MAD Magazine: A History of The Counterculture Humour Magazine

There were two magazines I read avidly as a teen in the 1990s, MAD and Entertainment Weekly — clearly I was a movie nerd. I still remember laughing along to spoofs of films like Rambo, Forrest Gump, and Star Wars. I didn’t analyze it at the time, but looking back, MAD‘s satirical writing was an incredible tool for learning to question the media we consume.

Did you ever think about MAD magazine as a form of critical literacy? If not, revisit past issues and marvel at some of the clever ways that it criticized politicians and celebrities, mocked advertising, and ridiculed popular films.

E.C. (Educational Comics) was founded by Max C. Gaines in the mid-1940s. They mostly put out educational information and Bible stories. When Gaines died suddenly, the company was taken over by his son, William M. Gaines, who renamed it “Entertainment Comics” and focused on publishing pulp genre comics for young boys as well as horror comics like Tales from the Crypt.

Writer-artist Harvey Kurtzman started writing for E.C. in 1949. Then in 1952, Gaines asked Kurtzman to develop a humour magazine, and MAD was published in comic book form. It began as a ten-cent comic book, parodying other comics as well as newspaper comic strips, films, and other parts of entertainment culture. During that era, however, comics content was policed by the Comics Code Authority.

Comics Code Authority

If you, like me, had never heard of the Comics Code Authority, here is a short detour from the main point of this post. Formed in 1954 to sanitize comics of sex and violence, the program was a reaction to the post-war American paranoia that comics were warping children’s minds. Some things never change, I guess.

In reaction to the bad press, comic publishers banded together to create the Comics Magazine Association of America and they agreed to adopt the code. The original decree read that “The comic-book medium, having come of age on the American cultural scene, must measure up to its responsibilities…To make a positive contribution to contemporary life, the industry must seek new areas for developing sound, wholesome entertainment.” Gaines was against this from the start and tried to fight against submitting his comics for review; unfortunately, wholesalers would only sell code-approved comics.

Eventually, Gaines relented, but not for long. That same year he resigned from the Comics Magazine Association of America and relaunched MAD as a magazine. According to MAD artist Tom Richmond, the code isn’t the actual reason the format changed. Kurtzman, who thought of comics as low-brow, was threatening to walk for a magazine position elsewhere. Magazines were seen as slicker and more respected. The fact that the switch also provided an escape hatch from the code might have been a bonus, though.

It’s a MAD, MAD, MAD World

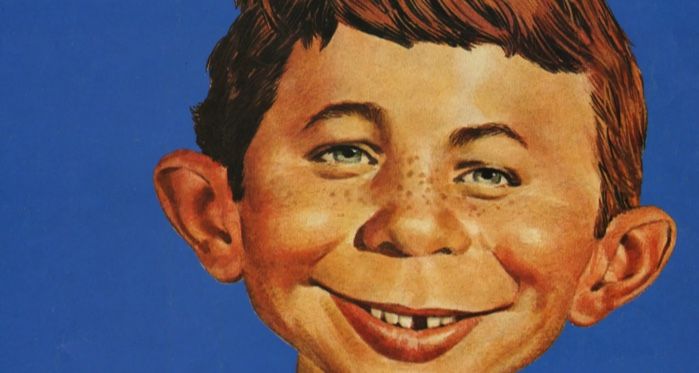

It was then that MAD started to take shape, with numerous recurring features. First, the birth of their iconic spokescartoon, Alfred E. Neuman — immediately recognizable with his red hair, freckles, and ever-derpy expression. The often-repeated story about the character’s creation is that Kurtzman saw a Neuman-esque figure on an illustrated postcard. According to the Smithsonian magazine, the postcard had “Me Worry?” as its message. Kurtzman adapted the figure and the catch phrase, and would paste it into the margins of unrelated stories. It caught on, though, and Neuman became their most consistent cover model. Despite Kurtzman’s part in the figure catching on, the artist behind the most recognizable version of the character is Norman Mingo.

