Hey Book Industry: “Women’s Fiction” Is Not a Thing

I love a lot of books that we think of as “women’s fiction.” But I absolutely hate the fact that we call them “women’s fiction.” In fairness, many women – including both readers and authors – don’t have an issue with the categorization. But I do. Big time.

The definition of “women’s fiction” is a little unclear. The most problematic definition would be fiction that is geared toward women. The sexism inherent in the assumption that Ivanka Trump, Venus Williams, Sonia Sotomayor, and my 3rd grade teacher all want to read the exact same books just because each is an adult female human is astounding.

The definition of “women’s fiction” is a little unclear. The most problematic definition would be fiction that is geared toward women. The sexism inherent in the assumption that Ivanka Trump, Venus Williams, Sonia Sotomayor, and my 3rd grade teacher all want to read the exact same books just because each is an adult female human is astounding.

A more generous definition of “women’s fiction” is fiction written about and usually by women. This one is slightly better because at least there is some metric for the category that can be defined with some level of success. It’s easier to determine whether a book is about or by a woman than it is to determine if it is for all women.

That definition is still riddled with problems, though. Here are some reasons why “women’s fiction” is a category that’s not just useless, but actually destructive.

It’s arbitrary. Generally speaking, separating books by genre makes sense. It helps mystery readers find mysteries, romance readers find romance, and memoir readers find memoirs. But the term “women’s fiction” tells you almost nothing about the content and formula of the book you’re about to read other than the fact that it’s fiction and there’s almost certainly a woman in it.

Think of it this way: if you were book browsing and encountered a category called “Fiction by people with brown eyes,” you’d probably think it was strange. The same is probably true of sections of fiction specifically about “People Who Are Taller than Average,” or “People Who Live in the US Central Time Zone.” Each of those categories has a commonality, but it has nothing to do with the kind of fiction a person would want to read. And yet (perhaps you’ve guessed where I’m going with this), there is an entire subset of fiction that has been grouped together based on the sex or gender identity of the author or characters.

Think of it this way: if you were book browsing and encountered a category called “Fiction by people with brown eyes,” you’d probably think it was strange. The same is probably true of sections of fiction specifically about “People Who Are Taller than Average,” or “People Who Live in the US Central Time Zone.” Each of those categories has a commonality, but it has nothing to do with the kind of fiction a person would want to read. And yet (perhaps you’ve guessed where I’m going with this), there is an entire subset of fiction that has been grouped together based on the sex or gender identity of the author or characters.

It’s sexist: As I said, at best, “women’s fiction” books are about women and written by women. Which, fine. But there’s no “men’s fiction” subgenre for books about or by men. Somehow, booksellers manage to find space for books by and about men in categories like “Humor & Satire” or “Historical Fiction.” Or literally all of the other categories.

While there are female authors in those sections too, many of them get shuffled over to the “Women’s Fiction” section. There’s a big problem with sexism in the literary world, but it’s particularly blatant to take an entire category of books and authors and segregate them this way.

It’s gender-binary: As a society, we’re gaining more and more understanding about the fluidity of gender. We have a very long way to go in furthering that understanding and being fully inclusive of people of all different sex and gender identities. Creating a superfluous sex or gender-specific categorization around books hinders our already slow progress.

It allows for stereotyping that impacts sales and other metrics of success: I have lots of intelligent, progressive friends who won’t read “women’s fiction” despite the fact that they can’t articulate exactly what it is. It’s unlikely that every one of these men and women would connect with every book in the “women’s fiction” section, but they avoid them all based on a meaningless descriptor and the stereotypes that surround it.

It allows for stereotyping that impacts sales and other metrics of success: I have lots of intelligent, progressive friends who won’t read “women’s fiction” despite the fact that they can’t articulate exactly what it is. It’s unlikely that every one of these men and women would connect with every book in the “women’s fiction” section, but they avoid them all based on a meaningless descriptor and the stereotypes that surround it.

Categorization becomes a very real issue for not just sales, but also other kinds of recognition. Richard Russo and Terry McMillan both write contemporary fiction about adults navigating life, work, and relationships, but only one of them gets tagged as a “women’s fiction” writer. And it’s not the one whose book won a Pulitzer Prize.

This is not a hard problem to solve: Maybe every single book that wins awards is better than every single book categorized as “women’s fiction.” But the fact that a book is by or about a woman shouldn’t box it out of the same kinds of consideration as a book by and/or about a man. Maybe not every “women’s fiction” book should be considered “literary fiction.” That’s fine with me. But then let’s actually put them in categories that are based on the content of the book as opposed to whether or not the author or main character is in possession of lady parts.

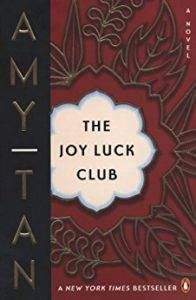

It’s not difficult: Liane Moriarty’s Big Little Lies could fit nicely in “mystery” or “humor” or both. The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society, by Annie Barrows and Mary Ann Shaffer, is historical fiction and an epistolary novel. And if Barnes & Noble has room for a section called “New Paranormal Teen Romance,” surely they can create an “Intergenerational Family Fiction” space for Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club. Maybe Jonathan Tropper’s This is Where I Leave You or – heresy alert! – Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections can sit there too.

It’s not difficult: Liane Moriarty’s Big Little Lies could fit nicely in “mystery” or “humor” or both. The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society, by Annie Barrows and Mary Ann Shaffer, is historical fiction and an epistolary novel. And if Barnes & Noble has room for a section called “New Paranormal Teen Romance,” surely they can create an “Intergenerational Family Fiction” space for Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club. Maybe Jonathan Tropper’s This is Where I Leave You or – heresy alert! – Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections can sit there too.

As it turns out, sometimes man-humans are part of families and communities and relationships, too. Let’s do something wild and crazy and actually sort books in a way that reflects that reality.