Can I Be a Feminist and Still Enjoy Chick Lit?

It’s 9:52pm on June 4th, 2018. I am tweeting about a bookish dilemma.

A happy bookish problem: in two hours I will get my pre-ordered copies of @LWeisberger 's #WhenLifeGivesYouLululemons and @Backmanland 's #UsAgainstYou and I don't know which to read first. #amreading

— Cecilia Lyra (@ceciliaclyra) June 5, 2018

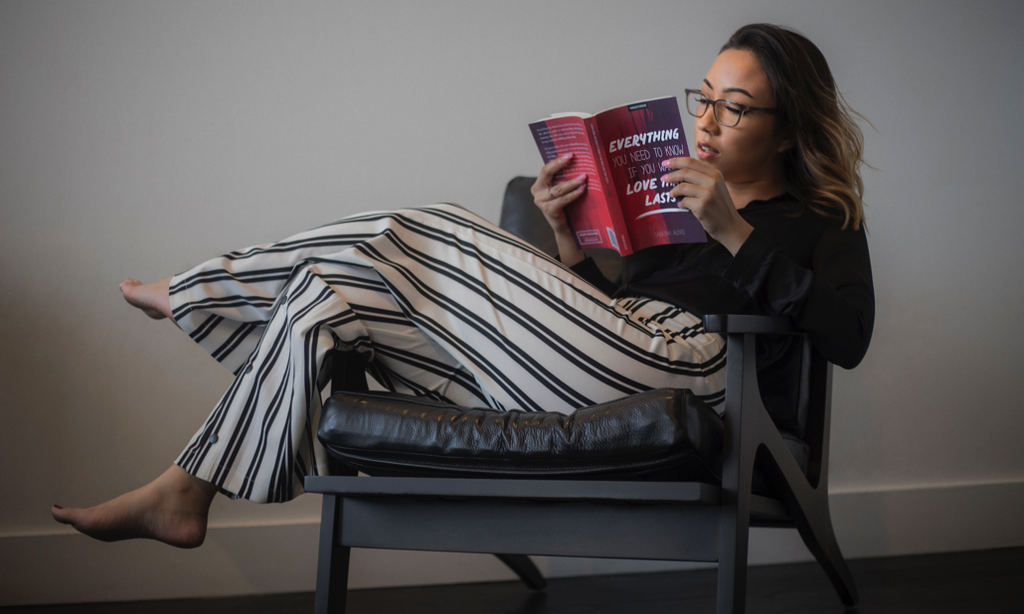

But as I begin to scroll down my Twitter feed I realize that there is no actual doubt, no real indecision. My heart is racing, and I’m biting the inside of my cheeks like they’re made of Prosecco gummy bears. I know these signs: I’m stressed, anxious. I need comfort and relief and distraction. I need the bookish equivalent of getting drunk on sunlight and rosé, while chatting with my girlfriends.

I need When Life Gives You Lululemons by Lauren Weisberger.

And so, when the clock strikes midnight, I open my iPad. Sure enough, it’s done that magical thing where it delivers me a book without asking me to interact with people or get up from my bed. (Best. Invention. Ever.)

I read and read…and read some more.

I finish the book on June 6th, before I’ve had my morning coffee. Not an impressive task: I had a lot of free time and Weisberger’s writing is like silk: smooth and alluring. Come to think of it, her themes are also satiny: light, luxurious, and more than a little sexy. And, if I’m being perfectly honest, superfluous. Given my stress level, superfluous was exactly what I needed.

It was the perfect pick-me-up.

This is what I am thinking about when see a review for When Life Gives You Lululemons. A review with one-star rating. This is like catnip to my curiosity: I am weirdly attracted to reading negative reviews about books that I enjoyed. I click on it. The reader has written a lengthy and thoughtful opinion about Weisberger’s novel. Oddly enough, she points out quite a few things she liked about it. Strange, I think. Then I reach the end. In her final sentence, she expresses that while she found the novel to be fun and well written, she could not say she enjoyed it because she is a feminist, and this means that she cannot enjoy chick lit.

I blink once, then twice. The words are still there: As a feminist, I cannot enjoy chick lit.

As a lover of the genre dubbed by the patriarchal publishing industry as chick lit, this baffles me. As a vocal and unapologetic feminist, this enrages me.

The words bounce around in my mind for the rest of day. I can’t stop thinking about them. I go back to what I loved about When Life Gives You Lululemons. I think of how anxious I had been feeling when I picked it up. And of how I felt when I was done: happy, satisfied, and…relaxed.

