Wolves in Sheep’s Clothing: 5 Books to Get You Mad About Fast Fashion

We all know the satisfaction of ducking into H&M or Forever 21 for a quick browse and emerging with the bargain of the century. Hot pink blazer? Barely costs more than a sandwich. Sparkly silver romper I’ll probably never wear? Only $10 on the sale rack. Shopping at big brands isn’t just the least expensive option; it’s often the only one, since most Americans, especially cash-strapped millennials, don’t have the luxury of buying more expensive clothes. By allowing us to dress for life’s new challenges without breaking the bank, it seems like fast fashion is doing us a favor.

But while we’re paying less than ever for our clothes, more and more information is emerging about their true environmental and human cost. Fast fashion contributes to global pollution more than any economic sector except the oil industry—outpacing even international flight. And by concentrating production in countries with the lowest wages and least protective labor laws, big brands facilitate worker exploitation and contribute to the decline of unskilled jobs in countries with higher wages. It can be tricky to understand the insidious practices of global corporations and their worldwide repercussions. To aid in the effort, here are five books that explain the gravity of the situation and what individual consumers can do to help.

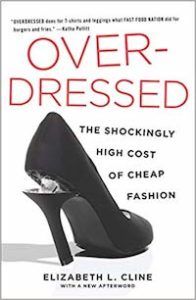

Possibly the most famous critique of fast fashion, Elizabeth Cline’s Overdressed points out that while fast fashion seem like a necessity for the American middle class, it actually imperils it by draining vital factory jobs. America produces 2% of its clothing now, compared to 50% in 1990, and while this shift has allowed for even cheaper goods, it’s also decimated the purchasing power of those who buy them. Cline also takes her reader to a factory in Guangdong, China, where low wages and lack of unions trap migrant workers in appalling working conditions—arguing that by buying from fast fashion brands, consumers become complicit in a labor system reminiscent of slavery.

Analyzing the fashion industry from a Marxist perspective, Tansy Hoskins’s Stitched Up reveals that it’s corporate interests—not consumers or workers—who profit most from cheap clothes. Hoskins adeptly points out that many abuses perpetrated by global corporations lie at the intersection of environmental and human rights. One of her case studies examines Uzbekistan’s Aral Sea; once one of the world’s largest inland bodies of water, it has now dried up completely after being used to irrigate cotton crops for the textile industry. The destruction of the Aral Sea has not only harmed the local environment but irrevocably altered the lives and livelihoods of the surrounding communities.

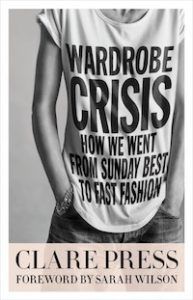

In 2013, sudden fires caused five unsafe textile factories in Dhaka, Bangladesh, to collapse, killing 1,133 workers. The incident gained international attention because several worldwide brands—including Benetton, Primark, and Mango—were known to produce clothes in these factories, indifferent to the working conditions that precipitated the tragedy. Clare Press uses this incident as the springboard for Wardrobe Crisis, which explores the role of global corporations in suppressing labor rights in the developing world and evading accountability to consumers. Press picks up the situation in Dhaka where news coverage left off, reporting that although several brands promised to improve their practices in the wake of the collapse, both wages and factory conditions have remained largely stagnant.

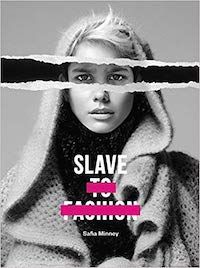

Using connections she developed as the founder of pioneering fair trade brand People Tree, Safia Minney depicts this crisis through a series of interviews with exploited workers around the world in her book of “microdocumentaries,” Slave to Fashion. Pointing out that the fashion industry permits and sometimes relies on human trafficking to function, this book makes a stark connection between fast fashion corporations and the perpetuation of modern slavery.

Compared to powerful and strategic corporations, it often seems that individuals have little power. But both Press and Minney point to activists who are advocating impressively for textile workers’ rights. And if you’re looking for ways to change your personal consumption, check out Minney’s second book, Slow Fashion: Aesthetics Meets Ethics, which outlines the methods used by ethical entrepreneurs and gives tantalizing glimpses of eco concept stores spring up all over the world.

It’s difficult to read about the ways in which our daily actions fuel a global crisis. At the same time, these books reveal the potential of our purchases to effect change: clothing brands rely on us for survival, and by demonstrating that social and environmental justice influence consumer choices, we can induce them to shift their behavior. Ultimately, that’s something to get excited about.