“[T]hose librarians failed students”: Book Ban at Irving Independent School District

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Update, 7/11: New information from a current English teacher at Irving High School.

Cecelia Holden reached out after seeing this post.

“Actual Irving High School teacher here and have been at the campus for going on 4 years. [. . . ] these books were distributed to the other English teachers and remain on campus. I have had half a dozen LGBT students read Love is Love on their own time and enjoy it.”

She notes that while Waugh’s information about books being pulled from curriculum is correct, those books were returned to teachers for classroom use.

“All of the graphic novels were returned from being reviewed with bookmarked pages of inappropriate images or text. What caused Love is Love to be removed from the curriculum was the GRAPHIC violence depicted of the Pulse shooting. Monster was flagged for language, Speak for sexual content,” Holden clarified.

She added that the books are prominently in her classroom, “[K]ids still have access to them if they choose to seek them out!”

Previously reported: It’s easy to believe that book bans don’t happen and that books aren’t pulled from library or classroom shelves. It’s far easier and more damaging to think that books being banned is a badge of honor or that it doesn’t impact readers in a digital age. But neither of these statements are true. Censorship remains alive and well, and books that are censored mean that readers are left to discover them on their own or that they’ll have access only if they have the means to access them (financial or otherwise). The Irving Independent School District (Irving ISD) in Irving, Texas, a suburb of Dallas and the thirteenth most populated city in Texas, has, according to one former teacher, gone to significant lengths to hide an ongoing ban of LGBTQ material from the curriculum. Anna Waugh is a former English I teacher with the district. She, along with fellow members of her team, worked to build a social justice unit in the spring of 2018. “What followed was the sudden removal of all six novels from the unit because of one LGBT-themed text. This was followed by silence from leadership, an eventual cover-up by the district, and a new policy gatekeeping teacher-selected materials,” she wrote in a letter to The Dallas Voice. The Irving Schools Foundation provided a grant for this new curriculum to purchase six graphic novels. Those included Laurie Halse Anderson’s Speak, Walter Dean Myers’s Monster, John Lewis’s March, Marc Andreyko’s Love Is Love, Cory Doctorow’s In Real Life, and “We purposefully chose books on topics our freshman students could relate to — bullying, sexual abuse, child labor, violence, the prison industrial complex and bigotry — because circulation date demonstrated that students were checking out three graphic novels to every five fiction books. We planned to have students self-select two from the set,” said Waugh. She added that the project had overwhelming support from the principal, who’d suggested to her and fellow teacher and project coordinator Carol Revelle to seek funding from the foundation. The principal also attended the grant presentation.

Research shows that comics are not only increasingly popular among young readers but that they’re also educationally valuable.

According to Leslie Morrison with Northwestern University, “With graphic novels, students use text and images to make inferences and synthesize information, both of which are abstract and challenging skills for readers. Images, just like text, can be interpreted in many different ways, and can bring nuances to the meaning of the story. In this form of literature, the images and the text are of equal importance—the text would not fully make sense without the images, and the reverse is true as well.”

Everything looked like it was ready to roll, until Waugh and Revelle began laminating the covers of the books two days prior to the start of the unit.

“The principal entered the room and told us to pack up the books because a complaint had reached the superintendent,” said Waugh. “Revelle — who has a doctorate in curriculum and instruction and more than two decades of teaching experience — emailed a letter the next day, requesting an immediate return of the novels and that the district follow its policy for challenged materials.”

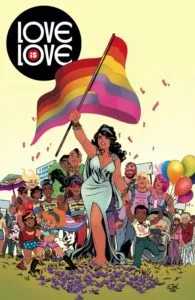

Revelle, Waugh, and the rest of the English I team received no response. As word began to spread about the complaint, support for the curriculum — specifically, for the use of Love Is Love, a comic that celebrates LGBTQ+ people, created to mourn victims and support survivors of the Orlando Pulse Nightclub Shooting in 2016 — disappeared.

Without consulting the department, several librarians and the superintendent met to discuss the books and decided to pull Love Is Love from the curriculum.

“Our librarian repeated a rumor that the committee took issue with the novel’s “extreme homosexuality.” I have thought long and hard about that description and can only say that it’s a hateful depiction for a graphic novel that memorializes the victims of the 2016 Pulse Nightclub shooting, and that proceeds from the sale benefit the survivors of the deadliest attack on the LGBT community in U.S. history,” Waugh said.

