiction and non-fiction in a range of magazines and anthologies. He is currently studying for a PhD at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. Follow him on Twitter @matt0wen

_________________________

Matthew McConaughey’s portrayal of Rustin “Rust” Cohle in HBO’s True Detective has garnered almost universal acclaim. And with good reason: it’s a brilliant performance. What readers of Book Riot might be interested to know, though, is that there exists a sort of embryonic Rust, amidst the pages of Galveston – a 2010 novel by True Detective‘s creator, Nic Pizollato. Galveston’s protagonist, Roy Cady, is in the business of committing crimes, not solving them. But in almost every other sense, he reads like Rust’s estranged twin, or moral double.

For one, similarities in appearance and circumstance abound. Roy Cady (initials: R.C.) is originally from Texas, but is now working in Louisiana. He takes a scathing view of humdrum human concerns, is haunted by the loss of his wife, and is fond of total solitude. Cady has grown weary of sex, but drinks constantly, cracking bottles of Jameson at midnight “because I didn’t sleep anymore unless I had a load on.” For the keen True Detective fan, there are some even more geekishly exciting moments: “An army of empty High Life cans covered the floor around the chair – an actual army, because I’d used a knife to cut little strips out of the can sides so that the folded down, like arms, and I’d pulled the tops upright to resemble heads.”

Where it gets more interesting, though is in the character parallels. Roy Cady’s philosophy isn’t quite as developed (or at least as articulated) as Rust’s mashup of pessimist philosophers – but the seeds of the latter’s future monologues are there. Cady is told by his estranged ex-wife that “the past isn’t real,” and, despite being initially baffled, he later repeats it to Rocky, Galveston’s only other major character: “It’s just one of those ideas you get that you think is real. It doesn’t exist, baby.” (Not quite “time is a flat circle,” but getting there.) Like True Detective, Galveston delights in toying with the slipperiness of memory, of imagined (often idealised) pasts – and Cady, like Rust, takes an unorthodox view of things: “The lesson of history, I think, is that until you die, you’re basically inauthentic.”

Via its protagonist, what Galveston teases out is one of the abiding themes of True Detective: the past is simultaneously an illusion and a millstone around our necks. It constructs a not-dissimilar paradox around morality, and where the reader really begins to spot the future Rust is in Cady’s inability to live by his own lone-wolf code; the constant evidence that the nihilist doth protest too much. It’s hard to talk about the novel without throwing out spoilers, but where Galveson most significantly predicts True Detective is in its presentation of a world which fails, despite the best attempts of its inhabits, at being irremediably bleak.

In this reader’s humble opinion, Galveston is not a great novel, nor Roy Cady a great character. It’s a solid piece of noir fiction, with occasional flashes of depth, which is most engaging when foreshadowing, in lyrical prose, True Detective‘s love affair with the landscape of the Deep South: “broken cypress trees that passed like brown bones reaching out the mud”; “the hot wind stirring the palms and coursing out to the heavenriver of stars.”

In a sense, though, it is Galveston‘s raw plot, and relatively underdeveloped themes, which Book Riot readers will find interesting. It’s fascinating to see what can happen to a set of idea when they are allowed to germinate (and strengthen) over a period of two years – not least as a way of tracking Nic Pizzolatto’s odd artistic journey. Reports suggest that Galveston is headed for the big screen. This is great news – the novel is a screenplay waiting to happen – but it will intriguing to see how the creators handle it, after True Detective. Assuming they don’t simply focus on Galveston’s noir aesthetic, and downplay the source text’s more philosophical aspirations, probably their biggest challenge of all will be to present a character who doesn’t come off as simply a poor man’s Rust.