The Rise and Fall of the Western

What, exactly, is a western novel? Westerns loom large in the literary imagination, whether the word conjures up images of cowboys and gunslingers, a dusty saloon, or what I like to call the “shirtless adventure men” category of romance novel covers. Unlike other genres where, for example, fantasy elements might make their way into a science fiction story, readers tend to view westerns in more black and white terms. Readers are either devoted consumers of the genre or never see themselves picking up a western book. For many, the hallmarks of the genre, with its focus on themes of adventure, justice, and the mythologizing of American culture, are the reason why they either love it or avoid it. More than any other genre, the lines of what makes a book a western don’t seem to blend as effortlessly into different writing categories. This firmness has led to the idea that westerns are one thing and one story, at least by those not familiar with them. The western is a genre with a long history of stories that hit at the heart of how Americans have envisioned themselves and their relationship to the West and the frontier. From the dime store paperbacks of the 1860s to the modern, LGBTQ+ takes on the genre today, westerns as a genre have come to symbolize a uniquely American take on the art of storytelling.

Like many popular genres, westerns first took off in the mid-1800s during the era of penny dreadfuls, which serialized a book over monthly publications. For readers fascinated with the expanding American west, the novels provided tales of adventure in a new setting, as well as a way to conceptualize a rapidly expanding nation. Many scholars of the genre consider The Virginian by Owen Wister to be the first “official” western novel. Published in 1902, it tells the story of an unnamed narrator who arrives in Wyoming from “back east” and takes a job as a ranch hand. Over time, he becomes a foreman on the ranch, falls in love with the local schoolteacher, and wrestles with the temptation to best his nemesis. These situations and characters, notably the remote Wyoming setting, sparked the imaginations of readers living in the “back east” that Wister described. While Wister’s novel was far from the first take on the frontier adventure story to appear in print, it’s become a classic for its themes of ranch life and the image of a determined yet controlled hero who is ultimately concerned with fairness and behaving like a gentleman. The Virginian put in place what came to define westerns: a lone wolf type hero on the frontier, who must maintain his honor, pursue justice, and ultimately ride off into the sunset.

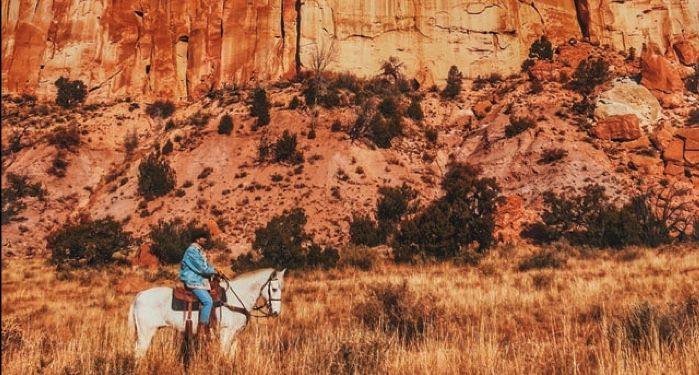

From the early novels of the 19th century, the genre continued to gain popularity, mainly as frontier mythology gained more and more ground in the American imagination. With the westward expansion of the U.S. government, it naturally followed that there would spring up a new form of writing devoted to the stories surrounding this expansion. The west itself plays a crucial role in most westerns, with sweeping vistas and dusty towns that often lead to long spells of loneliness for our hero. The western genre also provided a means of grappling with what westward expansion meant for relationships between settlers and those who already lived in their overtook territories. One common trope of the western novel is a Native American character, who is either portrayed as the wise sage side player to the principal white character or as a nameless savage who symbolizes the wildness of the frontier, in contrast to the civilization that the main character supposedly represents. Similar treatment is given to characters broadly portrayed as Mexican, who are often cast in bandit roles or in some other way that implies they contribute to the lawlessness and violence of the frontier.

After the early years of westward expansion narratives, the western picked up steam with the gangster and train robbery novels of the 1920s. It maintained its popularity throughout most of the 20th century, peaking in the 1960s during the golden age of western books and movies, television shows, and comic books. With the Cold War simmering in the background, Americans were hungry for heroes, whether cowboys or Superman, who exemplified a set of values seen as trumpeting the American cause. Over the next few decades, movies like High Noon, series like The Lone Ranger, and books like True Grit gradually gave way to the new westerns of the 1980s and ’90s. Writers like Louis L’Amour and Corman McCarthy gained traction with books that exemplified the genre and went beyond its traditional confines. For example, McCarthy’s 1992 novel Blood Meridian is known for being one of the first westerns to portray the violence and depravity of western towns through the eyes of a teenage boy living on the U.S.-Mexico border.