Waugh, who is lesbian, added, “The text is tasteful and respectful and, sadly, representative of this tragic event in our community’s history.”

“We purposefully chose books on topics our freshman students could relate to — bullying, sexual abuse, child labor, violence, the prison industrial complex and bigotry — because circulation date demonstrated that students were checking out three graphic novels to every five fiction books. We planned to have students self-select two from the set,” said Waugh. She added that the project had overwhelming support from the principal, who’d suggested to her and fellow teacher and project coordinator Carol Revelle to seek funding from the foundation. The principal also attended the grant presentation.

Research shows that comics are not only increasingly popular among young readers but that they’re also educationally valuable.

According to Leslie Morrison with Northwestern University, “With graphic novels, students use text and images to make inferences and synthesize information, both of which are abstract and challenging skills for readers. Images, just like text, can be interpreted in many different ways, and can bring nuances to the meaning of the story. In this form of literature, the images and the text are of equal importance—the text would not fully make sense without the images, and the reverse is true as well.”

Everything looked like it was ready to roll, until Waugh and Revelle began laminating the covers of the books two days prior to the start of the unit.

“The principal entered the room and told us to pack up the books because a complaint had reached the superintendent,” said Waugh. “Revelle — who has a doctorate in curriculum and instruction and more than two decades of teaching experience — emailed a letter the next day, requesting an immediate return of the novels and that the district follow its policy for challenged materials.”

Revelle, Waugh, and the rest of the English I team received no response. As word began to spread about the complaint, support for the curriculum — specifically, for the use of Love Is Love, a comic that celebrates LGBTQ+ people, created to mourn victims and support survivors of the Orlando Pulse Nightclub Shooting in 2016 — disappeared.

Without consulting the department, several librarians and the superintendent met to discuss the books and decided to pull Love Is Love from the curriculum.

“Our librarian repeated a rumor that the committee took issue with the novel’s “extreme homosexuality.” I have thought long and hard about that description and can only say that it’s a hateful depiction for a graphic novel that memorializes the victims of the 2016 Pulse Nightclub shooting, and that proceeds from the sale benefit the survivors of the deadliest attack on the LGBT community in U.S. history,” Waugh said.

Waugh, who is lesbian, added, “The text is tasteful and respectful and, sadly, representative of this tragic event in our community’s history.”

The book was officially banned.

Waugh and Revelle were repeatedly met with silence as they spoke to district officials about the book and its value in the curriculum. They’ve also been met with roadblocks as they’ve attempted to bring this matter to organizations that could help them get the book put back into the curriculum and ultimately, the hands of young readers.

“Emails went back and forth between the district’s legal counsel and McDonnell, but the district held firm to the ban, citing a new policy that requires six-weeks’ notice for non-approved texts. This was not the policy in spring 2018, and it can only have been created to prevent future LGBT-inclusive texts,” Waugh said.

She added, “[T]he district is concealing this ban by not listing any of the graphic novels as challenged or Love is Love as banned in its records. In fact, the information obtained from the district is incomplete, as these events, as well as at least two emails, are known to be missing from records requests.”

Both teachers secured new jobs in the summer after the book’s ban, creating a further challenge for reestablishing the book into the project.

“[W]e contacted the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, but that organization needs someone associated with the school — a teacher, student, parent — to make the complaint to reverse the ban. Because Revelle and I are now employed elsewhere, I reached out to the school’s GSA advisor to see if she or the students could take on the fight with us. She spoke to another member of the team still employed who wouldn’t even talk about it, giving her, she said, the impression she needed to “keep it quiet.”,” said Waugh. “I was angry at that, yet I had waited until I had a new job before advocating for the text. We also contacted the American Library Association’s Office of Intellectual Freedom. At this point, we want the graphic novels repurchased and united with the set, and we want the new gatekeeping policy removed to allow teachers the ability to choose texts, including LGBT texts, for their students.”

Waugh desperately wishes to see Love Is Love added back into the curriculum. Of the six texts, it was the only one to be pulled and only one to not be allowed for classroom use. She’s remorseful for not pushing harder when the book was initially challenged. Though the book has no professional reviews, she noted that other books used in the curriculum lack those reviews as well. Further, it’s often difficult for comics to be reviewed in the same way novels and nonfiction are.

