On the Road: Books about Travellers and Roma

With the booming economy in the 1900s, thousands of people left their rural homes and joined the battering ram of urbanization, setting up new homes in the city and commencing a life of work in the concrete jungles. Economies are boom and bust of course, and the bust that came in the 1920s hit the world hard. Books about “gypsies” tell how, as the 1930s pushed onward, people in Europe returned home to their rural hometowns, casting out the settlers who had moved in to undertake the required work to keep those areas going.

Those cast out found themselves nomadic for the first time in generations – among them the Roma people who had lived in Europe for hundreds of years. Though recognised as a nomadic group, the reality is that Roma people were settled in the towns and villages of Europe for many years. And though talk about genocide in World War II focuses mostly on the impact on the Jewish communities in the Holocaust, the Roma too were targeted for destruction. They call it the Porrajmos, or ‘devouring’. Their records are poor because they have never had an opportunity to collect their own history, but estimates suggest that between 500,000 and 1,500,000 Roma died in the Porrajmos, many of them at Birkenau. Though it’s very hard to locate, And the Violins Stopped Playing by Alexander Ramati tells a true tale of a Roma family who faced the horror of the Porajmos.

It’s 2018, and the Italian Prime Minister Matteo Salvini has expressed interest in collating a list of Roma people before expelling them from Italy. It sounds like the same actions undertaken by the Nazi party in order to prepare for their ‘Final Solution’ – but Salvini has merely shrugged this off when confronted with it. He says that expelling these people is an ‘answer to the Roma question.’ That terminology is both familiar and frightening.

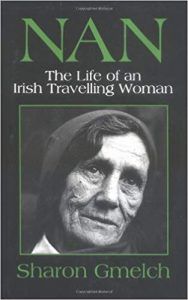

The Roma are not the only nomadic group in Europe – the Irish Travellers, Romany, Lom, Dom, and Sinti are all nomadic or once-nomadic groups, all tarred with the same brush of criminality and condemned to the margins. It is important here to recognise the privilege of not belonging to one of these groups, where poverty is rife, education outcomes are poor, prison representation is too high, and ongoing social issues around violence in the home, LGBTQ rights, and high rates of suicide all have to be considered. Jewish communities after World War II were able to work together to build and commemorate their history. The Roma had no chance to do that, and as a result, their history is pottered and incomplete, carried mostly by the community itself and the few charities who work with these groups.

The universal experience of these nomadic communities is one that isn’t shared by the vast majority of people on this planet and the intersectionalities of these groups with other minorities need better exploration in our books and in our author’s voices. I’ve worked with the Traveller and Roma communities over a period of years but I’m not one of them. What does it mean to be LGBT and a Traveller? How can the world better support mental health concerns of minority groups where shame still plays such a heavy role in daily life? How can we engage groups that have suffered so much, and where can we gain trust? The answer isn’t in Matteo Salvini’s list.