And relaxed is most definitely not an adjective I frequently use to describe myself.

I spend an inordinate amount of time anticipating ways in which things can go wrong. I worry as much as I eat chocolate (and I eat a lot of chocolate). I am an anxious person by nature. And yet Lauren can make me lose myself in a story. She has the power to craft worlds and characters so utterly engrossing that, for a few hours, I am fully distracted from whatever problems are permeating my brain.

Lauren is not alone in her talent. Emily Giffin also possesses the supernatural ability of making me temporarily embrace the Hakuna Matata spirit. Of all her books, Baby Proof is my favorite, and I was lucky enough to receive an advance copy of All We Ever Wanted to review for The Girly Book Club and adored it. Elin Hilderbrand is another master of escapism. A curious thing, as most of Hilderbrand’s novels tackle serious themes (mental illness, opioid addiction, blended families), but she somehow manages to do so in a way that is respectful, yet light. The Rumor brought me more comfort than brigadeiro. (If you don’t know what that is, please google it—and make it at home. It’s heaven.)

Authors like Weisberger, Giffin, and Hilderbrand write stories that make their readers feel good. It’s a form of bookish hypnotism.

And there’s value in that.

I have plenty of friends who wouldn’t touch When Life Gives You Lululemons with a ten-foot pole. They are not the type to enjoy a lighthearted, carefree novel. Some of them love horror stories while others prefer the sound logic of nonfiction. That is perfectly fine, of course. A Lauren Weisberger novel is not for everyone. But what, I wonder, is so damningly un-feminist about When Life Gives You Lululemons? If anything, it’s a feminist read. Sure, it throws around the word bitch affectionately. (I’m not a fan of that.) And I would’ve preferred a little less designer brand name dropping. (It got dizzying at times.) But it also features three driven, ambitious female characters, one of whom runs a successful business and another who supports her trust-fund baby husband. It discusses what it means to be a mother, how women feel when they quit their jobs to stay at home, and the importance of female friendships. In fact, at the heart of this novel is perhaps the most important feminist message of all: women supporting other women.

Did When Life Gives You Lululemons change my life? No. Having read all of her titles (my favorite is Last Night at Chateau Marmont), I can confidently say that there is little that is essential about a Lauren Weisberger novel. Unlike other books that I recently read and loved (Girls Burn Brighter by Shobha Rao and Shrewed by Elizabeth Renzetti), I’ve never finished an LW novel and thought to myself, Holy smokes, this should be mandatory reading! (Although I did immediately text my friends to recommend it.)

When Life Gives you Lululemons did not shed light on the plight of a marginalized community (The Break by Katherena Vermette). It did not make me question a longstanding belief (Educated: A Memoir by Tara Westover). I did not spend any amount of time contemplating its relevance and urgency given our current sociopolitical climate (The Inconvenient Indian by Thomas King). It did not make me see the world in a different, more colorful way (Precious Cargo by Craig Davidson). It did not make me feel gutted and raw (A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara).

But so what?

Books don’t have to be one thing. They don’t have to serve a single, unbending function.

Books can be anything and everything. (Incidentally, this is also true of women.)

A disclaimer: I am not a fan of the label chick lit (unless it refers to a book about a young bird). I wholeheartedly agree with Jojo Moyes, who pointed out that the term is “reductive and disappointing”. There is no denying that its origins are sexist—why else would a novel like The Marriage Plot by Jeffrey Eugenides not get labelled as chick lit when The Engagements by Curtis Sittenfeld did? Still, I don’t fault the reviewer for using it. It’s a common term—and one that many fans of Weisberger, Giffin, and Hilderbrand would use as a massive and heartfelt compliment. There is great power in taking back words and maybe these three authors feel positively about the epithet. Maybe they dislike it. I don’t know. I am not here to suggest that it should be accepted, nor am I here to say that it should be eradicated from the bookish dictionary.

What I am here to say is this: I can be a feminist and still appreciate chick lit (or whatever else you want to call it). To the aforementioned reviewer, I kindly add: feel free to enjoy whatever you want, be it Simone de Beauvoir, Roxane Gay, or Delia Ephron—or all of them! Nothing about feminism should limit women. The social right to like—or dislike—any book, free of judgment, is an essential part of what it means to be a feminist. Because books are choices. They are freedom. And these are things all women need.