A Breadful Tale: How Bread Inspired the Mythology of My Book about Fairies

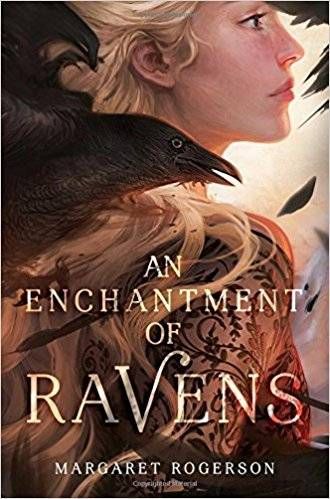

This is a guest post from Margaret Rogerson. Prior to writing her first book, Margaret Rogerson worked a variety of jobs ranging from canoe livery counter girl to graphic designer. She has a bachelor’s degree in cultural anthropology from Miami University. When not reading or writing she enjoys sketching, gaming, making pudding, and watching more documentaries than is socially acceptable (according to some). She lives near Cincinnati, Ohio, beside a garden full of hummingbirds and roses. An Enchantment of Ravens is her debut novel. Follow her on Twitter @MarRogerson.

I love carbs, but according to folklore, fairies don’t. For as long as I can remember, I’ve been fascinated by the Celtic superstition that bread can be used to repel fairies. As late as the 1880s in Ireland—possibly later—people still placed bread in their pockets when visiting locations known to be frequented by fairies, or hid it in their children’s clothes after dark to protect them from fairy mischief. Apparently, this odd crumb of folklore even traveled across the sea from Ireland to Newfoundland.

Why bread? It was associated with the hearth, and therefore humanity. As wild creatures, fairies found it repellent; perhaps it even held some kind of power over them. I have no idea when I first stumbled across the idea, or where, or why it stuck in my mind. Among the endless blur of fairy tales and fantasy novels I read over the years, the only one that I can recall dealing with bread’s folkloric significance is The Folk Keeper by Franny Billingsley. In this spectacularly unique book, the titular Folk Keeper earns her living protecting an estate from ravenous subterranean fairies, and uses bread as part of her defensive repertoire.

But the folklore is contradictory, and fairies’ relationship with bread is complicated. (Whose isn’t?) Sometimes, in fact, bread was considered an appropriate offering to leave on one’s doorstep for fairies alongside milk or cream. I puzzled endlessly over this inconsistency. Eventually, I came up with an explanation: fairies hated bread and loved it at the same time. They desperately craved what they couldn’t have. Maybe they ate it, even though it made them sick, the same way I gorged myself on Kit-Kat bars every Halloween. I never could have imagined that I’d remember my solution in the shower one morning over a decade later, and that it would inspire my first novel.

As I grew up, I became resentful of the fact that so many of the fairies available for my consumption more closely resembled Tinkerbell than Der Erlkönig. Fairies were no longer cool to me, not when they had dragonfly wings and wore buttercup dresses, and very rarely hurt people or stole human infants. I boxed up my love for fairies, placed it on a shelf in my mind and allowed it to gather dust. Then I took that particular shower that fateful morning and had the realization that I wanted to read a very specific kind of book. I wanted it to remind me of a Robin McKinley fairy tale, and I wanted it to have traditional fairies in it—not perfect, elf-like fairies, but the nasty, fickle creatures I loved from folklore, who couldn’t lie, despised cold iron, and had a decidedly troubled relationship with gluten products.

And yet, this book didn’t exist. If I wanted to read it, I’d have to write it myself.

With that, I tumbled down a strange, yeasty rabbit hole. The shower was still running, but I was miles away. If fairies couldn’t bake bread, I wondered, did they simply magic their own bread into existence or did they have to do without? What if they relied on humankind for bread? And what if it wasn’t just bread they couldn’t make—weren’t sewing, carpentry, blacksmithing, and painting equally human pursuits, a knitting needle and an anvil and a paint brush imbued with the same properties as the hearth? (At this point, I was frenziedly attempting to shampoo my hair with conditioner.) What if fairies had to trade with humans for all their material goods, in the process satisfying some desperate craving for mortal craft?

The possibility electrified me like a lightning strike. I instantly knew this idea was the beating heart of a potential novel. I got out of the shower and, still dripping wet, I began to write.

I found my story in Whimsy, an isolated village where craftspeople traded gowns and portraits, pastries and fine cheeses to the uncanny lords and ladies of the forest: the fair folk, who offered humans treacherous enchantments in exchange for Craft. The book unfolded as a tale about the relationship between creativity and immortality, the idea that something—or someone—can only possess meaning through change. Without the ability to Craft, the fair folk are empty creatures, motivated by the longing to surround themselves with human innovation in the hope and terror that it might make them feel. And like bread’s contradictory role in folklore, Craft is not only desirous, but perilous to them: if the fair folk so much as put a pen to paper themselves, they will crumble to dust.

As an author, the question I receive most often is “What inspired your book?” The answer is, truthfully, everything—every life experience I’ve ever had, every piece of media I’ve ever consumed, thrown into a pot and melted down until most of the ingredients are no longer identifiable. But since that isn’t a particularly satisfying thing to hear, I’m grateful that in this case I do have at least one specific source of inspiration, and that it (my sincere apologies) makes for a strange and breadful tale.