Reader, It Blew My Mind: The Legacy of Jane Eyre

One of the most impactful literature classes I took in college was a simple, 100-level class: “British Literature: 1850–Present.” Anglophile book nerds have all probably taken this class, along with its less popular sibling, “British Literature: 1000–1850.” I didn’t expect the class to be important in my learning curve; I expected to waltz in, read (most of) most of the books, dazzle the professor with my ability to write an A-grade paper in a day (a superpower that is utterly useless in the world outside academia, more’s the pity), and waltz out again.

But the professor, a newly-minted PhD in her first official position, had other ideas than the usual Dickens to Wilde and on through the drawing room dramas of British literature.

Instead, she decided to teach us a visceral lesson on the legacy of Jane Eyre by choosing works that are based — directly or loosely — on Brontë’s seminal tale. We spent the entire semester looping book after book back to Jane, to the madwoman in the attic and physical manifestations of inner turmoil, to disapproving aunts and dead best friends. I’ve been thinking about that class for almost 20 years, and have used it as a jumping-off point for many animated discussions about how all art is intertwined, and if you look at it from a certain angle, everything is art.

To borrow a phrase: Reader, it blew my mind.

What is it about Miss Eyre that keeps us coming back to her story? Personally, I will never pass up a strong female character, and Jane’s particular brand of iron-clad will is immensely satisfying. Everyone underestimates her at every turn, and yet she simply continues forward, doing what she believes is right and necessary. She believes in herself, wholly and without reservation. While there are valid arguments to be made that Jane Eyre’s fate is a somewhat dismal one — caring for a (wealthy) blind man and being a social outcast for the rest of her days — it is her choice to do so that ends the tale. She marries him, and not the other way around. The continual retellings and re-framings of Jane’s story — as well as the stories of the characters around her — prove to me that we will never have enough stories of determined young women in this world.

And so today I am going to discuss the high points of the syllabus of that surprisingly fateful class, along with a couple of newer retellings to round out the list. Consider this a companion piece to this awesome roundup of Jane Eyre retellings wherein I dig in a little further into the “why.”

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë (1847)

As the King of Hearts said, “start at the beginning.” Jane Eyre is the story of an orphan girl in England, sometime late in the reign of George III (d. 1820). It is a five-act story: her abusive childhood at Gateshead Hall, her education at Lowood School, her position as a governess at Thornfield Hall, her escape to Moor House, and her eventual return to Thornfield Hall, culminating in a reunion and marriage to Mr. Rochester, her former employer. It is a first person narrative, and one of the first novels to feature a female protagonist making her own moral decisions as opposed to the ones that society or the men around her dictated.

As with any challenge to the cultural expectation of women being submissive to the men in their lives, Jane Eyre was received with no small amount of outrage. It was called “un-Christian” and “lacking moral value.” My readers will not be surprised to learn that it was also an instant best seller.

Interestingly, while film versions of Jane Eyre are usually set closer to the publication date, today I was reminded that the actual timeframe of events is 1808–1820, based on references in the text.

Rebecca by Daphne Du Maurier (1939)

My adoration for Du Maurier’s Rebecca increased threefold when we studied the correlations between it and Jane Eyre. Du Maurier takes Brontë’s first person narrative one step further in never naming her narrator, and both women share a history of being abused and neglected orphans. The utterly creepy Mrs. Danvers steps in as Bertha Rochester, channeling a whole different flavor of madwoman in the attic, while Maxim de Winter’s refusal to discuss his former wife with his new bride echoes Rochester’s refusal to tell Jane about his actual wife in the attic (aghhh). The men in both stories are obviously incredibly flawed, and the protagonists not only recognize those flaws but also voice them and demand better in the future. Both stories culminate in a fire, cleansing the couples of the past and allowing them to move forward with their lives together.

Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys (1966)

Wide Sargasso Sea is a deliberate prequel to Jane Eyre from the point of view of Antoinette Cosway, Edward Rochester’s first wife, whose madness forms the basis of the tension in Jane Eyre. Antoinette has a foot in two worlds, as a Creole, Jamaican-born Englishwoman. The setting of WSS has been moved from late Regency to shortly after the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833.

The story follows her through Rochester’s gaslighting and the shredding of their marriage, with Jane herself never named and only a shadowy fringe character; this is because Rhys understood that Rochester’s sins do not stain another woman, nor is Jane’s ignorance of Antoinette’s existence her (Jane’s) fault. WSS deals heavily with postcolonialism in the United Kingdom, as well as issues of slavery and ethnicity. It is written in a gorgeous, lush, lyrical first person style, at times shifting between Antoinette and Edward as their relationship crumbles. Wide Sargasso Sea requires us to question the relative truth of Jane’s narrative in the original text, as well as Rochester himself as seen through Jane’s eyes.

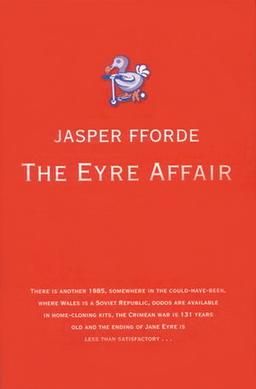

The Eyre Affair by Jasper Fforde (2001)

The Eyre Affair is a delightful surrealist romp through a parallel England in which books are an integral part of the fabrics of time, space, and yes: reality itself. In Thursday Next’s England, Jane Eyre agrees to marry her cousin St. John, moves to India to be a missionary, and lives a content but melancholy life.

People who have read Jane Eyre in this timeline have always found the ending rather dull and disappointing. Hijinks ensue, the outcome of which is that Thursday takes a job as a LiteraTec, tasked with keeping characters inside literary works in line. It is a romp and deeply, deeply strange, but it is a testament to the enduring legacy of Jane Eyre that an entire series of novels began with a twist on her story.

Re Jane by Patricia Park (2015)

The challenge of moving Jane Eyre’s journey into the modern day is that we like to think we have largely rejected many of the overt expectations that guided Victorian life. Park moves Jane into a modern culture with strict codes of behavior in order to draw a parallel. Jane Re is a Korean American orphan whose story loosely retells that of the original Jane. Traveling from Queens to Korea and back, this Jane’s story is less about the strictures and expectations of Victorian society and more about the expectations placed upon immigrants, especially those of Asian descent, by the combination of the cultures they represent. It’s more about finding oneself than staying true, although as ever those two concepts are so enmeshed as to be nearly indistinguishable.

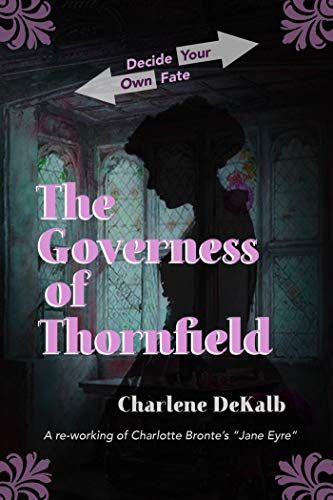

The Governess of Thornfield by Charlene Dekalb (2020)

First person narratives are all well and good. They allow us to sink into the mind of the narrator, to experience their story through a narrower lens, much like we might if we ourselves were experiencing the story. DeKalb takes that one step further and merges Jane’s experiences with a decide-your-own-fate trope. This combines the reader and the narrator in ways that Brontë, certainly, would never have expected. How will you achieve your own happily ever after? Is it even possible? Would a modern person be able to navigate the pitfalls and mores of Victorian society? I confess that I haven’t yet read this one, but I’m very interested to explore it.