The Most Important Children’s Book You’ve Never Heard of

This is a guest post from Daisy Johnson. I read, write and research children’s books. I’m also a librarian, blogger, and I make pretty amazing chocolate brownies. Cake and books, what’s not to love? Follow her on Twitter @chaletfan.

Imagine this.

It’s 1940, and you’re a British writer for children. You’re fairly well established. You’ve been doing this for over fifteen years, and you’ve got a good handful of titles under your belt. Your work is popular – you don’t know this yet, what with time travel not having been invented, but in nineteen years you’re even going to have a fan club.

But right now, you’re faced with a choice. Do you acknowledge the seismic horror of the Second World War in your work or do you not? Some of your fellow writers sail into a world full of idealism and Arcadia, and become increasingly defined by this otherworldly romanticism, whilst others take a contrary view and write this brave new world into their stories. Air raids, rationing. Stiff upper lips and patriotic fervour. Rule Britannia.

But you, you brilliant, wonderful thing you, you decide to do things a little differently.

You write a book that faces the war head on. You stubbornly, deliberately, point out the difference between Germans and Nazis, even as you tackle themes of Gestapo persecution, racial identity, and political machinations. You let some of your characters express the inexpressible, and the indefensible, whilst others fight back with words, and belief, and hope. You show your readers that because the good people survive, they too will live. You write a book defined by female language and the strength of it, and you talk about occupation and aggression and war and you tell your readers that there’s a way through it all.

You tell them that resistance, hope and empathy wins.

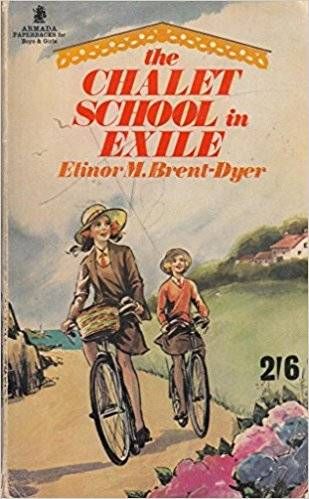

Let’s stop imagining for a moment, and talk facts. I’ve been telling you about a book called The Chalet School in Exile, which was written back in 1940 by a middle-aged British writer called Elinor M. Brent-Dyer, and I think it might be the most important book you’ve never heard of. Children’s literature is a political space and some authors have always been more comfortable than others in addressing that. But here’s the thing: you can’t ever run from that politicised edge. From the way that a book’s placed on the shelf, through to the genders, sexualities, and identities that are presented, each book that’s out there says something, whether it wants to or not.

Let’s stop imagining for a moment, and talk facts. I’ve been telling you about a book called The Chalet School in Exile, which was written back in 1940 by a middle-aged British writer called Elinor M. Brent-Dyer, and I think it might be the most important book you’ve never heard of. Children’s literature is a political space and some authors have always been more comfortable than others in addressing that. But here’s the thing: you can’t ever run from that politicised edge. From the way that a book’s placed on the shelf, through to the genders, sexualities, and identities that are presented, each book that’s out there says something, whether it wants to or not.

So the next time you’re in a second hand bookshop, or have some money to spend online, seek out The Chalet School in Exile. Read it alongside The Journey by Francesca Sanna, or A Is For Activist by Innosanto Nagara, and share it with your children and the children you talk to and the children you work with, because it’s a book that, however much it pains me, still has so much to say about the world that we live in today. As the headmistress,Miss Annersley says, “There are terrible forces of evil abroad in the world and we, as a School, must do our share towards ending them.” We may not be at school, we may be several years or generations past school, but we can champion those books that question and challenge the world when it’s gone a little wrong. And when it comes down to the books that do that, The Chalet School in Exile is probably the most important book you’ve never heard of.

But now you know its name.