Let’s Talk About Slavery

The true impact of American chattel slavery is one of the most divisive racial issues of our day. Many Americans just don’t think that hundreds of years of enslavement and subsequent social, political, and economic degradation as rule of law was that big of a deal, and that the descendants of African slaves are wholly responsible for their unique position in the fabric of American society. American schools and educational systems, never quite thorough enough in their depictions of American slavery to begin with, reinforce these views, which eventually lead to the muddling of many conversations on the effects–and repair–of racism. It seems that, when it comes to facing the realities of American slavery, many people would rather pretend that things were a lot less horrible than they actually were.

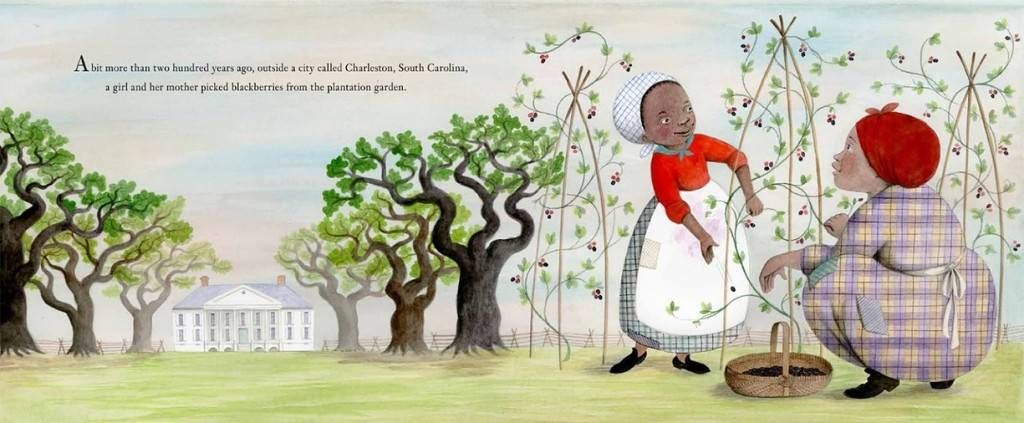

A Birthday Cake for George Washington is a children’s book that tells the story of slave chef Hercules, his daughter Delia, and their happy quest to make a cake for the first president of the United States of America. Criticism of the book came quickly, especially considering that this was released a few months after A Fine Dessert, another children’s book that depicts chattel slavery as bascially a pretty chill time as long as your boss wasn’t a jerk. The team behind A Birthday Cake for George Washington, unlike the folks behind A Fine Desert, was a diverse group of people. The editor, Andrea Davis Pinkney, is black and is a recipient of the Coretta Scott King Award. Naturally, the book and its subject matter has been defended by the creative team, but that didn’t stop Scholastic from pulling it off the shelves.

Aside from my deep confusion at the fact that a book like this was published after the metric ton of criticism that surrounded A Fine Dessert, I find myself wondering exactly why the creative team thought that this happy-go-lucky depiction of slaves was an acceptable thing to do. A tirade on what children should and shouldn’t be exposed to isn’t something that I feel comfortable doing–I’m not a parent, and I generally steer clear of children anyway because they have cooties. But this depiction of slaves and slavery seems very disingenuous. Slaves themselves have repeatedly given us an inside view on the particular systemic and individual horrors that they faced during their time in bondage through a particular literary form: the Slave Narrative.

This is not to say that there should be depictions of lynching and other kinds of horrible violence that slaves endured in children’s literature. Far from it. But a simple review of slave narratives (there are over 200 of them at DocSouth, and online archive curated by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) shows that slavery was not a particularly happy time for those in servitude, even if they were performing a sort of happiness at their tasks in order to lessen the impact of their “unspoken, bittersweet reality.”

Here’s an excerpt from Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, where she discusses how she had to hide in a dark, enclosed space for seven years in order to escape from the sexual attentions of her master:

I hardly expect that the reader will credit me, when I affirm that I lived in that little dismal hole, almost deprived of light and air, and with no space to move my limbs, for nearly seven years. But it is a fact; and to me a sad one, even now; for my body still suffers from the effects of that long imprisonment, to say nothing of my soul. Members of my family, now living in New York and Boston, can testify to the truth of what I say.

Countless were the nights that I sat late at the little loophole scarcely large enough to give me a glimpse of one twinkling star. There, I heard the patrols and slave-hunters conferring together about the capture of runaways, well knowing how rejoiced they would be to catch me.

Season after season, year after year, I peeped at my children’s faces, and heard their sweet voices, with a heart yearning all the while to say, “Your mother is here.” Sometimes it appeared to me as if ages had rolled away since I entered upon that gloomy, monotonous existence. At times, I was stupefied and listless; at other times I became very impatient to know when these dark years would end, and I should again be allowed to feel the sunshine, and breathe the pure air.

Here’s Solomon Northup, of 12 Years a Slave fame, on whippings:

It was rarely that a day passed by without one or more whippings. This occurred at the time the cotton was weighed. The delinquent, whose weight had fallen short, was taken out, stripped, made to lie upon the ground, face downwards, when he received a punishment proportioned to his offence. It is the literal, unvarnished truth, that the crack of the lash, and the shrieking of the slaves, can be heard from dark till bed time, on Epps’ plantation, any day almost during the entire period of the cotton-picking season.

The number of lashes is graduated according to the nature of the case. Twenty-five are deemed a mere brush, inflicted, for instance, when a dry leaf or piece of boll is found in the cotton, or when a branch is broken in the field; fifty is the ordinary penalty following all delinquencies of the next higher grade; one hundred is called severe: it is the punishment inflicted for the serious offence of standing idle in the field; from one hundred and fifty to two hundred is bestowed upon him who quarrels with his cabin-mates, and five hundred, well laid on, besides the mangling of the dogs, perhaps, is certain to consign the poor, unpitied runaway to weeks of pain and agony.

In A Birthday Cake for George Washington, Delia and Hercules have to perform a very specific task for the man who owns them body and soul, when they discover that an ingredient crucial to their success is missing. They locate a substitute, complete the task, and everything goes over well. But considering the reality of slavery, where the presence of an errant dry leaf in a day’s picking of cotton warrants 25 lashes of the whip, it’s entirely possible that Hercules could have been sentenced to a “mere brush” if Washington took offense to their substitution. That reality is not something to dismiss or depict inaccurately.

If the words from the mouths of slaves are to be believed, days on the plantation held very few things for them to smile about.