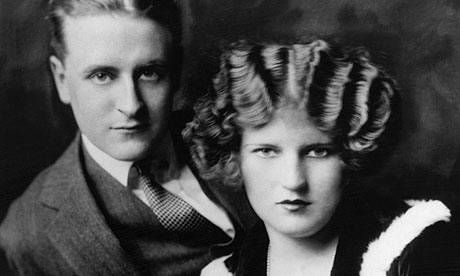

Zelda and Scott’s Creative Communion

This is a guest post from Erika Robuck. She is the author of the forthcoming novels Hemingway’s Girl and Call Me Zelda, is a guest blogger at Writer Unboxed, and is a member of the Historical Novel Society and The Hemingway Society. She tweets at @ErikaRobuck.

_________________________

In the early days of their courtship, Zelda had many suitors’ photos and pressed flower corsages staining her diaries and scrapbooks, in addition to Scott’s, which she willingly and deviously shared with him. Her writings did more than merely fire his creativity; they fueled his jealousy, inspired characters, and even found their way as excerpts into his published fiction.

In THE GREAT GATSBY, Scott must have allowed himself to imagine what would have happened if Zelda had settled on that big football player of privileged family who had courted her in the early days. What if Scott had been left without her, chasing the mythic woman he’d created in his mind, only to find that his creation did not match reality or came at too great a cost? Was Scott’s commentary that Zelda wouldn’t have become the woman he loved so dearly without him, or more sinisterly, that she never was that woman to begin with?

Whatever his meaning, conscious or unconscious, Zelda (or one of Scott’s views of Zelda) haunts the pages of THE GREAT GATSBY. Her words, her actions, and even the quality of her voice inform much of Daisy. Zelda conjured the title of the novel, and graces the opening pages in the dedication. She was also Scott’s first reader, and he often could not continue writing without her impressions. She was his greatest supporter, his sharpest critic, and his muse in the truest sense. They worked in a kind of holy, or unholy, communion.

Zelda performed for Scott from the first night they’d met in an Alabama country club, to the early days of fountain-hopping through the jazz-soaked streets of New York City, to the rich terrain of their friendships and dalliances in Europe, where Zelda’s hold on sanity began to slip. Scott was never far away scribbling her antics, theories, and prophesies on crumpled cocktail napkins. Her role as muse and parasite has long been debated, but if all labels are stripped away, all friendships, indiscretions, alcohol and pills are swept aside, and a single spotlight is left on the man and woman at the center of all of the drama, one can’t help but feel that two artists in pursuit of the same dream—like that green lantern on the end of the dock—are what could have remained. If only.

* * *

For more on the fascinating life of Zelda Fitzgerald, I highly recommend Nancy Milford’s ZELDA, Sally Cline’s ZELDA FITZGERALD: HER VOICE IN PARADISE, and THE ROMANTIC EGOISTS: A PICTORIAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY FROM THE SCRAPBOOKS AND ALBUMS OF F. SCOTT AND ZELDA FITZGERALD.