One of my personal favourite features was the back cover Fold-In, a concept created by contributor Al Jaffee. The Fold-In would reveal a hidden image when readers pressed the two sides of the inside back cover together, you can see examples in motion here.

The Influence of MAD

Kurtzman didn’t stay long, moving on in 1956 to a new humour magazine with a bigger budget but no lasting success. The editor-in-chief position went to Al Feldman, who stayed with MAD for 30 years until he retired. It was then helmed for three decades by John Ficarra, the longtime editor who broadened the staff’s diversity and brought the magazine into the online world. He clearly understood MAD at its best, describing MAD’s mission statement as, “Everyone is lying to you, including magazines. Think for yourself. Question authority.”

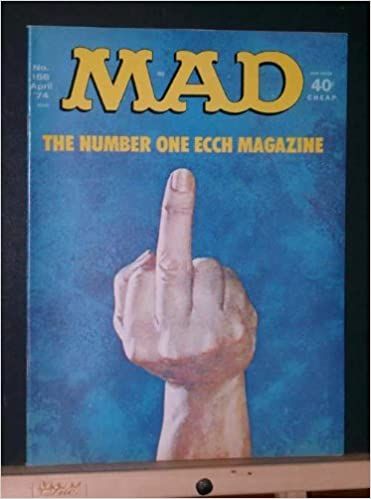

One example of how they reminded readers of that was mock advertisements — Gaines didn’t allow the use of real ads for decades. It is in that spirit of trickery that MAD thrived. In April 1974, the cover image was of a big ol’ middle finger. Many newsagents wouldn’t stock the issue and Gaines had to issue a public apology. Nevertheless, many would come to view the magazine as a willing participant in the counterculture movement.

The magazine has inspired many comedians and comic book artists, with famous fans like Roger Ebert, Robert Crumb, Michael J. Fox, and Weird Al Yankovic. For decades it remained a comedy institution — in 1966, MAD even inspired an Off-Broadway musical show with lyrics by Mary Rodgers and Stephen Sondheim! There was also MAD TV, a sketch comedy show loosely based on the magazine, which premiered on October 14, 1995, and ran for 14 seasons. Its reign over popular culture even led to numerous lawsuits over the years — the magazine battled Irving Berlin and even the FBI at one point.

What, MAD worry?

In the early 1970s, MAD’s readership peaked at more than 2 million. Unfortunately, like most print media, their numbers declined as TV and the internet became mainstream — by the time a magazine issue would be published, readers would have long-since moved on to the next big thing. It was easier and faster for comedy fans to tune in nightly to chat shows and watch monologues about issues that had been in the news that same day. Also, as Ficarra has noted, the world we live in keeps getting wilder and harder to parody. “All these people who grew up reading MAD now have a MAD sensibility, and they’re bringing that to their professions. I guess we’ll all burn in hell for that.” And because these MAD-raised professionals work for brands with immediate access to customers via Twitter and other forms of social media, satire is basically everywhere now.

In the 2000s, the magazine struggled to make new fans while retaining the old ones. The content became crasser and the sense of humour more modern. In another initiative, the staff was diversified through an intern program; at very long last, women became more consistently part of the masthead.

Then, in April 2018, MAD announced it would be a bimonthly release and other changes followed: moving its production from New York to Los Angeles, the magazine announced it had begun anew with a whole new editor-in-chief, logo, and art and editorial departments.

Alas, it wasn’t enough to revitalize the brand and DC, long since having acquired the magazine, decided in 2019 to stop publishing regular issues. New issues are only available at comic book stores and through subscriptions and mostly feature reprints of classic comics and stories.

In the end, MAD gave us gift after gift — not only the witty, cutting work of their talented Gang of Idiots, but all the other artists they inspired with their weird and wacky worldview. And even though they aren’t printing much new content anymore, a 67-year print run is a pretty incredible legacy to leave behind.