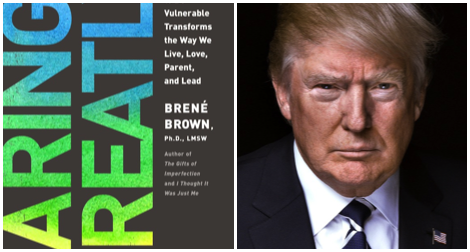

Brené Brown, Vulnerability, and the Trump Voter

Due to her extremely famous TED talk, I am probably late in discovering Brené Brown and her groundbreaking research on shame and vulnerability. Her book Daring Greatly: How the Courage to be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent and Lead, has been out since 2012, but I only recently picked it up.

Due to her extremely famous TED talk, I am probably late in discovering Brené Brown and her groundbreaking research on shame and vulnerability. Her book Daring Greatly: How the Courage to be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent and Lead, has been out since 2012, but I only recently picked it up.

Brown researches human connection and how shame – the fear of disconnection, of not being worthy or good enough for connection – can fragment or destroy it. In Daring Greatly she reveals that shame resilience and the ability of opening up to vulnerability are the only way to live a whole-hearted life. Brown uses her findings to teach how we can better the workplace and the home, but I unexpectedly started to consider how being whole-hearted can help me resist, as an activist, writer, and academic, in an age of fascism and right-wing dominance.

Brown discusses aspects of Western culture that stop us from being whole-hearted (or, living a happy, fulfilled life). Among many issues she points out, there’s the fear of being wrong, the fear of messing up and of being publicly shamed (which is magnified by the age of social media in which we currently live in). I have come to see President elect Donald Trump as the manifestation of very harmful parts of Western culture: toxic masculinity, arrogance, lack of humility, the need for domination and the hunger for power. How many times have we seen Trump make ignorant, bigoted claims and — when being shamed and called out for saying those things — double down on his statements?

And from this behaviour, exhibited by a man whose power will soon be completely disproportionate to his qualifications to handle said power, seems to encourage others to behave in the same way. How many times have I personally encountered trolls and Nazis online who have no evidence or argument behind their claims except for “It’s my opinion” and “Free speech!!”? In the last few months, how many Trump supporters have yelled or typed in all-caps that they aren’t deplorable or racist, that they are really good people, when marginalised people point out that voting for a bigot isn’t acceptable? How many times in the last few years of existing as a female writer online have I been called a cunt, a whore, a bitch?

Lashing out, violently, at people who dislike your views has become the new normal. I don’t believe the people who call me a bitch online even think about it again after they send the message. They’ve gone as far as they want to: they’re shamed me for being a woman, called me names for doing my job or weaving a critique of pop culture. As soon as they send that message, they move on and stay where they are, forever paralized in their perceived rightness and avoidance of shame.

And Brown’s discussion of how the mismanagement of shame can result in disengagement in personal and professional relationships has led me to think about how the current configuration of political engagement is political disengagement: much has been said about how the ascension of Trump is about how he is not a politician, about how different he appears to be from the political elite because he says all kinds of ignorant, thundering statements like, “Build a wall,” or “Lock her up.” Trump signified to many the destruction of a system that they didn’t want to engage with anymore. Whatever their reasons for this — and look, I personally think it’s about looking at a changing world, where marginalised people are gaining rights, and being uncomfortable and afraid of a system that fosters that change — I believe it’s important to consider whether the ascension of Trump is a direct result of disengagement, be it by people who voted for him and wanted to watch the world burn because of their own fear and shame, or by people who didn’t vote at all because they are politically disenfranchised because of class, race, gender, sexual orientation and/or ability. Also, it must be noted that if people voted for Trump despite all his bigotry, claiming that it was really all about his economic policies, that would also qualify as disengagement.

Yelling that you aren’t a racist, a sexist, a transphobe or a bigot because you voted for Trump doesn’t mean you aren’t those things. It means that, in addition to you being those things and voting accordingly, you are increasingly afraid of not being worthy of connection because of your values. It means Trump supporters are ashamed of living in a world where those values are increasingly seen as unacceptable, where a woman can run for president and win the popular vote, where the President is black and speaks out for trans people.

I see this trend in push backs against social justice movements all the time. In the whole #NotAllMen/#YesAllWomen debacle, for example, the shame of benefiting from male privilege rears its ugly head and stonewalls any discussion of how men could help educate their peers on toxic masculinity. The focus on denying charges of wrongdoing or privilege instead of on being open to re-assessing values and world views is at the heart of the lack of political dialogue today.

Brown asserts that shame fosters disengagement because being vulnerable to re-assessing your values and how you approach life is too painful, too shameful. Of course, we’ve all had moments in our lives where we stomped our feet and refused to admit we are wrong, we’ve all had our double-down moments where shame has taken over. But what happens when–in addition to a culture that encourages this behaviour–one of the most powerful men in the world has demonstrably thrived by acting this way? How do we fight in a society that has become so afraid, hateful and arrogant that fake news and post-fact reporting like Breibart is taking over people’s minds and lives?

I can only speak for myself and I won’t pretend to be a preacher (although, here’s a practical guide for Americans on how to fight Trump and here’s one for people who don’t live in the USA). I will fight for my side fiercely, I will continue to speak out for the rights of marginalised people, I will continue to write and research with social justice in mind. But in addition to that, I believe Brown’s conclusions can be used in my activism.

Brown’s research not only determines that shame is the source of most human connection problems, but also reveals that shaming people for their views or issues doesn’t work as a strategy for change. This has been hard for me to swallow because it’s very difficult not to mock Trump because he’s a bully, an awful person who continues to reveal himself as even more horrible everyday that passes. And I’m not about to pledge to stop mocking him, nor am I saying that I am going to approach Trump supporters with the solitary mission of changing their minds (especially because studies say that a change of mind happens incrementally, so I doubt I could convince an online troll to not be a bigot with one empathetic Twitter conversation). But I want to resist the urge to be as angry, disengaged and fearful as people I encounter online seem to be. I want to resist the urge of seeing people, online and off, as one-dimensional and extend empathy even to people who seem to hate me and who I am. I want to be vulnerable enough to always question myself and possible fake news that feeds into my timeline, even if they seem to prove my opinions are well-founded. I want to strive for nuanced critiques, rather than one-tweet takes that make everyone stop listening to each other. Part of resisting Trump and his messaging, I am finding, is striving towards empathy, vulnerability and conversations rather than screaming matches.

Brown calls this approach “the tightrope”; it’s the constant balancing of allowing for vulnerability, but within your imposed boundaries. Brown stresses this throughout her book: boundaries are the key to vulnerability. For activists, writers and academics who believe in social justice, it might be a hard pill to swallow: recharging and stepping away from certain battles is essential for bringing about change in the world. The vulnerability of being open to dialogue depends on it: if those of us who stand against Trump are constantly fighting, inwardly and outwardly, he will win.

The way I see it, it’s a balance between accountability and self-care. We cannot care for others if we do not care for ourselves. But this doesn’t mean we have to be individualistic and not care about what people think either: being accountable for mistakes and our own blind spots is important too. Resisting fascism is partly about refusing to give into the hatred and shame that has put us here in the first place; it’s giving space to vulnerability and empathy despite being told not to. Don’t give in. Resist.