Just How Absurd is Yayoi Kusama?

This month, my Instagram and I had the awesome opportunity of seeing the “Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors” exhibit at the Seattle Art Museum. The main feature of the show is you! Kind of. Mirrors plastered in rooms display endless reflections of hanging lanterns, fields of pumpkins, and whoever else happens to be inside. The result is a transportation to a beautiful, otherworldly dimension- and a great photo. Traveling through posts tagged #kusama or #infinitymirrors, floods of teenagers and young adults capture the spectacle with smug, happy faces.

At the end of the exhibit, I faced a television screen, and I watched Yayoi Kusama describe her hope for younger artists and the bright future they can create.

And suddenly, I knew my fate. I knew before I even saw it in the gift store. I knew before I even knew it existed.

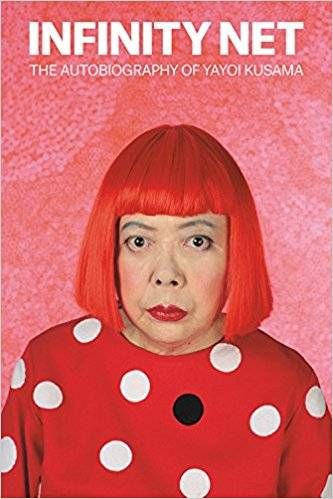

I bought her autobiography.

Repetition. Accumulation. Infinity.

It made me wonder how absurd Kusama truly was.

Not nonsensical, but absurd. The existentialist kind. The kind used in Albert Camus’ essay The Myth of Sisyphus, where he states “[t]he absurd is born… [when] the human need [for reason] and the unreasonable silence of the world” meet. It describes the universe to a person who understands that life is irrational and void of meaning.

Understanding repetition is one of the first signs of absurdity.

In his essay, Camus focuses on Sisyphus, a widely considered villain of Ancient Greek mythology who cheats death. As a punishment from the gods, he is forced to roll a rock to the top of a mountain, watch it fall down, and repeat the process for eternity.

Camus writes, “According to another tradition… he was disposed to practice the profession of highwayman. I see no contradiction in this.”

Existentialism argues that any life a person has- such as the life of a highwayman, for example- is the same as Sisyphus’ punishment. We all are doomed to a routine. We all wake up, eat, drink, work, go to sleep, wake up, eat, work, and so on until we die. The only difference between our lives and the fate of Sisyphus is that Sisyphus doesn’t have hope or purpose. Most other people do.

Sisyphus is forced to accept his torture and his life. For facing the truth of the universe at every waking moment, for understanding the absurdity of the world, and for being devoid of hope, he is declared by Camus as the “absurd hero”.

And although he is suffering, he is “awake”. Camus concludes, “One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

Kusama’s repetitions also gives her the potential to be an “absurd hero”. I think her Infinity Net paintings show this potential best. Before her rise to prominence, Kusama put “virtually every penny [she] had into materials and canvas [and] painted and painted… Over a jet-black surface [she] inscribed to [her] heart’s content a toneless net of tiny white arcs, tens of thousands of them… [She] got up every day before dawn and worked until late at night, stopping only for meals.”

Just like Camus’ interpretation of Sisyphus, Kusama found her work simultaneously joyful and tragic. She “believed that producing the unique art that came from within [herself] was the most important thing [she] could do”, but she was also suffering from “severe neurosis. [She] would cover a canvas with nets, then continue painting them on the table, on the floor, and finally on [her] own body… the nets began to expand to infinity.”

In some ways, Kusama fits all the requirements to be the perfect model of absurdity. She consciously performs the same actions over and over. She states in her book that she rejects religion (which existentialists believe “elude[s]” the truth). She is aware that life is an illusion, as seen by her “Love Forever” room that depicts life as a dream-like “kaleidoscope” of blinking lights.

But Kusama believes in hope, the eternal, and meaning. She strives to bring love and joy to the future where Camus insists that these are pointless delusions. She is fascinated by the “infinite infinities [that] exist beyond our universe” where Camus believes the universe is limited. She firmly puts her faith in being part of a larger whole where Camus insists there is no unity. As distant as she can be from reality at times, she still has a purpose.

“I feel how truly wonderful life is, and I tremble with undying fascination for the world of art, the only place that gives me hope and makes my life worthwhile. No matter how I may suffer for my art, I will have no regrets. This is the way I have lived my life, and it is the way I shall go on living.”

Her exhibit will continue at the Seattle Art Museum until September 10, 2017, where it will then move to The Broad in Los Angeles from October until January 2018. Her own museum in Tokyo is also opening in October. If you get the chance to visit her museum or exhibits, make sure to grab her autobiography Infinity Net on the way out! I’ve only scratched the surface of the infinity that is Yayoi Kusama.