4 Exceptional Queer Poets for Your Pride Reading

For centuries, beginning with the great Greek poet Sappho, poetry has been among the artistic expressions of the LGBTQ+ community. With just a turn of the phrase or a certain word, the poet has the capacity to reach untapped emotions and revelations. Poetry has expressed the emotional and political spectrum of identity, love, sex, passion, and the injustice of the LGBTQ+ experience. The astounding work of queer poets has helped readers to see and empathize with this community. It has also been the conduit for readers to celebrate and acknowledge their own pride.

How to Love a Country by Richard Blanco

How to Love a Country by Richard Blanco

While Richard Blanco was the fifth Inaugural Poet selected in 2012 to read at President Obama’s second inauguration, he was the first gay poet, the first immigrant and the first Latino poet to be selected for the honor.

Blanco’s poem for the occasion, One Today, is a now classic work that is a nearly pastoral and an optimistic rendering of the country, meant as a balm for what ails its people.

Blanco had a distinctive journey to the United States. His mother was seven months pregnant when she left Cuba for Madrid. The family stayed in Madrid for 45 days, then landed in New York, but soon thereafter moved to Miami where Blanco grew up.

The search for home and for cultural identity as a Cuban American immigrant dominated Blanco’s first book of poetry, City of 100 Fires. Blanco’s following poetry collections, Directions to the Beach of the Dead and Looking for the Gulf Motel, further explores these complex negotiations of how a gay Latino poet finds his way through a culture unwilling to recognize him.

Richard Blanco lives in Bethel, Maine with his husband. If you are ever presented with the opportunity to hear Richard Blanco read his work, please go. The experience of hearing Blanco’s calm and expressive voice embrace and envelope you into his poetry is the sublime poetic experience.

The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde

The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde

Audre Lorde was born in New York City in 1934 to immigrant parents from Grenada. She attended Catholic schools in Manhattan and then studied at Hunter College where she earned her BA. Next for Lorde was receiving a Masters degree in Library Science from Columbia University. Then came poetry.

Lorde’s first volume of poetry, The First Cities, was published in 1968—the same year she met her long-term partner, Frances Clayton. It was not until 1974, after writing poetry on the transience of love, that she published her first book of political poetry, New York Head Shot and Museum.

On the issue of art as social protest, Lorde wrote, “…the question of social protest and art is inseparable for me. Art for art’s sake doesn’t really exist for me. What I saw was wrong, and I had to speak up. I loved poetry and I loved words. If I cannot air this pain and alter it, I will surely die of it.”

In the early 1970s, Lorde was at the forefront of a new feminism representative of women of all colors and sexual orientation—rejecting the white middle class hegemony that had dominated the feminist movement and had excluded lesbians. Lorde was one of the first women who wrote of the intersection of racism, sexism, and homophobia stemming from the culture’s inability to tolerate differences.

Lorde died of breast cancer in 1992. She was the poet laureate for New York City the previous year. In 1997, the definitive collection of her work, The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde was published.

Selected Poems by Frank O’Hara

Selected Poems by Frank O’Hara

Frank O’Hara was born March 27, 1926, in Maryland and grew up in Massachusetts. After studying piano at the New England Conservatory in Boston from 1941 to 1944, O’Hara served as a sonar man in the South Pacific and Japan on the USS Nicholas during World War II.

After the war, O’Hara returned to Harvard, continued with his music studies and working on his compositions, but then met poet John Ashberry and began writing poems for the Harvard Advocate. After changing his course studies to English, O’Hara graduated from Harvard in 1950, received his MA in English studies from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor the next year, and then came came to New York, began work at the front desk of the Museum of Modern Art, and never left the city.

O’Hara’s contemporaries (and friends) of the New York School included the painters Jackson Pollock, Larry Rivers, and Jasper Johns. O’Hara attempted to produce with words the similar effects artists had on canvas. O’Hara’s poetry is sometimes surrealist, sometimes provocative with impromptu lyrics, journalistic phrases and witty observations—but O’Hara is always brilliant.

Very sadly, O’Hara died in a sand buggy accident while vacationing in Fire Island when he was a very young 40 years old.

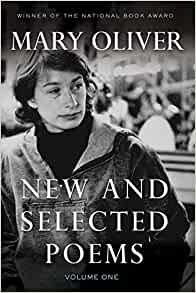

New and Selected Poems by Mary Oliver

New and Selected Poems by Mary Oliver

Mary Oliver attained a rare and iconic status: the well-known and best-selling poet who published a poetry collection every other year. Oliver did not come from any elite academic institution and never went to college. She was considered “an older poet,” a poet who perceived their poetry to be a direct communication with the reader—and therefore the need for any personal detail regarding the poet’s life was a distraction.

Oliver grew up in Ohio with a sexually abusive father and a neglectful mother. From the age of 14, Oliver found her greatest solace and wisdom in nature and would write in a small notebook as she hiked. It is easy to see the similarities with Oliver and Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau; their emphasis was on the natural world above all else. “To pay attention, this is our endless and proper work,” Oliver wrote about her poetry.

Oliver’s poetry is very accessible: she writes in a common and plain style of love and prayer and beauty in an almost pastoral style reminiscent of Edna St. Vincent Millay, Elizabeth Bishop, and Marianne Moore. Oliver’s vision was of learning to love the world despite the world’s brutality and pain.

Oliver and her partner, Molly Malone Cook, lived in Provincetown, Massachusetts, for 50 years. Oliver died in 2019 of lymphoma. The following lines from “Wild Geese” exemplify this vision of Oliver’s: to show up and pay attention.

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert, repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile the world goes on.

The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde

The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde Selected Poems

Selected Poems