“At the end of the day, the LGBT students of Irving ISD deserve to see themselves represented in the curriculum and to have their stories told, not erased like the district has done with its recordkeeping,” she said.

Though Waugh may be unable to advocate from within the system, there are ways others can push back against such censorship.

Want to do something? Here are some steps to take in the fight to bring the book back into the curriculum and shed light on censorship:

The book was officially banned.

Waugh and Revelle were repeatedly met with silence as they spoke to district officials about the book and its value in the curriculum. They’ve also been met with roadblocks as they’ve attempted to bring this matter to organizations that could help them get the book put back into the curriculum and ultimately, the hands of young readers.

“Emails went back and forth between the district’s legal counsel and McDonnell, but the district held firm to the ban, citing a new policy that requires six-weeks’ notice for non-approved texts. This was not the policy in spring 2018, and it can only have been created to prevent future LGBT-inclusive texts,” Waugh said.

She added, “[T]he district is concealing this ban by not listing any of the graphic novels as challenged or Love is Love as banned in its records. In fact, the information obtained from the district is incomplete, as these events, as well as at least two emails, are known to be missing from records requests.”

Both teachers secured new jobs in the summer after the book’s ban, creating a further challenge for reestablishing the book into the project.

“[W]e contacted the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, but that organization needs someone associated with the school — a teacher, student, parent — to make the complaint to reverse the ban. Because Revelle and I are now employed elsewhere, I reached out to the school’s GSA advisor to see if she or the students could take on the fight with us. She spoke to another member of the team still employed who wouldn’t even talk about it, giving her, she said, the impression she needed to “keep it quiet.”,” said Waugh. “I was angry at that, yet I had waited until I had a new job before advocating for the text. We also contacted the American Library Association’s Office of Intellectual Freedom. At this point, we want the graphic novels repurchased and united with the set, and we want the new gatekeeping policy removed to allow teachers the ability to choose texts, including LGBT texts, for their students.”

Waugh desperately wishes to see Love Is Love added back into the curriculum. Of the six texts, it was the only one to be pulled and only one to not be allowed for classroom use. She’s remorseful for not pushing harder when the book was initially challenged. Though the book has no professional reviews, she noted that other books used in the curriculum lack those reviews as well. Further, it’s often difficult for comics to be reviewed in the same way novels and nonfiction are.

“At the end of the day, the LGBT students of Irving ISD deserve to see themselves represented in the curriculum and to have their stories told, not erased like the district has done with its recordkeeping,” she said.

Though Waugh may be unable to advocate from within the system, there are ways others can push back against such censorship.

Want to do something? Here are some steps to take in the fight to bring the book back into the curriculum and shed light on censorship:

Previously reported: It’s easy to believe that book bans don’t happen and that books aren’t pulled from library or classroom shelves. It’s far easier and more damaging to think that books being banned is a badge of honor or that it doesn’t impact readers in a digital age. But neither of these statements are true. Censorship remains alive and well, and books that are censored mean that readers are left to discover them on their own or that they’ll have access only if they have the means to access them (financial or otherwise). The Irving Independent School District (Irving ISD) in Irving, Texas, a suburb of Dallas and the thirteenth most populated city in Texas, has, according to one former teacher, gone to significant lengths to hide an ongoing ban of LGBTQ material from the curriculum. Anna Waugh is a former English I teacher with the district. She, along with fellow members of her team, worked to build a social justice unit in the spring of 2018. “What followed was the sudden removal of all six novels from the unit because of one LGBT-themed text. This was followed by silence from leadership, an eventual cover-up by the district, and a new policy gatekeeping teacher-selected materials,” she wrote in a letter to The Dallas Voice. The Irving Schools Foundation provided a grant for this new curriculum to purchase six graphic novels. Those included Laurie Halse Anderson’s Speak, Walter Dean Myers’s Monster, John Lewis’s March, Marc Andreyko’s Love Is Love, Cory Doctorow’s In Real Life, and