The subversion of the American mythology in these novels marked a sea change for both western writers and their audiences, who were increasingly moving beyond the lone wolf hero stories to ones with more morally complex characters. Also driving the changes in the genre was the drop-off in reader interest. After a glut of western media in the 1960s, new genres, such as science fiction, began to take center stage. The popularity of westerns faded continuously through the 1990s and up to the present. Also marking a significant change in the genre was the introduction of “adult westerns,” AKA cowboys (and cowgirls) having sex. While some looked down on this deviation from the traditional form of the novel, the adult market for westerns was one of the few consistently strong areas of growth for the genre in the 21st century.

It would be easy to dismiss westerns as stereotypical stories of westward expansion: classic hero narratives remixed for American audiences curious about adventures on the frontier. But like all genres, there’s a variety of authors and plots under the western umbrella, with writers like Anna North and James Welch redefining what it means to be the main character in a western and the bounds of the genre. Additionally, new splinter genres, like western fantasy and sci-fi western, have arisen, giving readers more options than ever, and events like the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering showcase emerging authors in the field. If you’re ready to take a deep dive into the genre, you can check out Book Riot’s westerns archive or start with the five books rounded up below for an overview of both classics in the genre and new releases that shake things up.

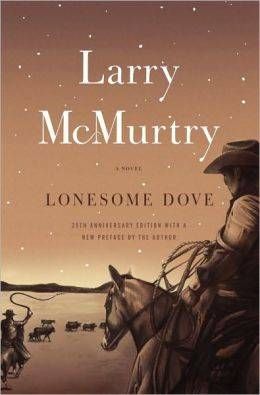

Lonesome Dove by Larry McMurtry

Lonesome Dove is one of the most well-known westerns to come out of the time when the genre was transitioning from the pulp novels of the ’50s and ’60s to the new western era. An epic novel set in rural Texas and on a cattle drive north to Montana, it follows two Texas Rangers going on one last adventure. The setting and characters will give you a sense of the genre as a whole while also showing off McMurtry’s writing style and sense of place.

Fools Crow by James Welch

Written from the perspective of Fools Crow, a young man living in the Two Medicine Territory of Montana, this is a story of what happens when white colonizers move into the territory. This perspective has been left out of traditional westerns, and Welch provides a much-needed injection of perspective into the typical canon.

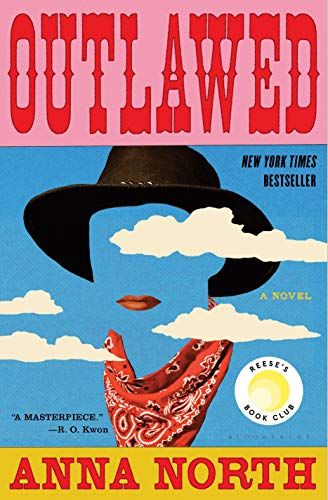

Outlawed by Anna North

A feminist take on the outlaw story. Ada is 17 and thrilled to be married, but when she’s yet to conceive a year later, she becomes an outcast and is threatened with hanging. To survive, Ada must flee her hometown and join up with a group of “outlaw women” lead by their charismatic leader, The Kid. The Kid dreams of creating a haven for women such as Ada, but doing so will put Ada and the other outlaws at risk. This is a heart-pounding, action-packed novel.

Where the Lost Wander by Amy Harmon

If you’re looking to dip into the western romance genre, try this book about romance and loss on the Overland Trail. Naomi May is a young widow determined to find a better life out west. John Lowry is a half-Pawnee young man who feels caught between two worlds. This book offers up the sweeping setting of a classic western alongside swoon-worthy romance and discussions of race and racism in the American west.

Cowboys and East Indians: Stories by Nina McConigley

While this short story collection may not be a genre-style western, its Wyoming setting and focus on stories of opportunity will appeal to fans of the genre. McConigley weaves together the often-overlooked stories of immigrants in the rural west and their connections to the people and land of the western region.

Ultimately, I believe we read both for entertainment and to answer questions about what it means to be human and what connects us. Just as science fiction books might help us figure out our relationship to technology, or horror might help us navigate fear, westerns appeal to readers because they explore key questions about justice, American mythologies, and our relationship to the history of the American west.