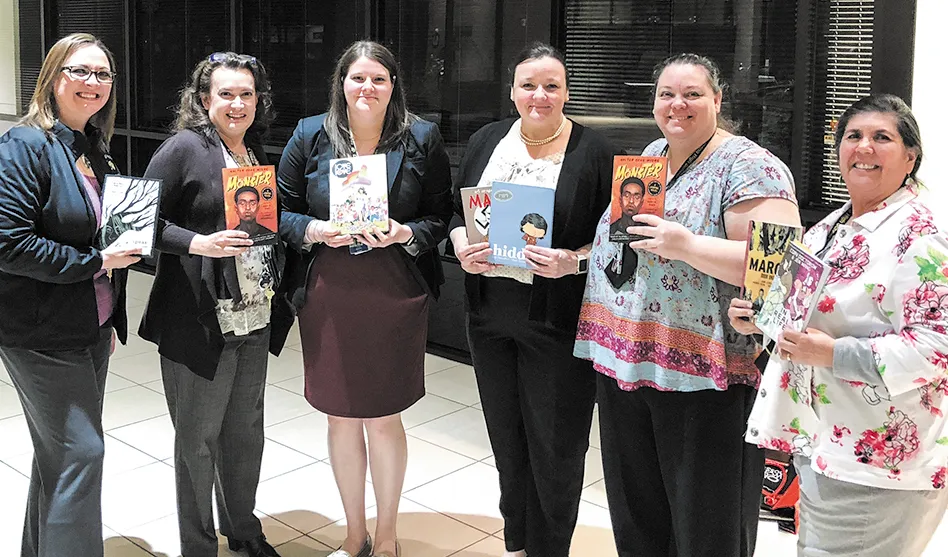

Photo from Anna Waugh, via her piece in the Dallas Voice

The book was officially banned.

Waugh and Revelle were repeatedly met with silence as they spoke to district officials about the book and its value in the curriculum. They’ve also been met with roadblocks as they’ve attempted to bring this matter to organizations that could help them get the book put back into the curriculum and ultimately, the hands of young readers.

“Emails went back and forth between the district’s legal counsel and McDonnell, but the district held firm to the ban, citing a new policy that requires six-weeks’ notice for non-approved texts. This was not the policy in spring 2018, and it can only have been created to prevent future LGBT-inclusive texts,” Waugh said.

She added, “[T]he district is concealing this ban by not listing any of the graphic novels as challenged or Love is Love as banned in its records. In fact, the information obtained from the district is incomplete, as these events, as well as at least two emails, are known to be missing from records requests.”

Both teachers secured new jobs in the summer after the book’s ban, creating a further challenge for reestablishing the book into the project.

“[W]e contacted the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, but that organization needs someone associated with the school — a teacher, student, parent — to make the complaint to reverse the ban. Because Revelle and I are now employed elsewhere, I reached out to the school’s GSA advisor to see if she or the students could take on the fight with us. She spoke to another member of the team still employed who wouldn’t even talk about it, giving her, she said, the impression she needed to “keep it quiet.”,” said Waugh. “I was angry at that, yet I had waited until I had a new job before advocating for the text. We also contacted the American Library Association’s Office of Intellectual Freedom. At this point, we want the graphic novels repurchased and united with the set, and we want the new gatekeeping policy removed to allow teachers the ability to choose texts, including LGBT texts, for their students.”

Waugh desperately wishes to see Love Is Love added back into the curriculum. Of the six texts, it was the only one to be pulled and only one to not be allowed for classroom use. She’s remorseful for not pushing harder when the book was initially challenged. Though the book has no professional reviews, she noted that other books used in the curriculum lack those reviews as well. Further, it’s often difficult for comics to be reviewed in the same way novels and nonfiction are.

“At the end of the day, the LGBT students of Irving ISD deserve to see themselves represented in the curriculum and to have their stories told, not erased like the district has done with its recordkeeping,” she said.

Though Waugh may be unable to advocate from within the system, there are ways others can push back against such censorship.

Want to do something? Here are some steps to take in the fight to bring the book back into the curriculum and shed light on censorship:

The book was officially banned.

Waugh and Revelle were repeatedly met with silence as they spoke to district officials about the book and its value in the curriculum. They’ve also been met with roadblocks as they’ve attempted to bring this matter to organizations that could help them get the book put back into the curriculum and ultimately, the hands of young readers.

“Emails went back and forth between the district’s legal counsel and McDonnell, but the district held firm to the ban, citing a new policy that requires six-weeks’ notice for non-approved texts. This was not the policy in spring 2018, and it can only have been created to prevent future LGBT-inclusive texts,” Waugh said.

She added, “[T]he district is concealing this ban by not listing any of the graphic novels as challenged or Love is Love as banned in its records. In fact, the information obtained from the district is incomplete, as these events, as well as at least two emails, are known to be missing from records requests.”

Both teachers secured new jobs in the summer after the book’s ban, creating a further challenge for reestablishing the book into the project.

“[W]e contacted the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, but that organization needs someone associated with the school — a teacher, student, parent — to make the complaint to reverse the ban. Because Revelle and I are now employed elsewhere, I reached out to the school’s GSA advisor to see if she or the students could take on the fight with us. She spoke to another member of the team still employed who wouldn’t even talk about it, giving her, she said, the impression she needed to “keep it quiet.”,” said Waugh. “I was angry at that, yet I had waited until I had a new job before advocating for the text. We also contacted the American Library Association’s Office of Intellectual Freedom. At this point, we want the graphic novels repurchased and united with the set, and we want the new gatekeeping policy removed to allow teachers the ability to choose texts, including LGBT texts, for their students.”

Waugh desperately wishes to see Love Is Love added back into the curriculum. Of the six texts, it was the only one to be pulled and only one to not be allowed for classroom use. She’s remorseful for not pushing harder when the book was initially challenged. Though the book has no professional reviews, she noted that other books used in the curriculum lack those reviews as well. Further, it’s often difficult for comics to be reviewed in the same way novels and nonfiction are.

“At the end of the day, the LGBT students of Irving ISD deserve to see themselves represented in the curriculum and to have their stories told, not erased like the district has done with its recordkeeping,” she said.

Though Waugh may be unable to advocate from within the system, there are ways others can push back against such censorship.

Want to do something? Here are some steps to take in the fight to bring the book back into the curriculum and shed light on censorship:

- Write to the State Representatives from Irving, demanding an investigation into the policies leading to the book’s removal: Julie Johnson, Terry Meza, Jessica González, and Rafael Anchia. Links go directly to their email.

- Write to the State Senators from Irving: Kelly Hancock, Nathan Johnson, and Royce West.

- Irving is represented by two state board of education members. Write them and let them know about the book being removed from curriculum and the failure to follow proper recording keeping, as well as inconsistent application of policies and procedures for challenged materials: Pat Hardy and Aicha Davis.

- If you’re local, attend a school board meeting for the Irving ISD. Details on meetings and how to have items added to the agenda are online.

- Magda Hernandez is the Irving ISD superintendent, and her executive assistant is Karen Edwards. Their email addresses are available, and both should be contacted about the issue. Ask questions and demand answers. Their emails will be part of the public record. It’s also worth noting how banning a book like Love Is Love goes against the district’s very own discrimination policy.

- If you’re local — and even if you’re not — pen some letters of support for the curriculum and demand answers of the book’s removal to any and all local newspapers in the Irving, Dallas, and Fort Worth areas.

- Pressure the Office for Intellectual Freedom, as well as the Comic Book Legal Defense League, to cover this story and investigate these claims.

- If you’re local and want to take more guerrilla style efforts, purchase copies of Love is Love and donate them to local Little Free Libraries, to libraries in the area, and to the school’s LGBTQ student groups.

- If you’re not local but want to make sure that LGBTQ books are available to students in your area, look up your local schools’ curricula, and ask questions!

- Operation Caged Bird Seeks to Unban Books from Naval Academy: Book Censorship News, April 25, 2025

- It’s Still Censorship, Even If It’s Not a Book Ban: Book Censorship News, August 30, 2024

- Are You Registered to Vote?: Book Censorship News, August 23, 2024

- What Is Weeding and When Is It Not Actually Weeding?: Book Censorship News, August 16, 2024

- How To Explain Book Bans to Those Who Want To Understand: Book Censorship News, August

- A New Era for Banned Books Week: Book Censorship News, August 2, 2024

- The Ongoing Censorship of High School Advanced Placement Courses: Book Censorship News, July 26, 2024

- The Quiet Censorship of Pride 2024: Book Censorship News, July 19, 2024

- Survey: What Happened During Pride Month? Book Censorship News for July 5, 2024

- The First American Union Understood The Necessity of Public Libraries and Education: Book Censorship News for June 28, 2024